From the Canadian Jewish News, February 2015

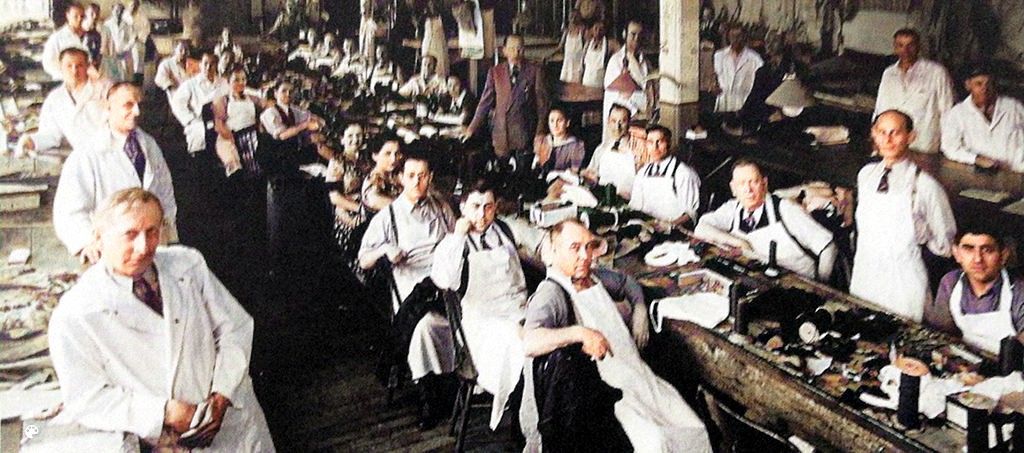

In late 1947 and early 1948, representatives of the Canadian garment industry organized what became known as the Tailor Project, a plan to select more than 2,200 skilled tailors from the Displaced Person camps of Europe and give them jobs and housing in Canada.

In late 1947 and early 1948, representatives of the Canadian garment industry organized what became known as the Tailor Project, a plan to select more than 2,200 skilled tailors from the Displaced Person camps of Europe and give them jobs and housing in Canada.

The Tailor Project had been based on similar schemes that had alleviated labour shortages in the logging and mining industries. Canadian Jewish Congress, eager to rescue Holocaust survivors from the terrible limbo of DP camps, knew the government would approve a plan to bring in skilled workers to fill a similar shortage in the garment trades.

Congress officials, recognizing that the plan had to come from the industry itself, wisely provided guidance from behind the scenes. “Congress was not an employer of labour and could not act as a spokesman,” the late Max Enkin, a key player in the Tailor Project, explained in a 1986 recorded interview.

Hundreds of tailoring firms in Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver were canvassed and many agreed to hire DP workers on 12-month contracts. W. Krangle and Co. Ltd. of King Street sought 5 persons “experienced in the sewing of men’s trousers”; Brill Shirt & Neckwear Ltd. of Richmond Street wanted 30 “operators on men’s fine shirts”; Coppley Noyes & Randall of Hamilton sought 10 workers; Superior Converters Ltd. of Fraser Avenue requested 25; Master-Bilt Clothes Ltd. of Spadina Avenue sought 5; Nash Tailors Ltd. of College Street wanted 8; Ontario Boys Wear Ltd. of Richmond Street W. wanted 7; and so on.

Provided they had the requisite tailoring skills, both single and married DPs were eligible to come to Canada, but couples with more than two children and one-parent families were excluded by government fiat. In their book None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948, Irving Abella and Harold Troper tell the story of a widow from Romania with a young son who, despite her “tearful pleading,” had to be rejected. However, the selection team found a single Romanian man and arranged a quick marriage; the two, sleeping in separate berths aboard ship, came to Canada with the child in February 1948 and were later divorced.

The Canadian Overseas Garment Commission, the industry’s coordinating body, had to ensure proper housing for the thousands of expected workers. Enkin, who went to Europe as part of the selection team, telephoned from Vienna to emphasize the importance of providing accommodation. “If there are insuperable difficulties and insoluble problems it is obvious that Mr. [Arthur] MacNamara [Deputy Minister of Labour] would want to terminate the project,” he explained, adding that “the situation of these people in the camps is appalling — they must be rescued.” Many people and organizations offered accommodation, including the Hebrew National Association (Folks Farein) on Cecil Street, which provided placements for 18 people.

Unfortunately, the government applied a quota to the project at the eleventh hour, insisting that no more than 50 per cent of the chosen tailors could be Jewish. Although Enkin and his colleagues felt they had no choice but to comply, the quota was apparently eased when the tailors began to arrive in stages.

In the four Canadian cities in which it operated, the Tailor Project unfolded with the precision of a military operation. In Toronto, each newly-arrived group was met at Union Station and transported in Red Cross station wagons to the Labour Lyceum on Spadina Avenue where the new arrivals were welcomed, given breakfast, registered, then driven by car to the homes and apartments allocated to them.

“When a D.P. commences work in your establishment, he has no means of sustenance,” employees were advised. “Each manufacturer is, therefore, requested to advance to each D.P. the sum of $25.00 for married men and $15.00 for single men. We would suggest that the advances be deducted weekly in the smallest possible amounts, to enable the Tailor to retain his maximum pay until such time as he may become well-established.”

The Tailor Project became the template for the Furrier Project that followed and the model for bringing the Vietnamese “boat people” to Canada about 1980, Enkin said. The project also spurred the formation in 1947 of the Jewish Vocational Service of Toronto, the original purpose of which was to help survivors of the Second World War find employment; Enkin was its founding chairperson.

◊ This is the second in a series of articles to appear in the Canadian Jewish News, funded by the J. B. & Dora Salsberg Fund of the Jewish Foundation, about Toronto’s Jewish institutions and history as reflected in the resources of the Ontario Jewish Archives Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre.