TORONTO POLICEMEN ARE MODELS OF POLITENESS

Their Clubs Are Merely Ornamental, But They Manage to Enforce the Laws – How a Police Court Hearing is Conducted – The Finest are the Guides, Counselors and Friends of Our Canadian Neighbors – Not Like Pittsburgh.

by Henry Jones Ford

Pittsburgh Gazette, July 12, 1903

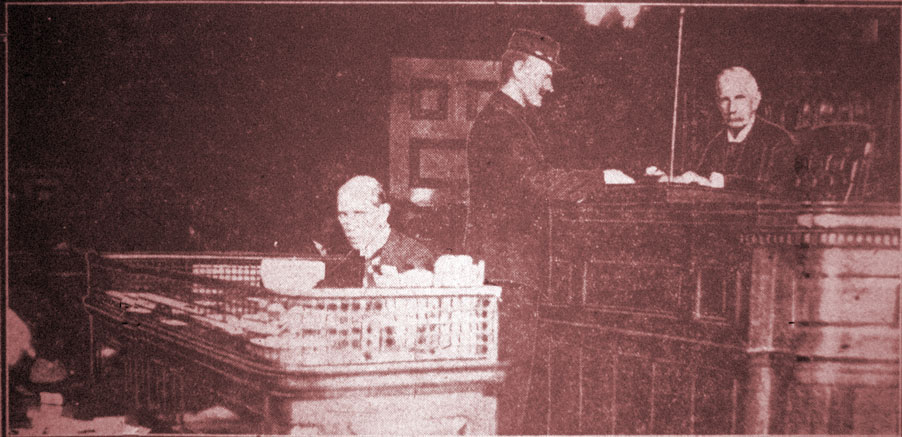

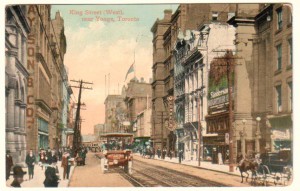

Above: Newpaper photo from Colonel George Denison’s police court, Toronto 1920

Toronto, July 9, 1903 — An advertising performance was going on in a shop window, attracting a crowd. On the sidewalk stood a big man of military dress and bearing, and if anyone loitered he would say in a cheery tone, “Move on please, the sidewalk must be kept clear.” People obeyed him without demur, and the sidewalk was kept clear, although people lined up on the curb anxious to see the show. Everybody seemed good humoured toward the big man, whose manor was extremely civil as well as authoritative. He would correct the curb line with: “A little too far out, there. Step back, please, thank you.” Everything went on in a spirit of mutual accommodation and the passage was kept constantly open for people passing along the street.

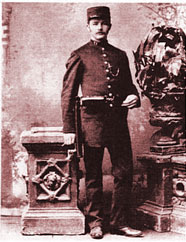

The big man was a Toronto constable; what we call the police force is there the constabulary. Our policemen wear a black coat and trousers that would be like the ordinary citizens’ dress were it not for the brass buttons and the metal edge on the coat front. The Toronto constable wears a tunic, fitting close to the waist, and coming down over the hips with a flare that gives a spread to the skirts. His trousers have a red boarded stripe. His helmet is not a round fit like that of our police, but is a constable?-like affair of military look with deep visors front and back. A strap hangs down in front, barely reaching the chin, so that it really has nothing to do with holding the helmet in place. The Toronto constable does not carry his baton dangling from his hand, as do our policemen, but wears it as a sword in a leather sheath, suspended from his belt, so that his hands are free. In this dress he marches along, trim and erect, like a soldier on parade.

