Seven years ago, as Toronto author Alison Pick began researching and writing what would become her prize-winning novel Far to Go, she realized that the seeds of two different projects — one a fictional manuscript, the other a closely allied memoir — were struggling for dominance within her mind.

Seven years ago, as Toronto author Alison Pick began researching and writing what would become her prize-winning novel Far to Go, she realized that the seeds of two different projects — one a fictional manuscript, the other a closely allied memoir — were struggling for dominance within her mind.

Giving priority to the novel, she spent three years immersed in its details, motivated by a deeply personal connection to the fictional characters she had willed into being. Published in 2010, Far to Go is a Holocaust story set in the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939 around the time of the infamous Munich Agreement, just as the Nazis were preparing to deport the region’s Jews.

A large part of her creative inspiration for the novel came from the fact that Pick, raised in an ostensibly Christian family in Kitchener, Ont., was actually the daughter of a Jewish father whose parents never told him of his birth religion, nor that his grandparents and many relatives had perished in the Holocaust. These family secrets, which Pick first stumbled upon at about the age of 11, gained immeasurable significance for her over the years.

While researching the novel, Pick immersed herself in the history of Czech Jewry in the Holocaust era and about Judaism in general, to which she brought a growing fascination. “It felt extremely resonant in a way that Christianity never had,” she told me during a recent interview in her publisher’s office in downtown Toronto. “I sort of had the experience that I was recognizing what I already was.” After years of courses and study, she underwent a conversion and reclaimed “our family’s lost Judaism.”

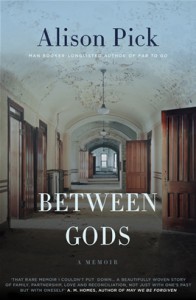

Pick eventually completed the memoir, which Doubleday Canada recently published as Between Gods. It is a personable and surprisingly dramatic telling of the author’s transformation and spiritual journey “back” to her Jewish roots, thankfully with little trace of any dry theological discussions.

Pick eventually completed the memoir, which Doubleday Canada recently published as Between Gods. It is a personable and surprisingly dramatic telling of the author’s transformation and spiritual journey “back” to her Jewish roots, thankfully with little trace of any dry theological discussions.

At the centre of the narrative is a walk down the aisle as Pick marries her non-Jewish partner, Degan; on a parallel track in her life, she makes a serious commitment to Judaism and is immersed in the mikveh. (The beit din struggles with the issue of converting only one partner in a mixed relationship, but ultimately sets a precedent in Pick’s case: later, when the pressure is off, Degan voluntarily opts to become Jewish as well.)

Death and life are both abundantly represented in this tale. The former takes the shape of Pick’s sorrowed meditations on relatives lost in the Holocaust as well as the unfathomably painful experience of a miscarriage. That there is also the blessing of new life in this tale seems a reflection of Judaism’s focus, as Pick puts it, on forgiveness and redemption rather than on original sin.

As a secondary theme, Between Gods deals with the effects of Nazi persecution on future generations within the author’s family; she links a past generation’s trauma of the Holocaust to her own crippling depression.

Pick’s paternal grandparents, escaped Europe and came to Canada in 1940, settling in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Born in Canada in 1944, her father did not suspect he was Jewish until he visited Prague in his early twenties and a tour guide told him he had a Jewish surname. (In more recent times, he’s been overwhelmingly supportive of Pick’s move back to Judaism.)

As a preteen, Pick overheard a pregnant exchange between her mother and aunt at a family Christmas party in which they agreed that “our girls aren’t technically Jewish” because their mothers weren’t Jewish, even though their fathers were. This conversation was supposed to sail over little Alison’s head, but didn’t.

“I remember this moment as if it were in a cartoon: a little light bulb appearing in the air above my head, and the sound effect, the clear ting of a bell,” she writes. “My brain was working fast, trying to process this information. Who did they mean by ‘our girls’? They meant my cousins. They meant my sister. They meant me.

“I put my half-eaten marzipan back on the plate. I was not Jewish because my mother was not Jewish. But my father, the implication seemed to be . . .”

In Far to Go, Pick empathically re-created the world of Czech Jewry as her grandparents and great-grandparents would have known it. The story focuses on the Bauers, a secular Jewish family who, like most of their counterparts, proudly consider themselves full and assimilated Czech citizens. As the unstoppable Nazi juggernaut progresses, they manage to place their young son onto a kindertransport to England but are unable to save themselves from being deported to a death camp.

Longlisted for the coveted Mann Booker prize, Far to Go became Pick’s breakthrough book, catapulting her name as far afield as London, Prague, Istanbul and China — all places she has visited on promotional tours. It has also won various awards, including the Canadian Jewish Book Award for fiction, and been translated into a handful of European languages. Film rights have been sold to a Toronto film production company that has reportedly engaged talented Canadian playwright Hannah Moskovitch as one of the screenwriters.

Pick says that during her book-signing tours, people often tell her their own family Holocaust stories. “It’s just nice to have people tell me they really loved the book and that it resonated with them,” she says. “And the nicest thing is when people say it made them cry. That always makes me feel good. You know you’ve succeeded as a writer if they cry.”

Meanwhile, Pick has attempted to explain the nuances of her family’s Jewishness to her young daughter, now five years old. “One day I tried to explain to her that her Saba was Jewish but her Granny wasn’t, and that I chose to be Jewish. She got very impatient with me and said, ‘I’m Jewish!’ She just experiences it as something that’s not complicated. She takes it for granted.”

Reading Between Gods somehow put me in mind of Robert Frost’s famous poem about two roads diverging in a yellow woods, as well as Reb Nachman of Bratslav’s famous saying, “All the world is a narrow bridge.” How awesome that Pick’s fateful treading of a spiritual path to Judaism ultimately has the power to transform future generations and so much more than herself. ♦