◊ Finding the Jewish Shakespeare, The Life and Legacy of Jacob Gordin, by Beth Kaplan, has been newly released in paperback by Syracuse University Press, Spring 2012.

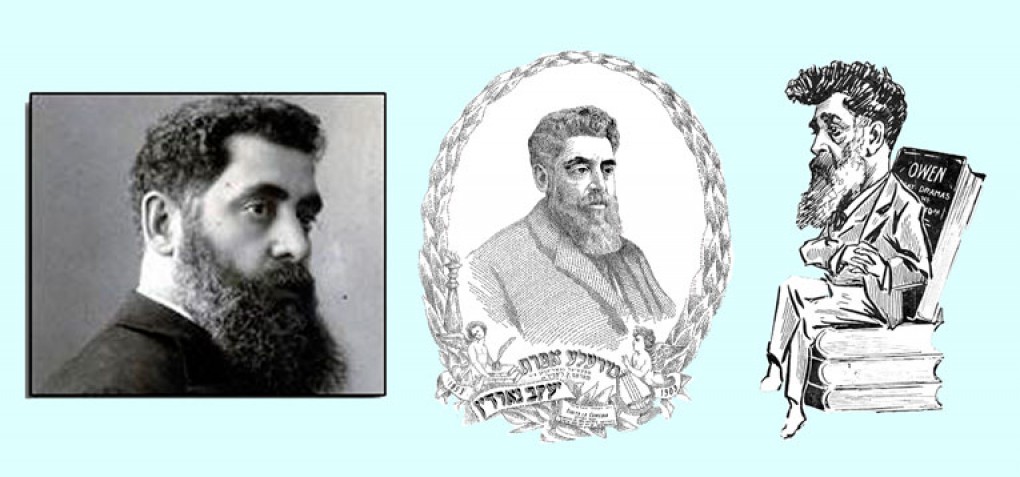

One of the great moments in Yiddish theatre occurred the evening the curtain opened upon actor Jacob Adler in the role of “the Jewish King Lear,” as envisioned by playwright Jacob Gordin in his play of the same name (“Der yiddisher kenig lir”), which premiered on New York’s Lower East Side in 1892.

More than a direct translation of Shakespeare, Gordin’s groundbreaking opus was a fresh interpretation of the story of a patriarch with three daughters who are unkind and disloyal to him. In Gordin’s retelling, the hero is David Moisheles, a Russian-Jewish merchant whose daughters abandon their filial love and duty towards him.

Adler triumphed in the role, which he would reprise until his death, but the production also made Gordin’s reputation as a bold realist and reformer of the Yiddish theatre, and as someone who, as a rival playwright once observed, wrote “roles, not plays.” To a generation of incipient Americans who had left their parents behind in the shtetls of Europe, the play’s theme of parental abandonment rang with a deep and sad resonance.

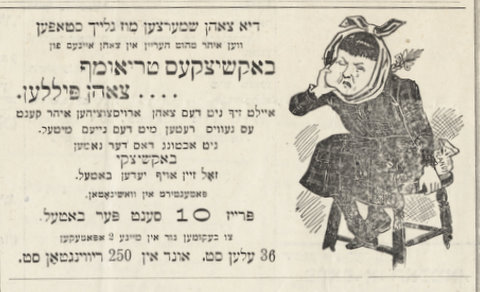

“Gordin’s play had a profound impact on the Lower East Side,” writes Beth Kaplan in Finding the Jewish Shakespeare (Syracuse University Press), her remarkably thorough and insightful biography of the playwright, her legendary great-grandfather. “In one much told story, a distraught playgoer was so swept into the drama that after a tragic scene he ran down the aisle toward the stage, shouting that Adler should leave his heartless daughters and come home with him. Young people, witnessing the degradation of the elderly man, were stricken with remorse about their own parents. It is another famous legend that local bankers knew which nights the play was being performed because early the next morning, youths afflicted with guilt were lined up at the banks, waiting to send money home.”