Everybody’s Friend and Helper

I was struck by the differences from our police style, not only in dress and bearing, but also in manner. The Toronto constable seems to be universal helper and everybody’s friend. It is taken as a matter of course that he will be civil and agreeable, and in any sort of trouble or perplexity people instinctively turn to the constable for assistance. If a person has a grievance against anyone the constable is told about the matter and he tells what to do; if the offence is actionable and the affair can’t be settled by friendly recommendation, a summons is issued and the case is settled in the county court. One police court and one county court between them attend to all the business that with us occupies five police magistrates, 38 aldermen and 38 constables. Most of the business that supplies fees to our aldermen and constables are settled out of court in Toronto without expense to anybody. If a person sustains trespass or annoyance from a neighbour, the instruction of the constable usually settles the matter. “If you don’t, I must summons you, you know,” is an argument that rarely fails. Anyone that easily want to go to law can, of course, get all the law he desires, but the spats and quarrels which with us furnish grist to the alderman’s mill are in Toronto usually settled by the constable. But while there is no petty magistracy living in the community, singularly enough coroners are so abundant that there are several in every ward. When I expressed my surprise at this, I was met by surprise that the arrangement should be considered remarkable. “You see, it provides that there shall be always some coroner in convenient reach of the constable” was regarded as ample explanation. The coroners are always physicians and receive no salary, but if an inquest is required there are fees.

Besides his function as guide, philosopher and friend to the community, the Toronto constable has various duties to perform not included in the ordinary work of our policemen. The constabulary attend to the city license fees and last year collected $33,786.60. They enforce the liquor laws and prosecute violations. The sale of liquor stops short at 7 o’clock Saturday night and does not begin again until Monday. And there is no humbug about it. The law is rigidly enforced, and Toronto is tight and dry on Sunday. Last year there were 46 liquor prosecutions, but the offenses were unusual and all hands agree that there is no opportunity for any habitual sale of liquor contrary to law. The constabulary investigate absence from school, and last year attended to 5,618 such cases, returning 5,230 children to their lessons. The department carries on an ambulance service, and 247 members of the force have certificates of ability to render first aid to the injured: They note, report and prosecute any violation of city ordinances. I saw no encumbrance of roadway or sidewalks or litter in the streets of Toronto. The constable appears to be an all-around public servant, and is so urbane and considerate in every capacity that he appears to be in favor wherever he goes.

I noticed that the flap of the leather sheath containing the constable’s baton was invariably buttoned down, so that the baton seemed more for ornament than use. I mentioned this to Col. Grasett, the chief constable, and he remarked: “Yes, it might as well be done away with, as it is never used.”

“How, then do your men protect themselves when they go up against a gang?” I asked.

“Oh, the day force never have any trouble of that kind, but the night force carry revolvers. As a rule there is no disposition to resist the constabulary. People know that they can’t do that, and that they would incur very serious penalties, if they were to try it. In the first place, the chances are that anyone attacking a constable would get the worst of it at once. You may have noticed that they are big and strong. And, then the magistrates would be very severe on any offender convicted of assaulting a constable.”

Completely Out of Politics

The build of the average Toronto constable is certainly what we should call husky. The regulations require a minimum height of 5 feet 10 inches and six-footers abound on the force. One of them is 6 feet 5-1/2 inches tall, with proportionate muscular development. The men must pass a strict physical examination on joining the force, and get regular gymnastic training. From the look of the average citizenship of Toronto, I should think that there would be trouble in getting together such a collection of stalwart men if the force were recruited solely from townsmen. There is however, no requirement as to citizenship. The force is recruited like a military force, any British subject being an eligible applicant. His name, country of birth, age, height, former service and date of appointment appear on the roll, also whether married or single and, curiously enough, his religious belief. On joining they pledge themselves not to attend any political meetings or to engage in political discussion or attend the meetings of secret societies. The new recruit receives $1.35 a day, less 5 percent, which goes to the benefit fund. Length of service as an ordinary constable will gradually advance him to the maximum of $2 a day. In addition there is a good conduct pay of 10 cents a day to be earned for every five years of unblemished record. We pay our police $3 a day but living is much cheaper in Toronto than in Pittsburgh. The chief receives $3,000 a year, the same as with us. All fees earned by the force must be turned into the benefit fund. In case of illness only half pay is allowed, the other half being turned into the benefit fund, which is an emergency provision for the force and a source of pension allowance upon superannuation.

The force is so completely out of politics that I found that Col. Grasett was not well posted on the subject. His attitude was very much like that of our regular army officers, who hold aloof from party politics, and his bearing and manner was that of the office and gentleman. His official title is chief constable corresponding to our chief of police and his military title comes from the fact that he was formerly lieutenant colonel of the Prince of Wales Leinster regiment. “I do not myself vote in the mayoralty election,” he remarked, “because the mayor is a police commissioner. I know very little about the political opinions of any member of the force.”

“But how do you keep politics out of the force?” I asked.

“There is no trouble about it at all. Why should they meddle with what does not concern them? For a constable to engage in party electioneering is sufficient cause for dismissal.”

“Do not changes take place in the force from time to time?”

“No more than are required in the enforcement of discipline after trial of charges. Positions are permanent during good behavior.”

Length of service is characteristic of the Toronto police force. Col. Grasett has held his position for 17 years, but he considers himself rather young in the service, as his deputy has been on the force 42 years, and before joining was a member of the Royal Irish constabulary. Four of the six police captains have been on the force over 30 years. The junior captain in length of service has been on the force 20 years and spent 14 years in the military or police service elsewhere before joining the Toronto force. The chief of detectives has served 28 years. One of the sergeants has served 34 years; another 33 years. The majority of those in positions of command are of British nativity and had police or military experience in England. One sergeant, who has been for 31 years on the force, had previous service of four years in the royal navy and three and a half years on the London police force.

I attended a hearing at the police court. The prisoners from all the six police stations are brought to the court. The arrangements and procedure were very different from those customary in Pittsburgh, and I kept contrasting the scene before me with that presented at the hearing in our Central police station. There a railing extends in front of the magistrate’s desk and prisoners are brought behind the railing and stand against the desk across which the magistrate talks to them. The rest of the room is open to the casual crowd. It is impossible to hear much of what is going on, as the magistrate has only the width of his desk between him and the prisoner, and question and answer go on in a conversational tone and in an unceremonious way. There is a reporter’s desk alongside of the magistrate’s desk, so that the reporters can follow the proceedings, but they are mostly dumb show to the crowd lounging in the room.

The Toronto police court is a clean, handsome, spacious judicial chamber, rather more ornate in its appointments than our court rooms in the county building and except that all cases are tried without a jury proceedings go on just as in the higher courts. A crown counsel is present to represent the state, and the magistrate sits as a judge, and does not himself examine prisoners and witnesses as do our police magistrates. A constable known as staff inspector has a desk on a raised platform in line with the magistrate’s desk, but detached and much lower. Along the side of the room on a raised platform is a long desk for the press capable of accommodating about a dozen reporters who are placed where they can see and hear everything. The prisoner’s dock is in the rear of the room and is reached by a stairway from rooms below. There are rows of benches for the public and it is easy to hear everything said. A peculiarity which at once strikes a visitor is that the constables present all wear their helmets. A constable never uncovers to anybody. That is a privilege conferred by law. Their erect military figures were a striking feature of the scene.

How Cases are Tried

There was a rapid dispatch of business. “You are accused of such an offence,” the magistrate would say, mentioning the charge. “Are you guilty or not guilty?” Most of the prisoners pleaded guilty. Then the next question would be “Have you been here before?” If the prisoner made a wrong statement, the staff inspector would promptly contradict him and call out the police record of previous arrest. This to me was rather an amusing feature of the proceedings. The staff inspector sat with his hat on and his records before him and would cut in at once in a loud voice whenever a statement was made contrary to the police records.

When the offence charged was of such character that the accused had a right to a jury trial, the magistrate would say: “You are accused of (mentioning the charge); will you be tried now or do you desire the case to be sent to a court of competent jurisdiction?” One such case was that of a respectable-looking woman, who seemed much out of place in a prisoner’s dock. When the question was put to her she appeared to be confused and did not answer. The magistrate immediately continued, “or do you desire time to consult your friends?” She hesitated and then pleaded guilty. She was a servant and the charge was the theft of a ring. “Your worship,” said a constable, “she has had a good character.”

“Case remanded for three days,” said the magistrate. I was told that at the expiration of the time she would be let go, as the ring had been returned.

The magistrate has a regular formula of address for every case, and every prisoner is apprised of his legal rights. If the plea is not guilty, the crown counsel tried the case, and proceedings go on much as in our criminal court except that there is no jury and the magistrate finds both verdict and sentence. In most cases a plea of guilty was entered and the usual sentence was $1 and costs or 30 days’ imprisonment. All the fines imposed seemed to be lighter than is customary with us for like offences, while the alternative penalty of imprisonment was heavier. At any rate the system affords protection to the community. There was no case of homicide in 1902, and but one in 1901. There were only 25 cases of burglary and 20 cases of highway robbery in 1902 involving a total money value of $705. Stealing of bicycles is the most frequent sort of theft, but of 1,362 reported last year as lost or stolen, 1,166 were recovered by the constables and restored to the owners. During the year property valued at $86,432, by the owners was reported as lost or stolen, of which the constabulary recovered $58,310. The force is 302 strong all ranks included. The entire cost of the department, with all its comprehensive functions, for a city of 250,000 was $232,257.67 during 1902 which was nearly $2,000 less than the amount appropriated for it. The Pittsburgh police force cost the tax-payers in 1902, $578,600.

A police force entirely out of politics, diligent in service of many kinds to the public, and enjoying the respect, good will and confidence of the community — what a remarkable phenomenon! The chief is merely an expert in the discipline and management of the force, not sufficiently interested in municipal politics, as even to vote, much less taking a hand in fixing ward primaries and running the political machine; and as for going into council chamber to get out a member and break a quorum, he would be quite as likely to think of taking a trip to the moon. Such action as this by our superintendent of police Mayor Hays did not think of sufficient importance to investigate. In Toronto for a constable even to talk politics is promptly punished as a breach of discipline. And such things as vice syndicates, or political interference of any kind with the work of the department is unheard of, and is regarded as something inconceivable. And in connection with the police work there is an administration of justice, swift, exact and sure, but impartial and scrupulously respectful of individual rights. Such a thing has been heard of in Pittsburgh as a magistrate turning up at a police station out of hours to hear and release some of his friends run in by the police. It would be impossible here. What a session of court without the presence of the crown counsel, the staff inspector of constabulary, and the regular procedure of justice! That is quite inconceivable.

“The political pull” appears to be unknown in Toronto — nothing doing in the way of ward politicians getting friends out of trouble or softening the case by a private word with the police magistrate.The funny stories which are current in newspaper circles on such subjects at home are not heard here. I could find no trace here of the political class privileges with which we are familiar. All classes stand equally before the law. No matter how popular a liquor saloon a man may keep . . . and no matter how influential a politician he may be in his ward, it doesn’t appear to give a particle of pull on the police or the court. This state of affairs makes it easy for the police to control the social evil. There is no political influence available for running protected houses and resorts, encouraging the display of vice; later on to be followed by wholesale raids at the vicissitudes of politics brings new political interests to the top, keen to display their power and eventually tending to reproduce the old conditions for their own benefit. Here the social evil is repressed and vice kept off the streets without spasmodic raids. The fines collected in cases of this kind amounted last year to $1,427, or about half those collected recently from the raids of a single night in Pittsburgh.

How is it that these people here, under a monarchy, although they govern themselves, are able to fully to accomplish democratic equality? They talk the same language, look and dress just as we do, and are certainly no more capable and intelligent. And they seem to do it so easily. There is no fret about politics, no particular strain or effort, and indeed they do not seem to give the subject the same amount of attention as we do. There are no voters’ civic leagues, municipal leagues, good government clubs or other organizations to hector public officials as to their duties and yet the public business goes on economically and efficiently. The secret must be contained in their system of municipal government, and in succeeding letters I shall give some account of this. ♦

◊ You may also enjoy A Victorian Police Detective in Toronto