Ironically, after the play’s first reading, many of the players had prognosticated it would fail because Gordin had removed the cheap effects, cheap laughs and contrived melodrama that were hitherto compulsory elements of the Yiddish stage. “What will I do in that play? Catch flies?” one actor had complained. Further, the tyrannical playwright had insisted that actors give up their time-honoured tradition of adlibbing long flowery speeches to make their parts more meaty. Astonishingly, he wanted them to stick to the script — and the original Yiddish language in which it was written, not the embellished, more elegant “Daytshmerish,” closer to German, that they often preferred.

Embracing the trend towards realism set by Chekhov, Ibsen, Tolstoy and others, Gordin (1853 – 1909) was determined to improve the Yiddish theatre as practiced by Abraham Goldfaden, his illustrious contemporary who had established the first Yiddish theatre in Jassy, Romania in 1876 and had penned a series of crowd-pleasing comedies and satires in a fluffy, romantic vein. As Kaplan points out, the Oxford Companion to Literature defines realism as “a movement devoted to the facts of life, especially if they’re gloomy.” To Gordin, theatrical realism was an essential medicine that modern audiences needed to swallow, whether they liked the taste or not.

Embracing the trend towards realism set by Chekhov, Ibsen, Tolstoy and others, Gordin (1853 – 1909) was determined to improve the Yiddish theatre as practiced by Abraham Goldfaden, his illustrious contemporary who had established the first Yiddish theatre in Jassy, Romania in 1876 and had penned a series of crowd-pleasing comedies and satires in a fluffy, romantic vein. As Kaplan points out, the Oxford Companion to Literature defines realism as “a movement devoted to the facts of life, especially if they’re gloomy.” To Gordin, theatrical realism was an essential medicine that modern audiences needed to swallow, whether they liked the taste or not.

The dark, bearded author of some 80 Yiddish plays, including the classics Mirele Efros (a sort of Yiddish “Queen Lear,” 1897) and Got, Mentsh, un Tayvl (God, Man and Devil — a sort of Yiddish Faust, 1900) was not above delivering stern reproaches to audiences between acts on their need to improve their artistic taste. “My plays, and those of my colleague Ibsen, do not please,” he lectured during the first week of the initially underappreciated Got, Mentsh, un Tayvl, and went on to emphasize that the theatre was a place for instruction, not amusement. “Truth is the teacher, and therefore, I will continue to provide serious plays until you acquire a taste for them.”

“Surely never before had an audience been admonished directly by a playwright, even a smiling one, to change its taste for shallow entertainment and gravitate to him,” Kaplan observes. “Gordin’s speech worked. The play went on to become a success.”

When the playwright’s serious play Elisha (1906) proved an unqualified flop, he was hurt beyond words, and delivered much lighter fare in his next work, The Stranger, which proved a hit. Even so, Gordin was appalled that theatre-goers were regressing back to their old habits, and came out one night and scolded them, Kaplan relates:

“‘I gave you a play, Elisha, and you didn’t like it, though I liked it very much. Now I give you another play — you like it, and I, not at all,’ he said, again surely unique among playwrights in publicly dismissing his own most recent work. ‘Why do you run to see a melodrama like this? What pleases you about it?’” (The players, naturally, were furious with him, especially Jacob Adler, who performed the leading role. “Mr. Gordin, what have you done?” he cried. “You’re killing my success!”)

Kaplan documents Gordin’s long-running public feud with Abraham Cahan, the influential editor of the Daily Jewish Forward, who once observed that Gordin suffered from “critic fever” because he could not tolerate criticism. “Gordin considers himself a fighter because he has a big mouth,” Cahan wrote. “That is his heroism. This tall man with the grey beard, the proud carriage and the coquettish walk is as deathly afraid of the mildest criticism as a baby is afraid of lukewarm water.”

Although Cahan occasionally softened his criticisms with praise, Gordin was terribly wounded by Cahan’s negative judgements and considered him “my principle detractor, because whatever I build, he tears down, because whatever I’ve been doing all my life, he negates. We are working for the sake of the selfsame people. But I want to lead them forward, and he drags them backward through the Forward. I say to them, a man must be upright and defend his principles unequivocally; he teaches them to be politicians. I say, a revolutionary should not be two-faced . . . . He says, you have to keep the [newspaper] circulation in mind. I say, you have to lift the masses up to your level. He says, you have to stoop down to the level of the masses, cater to them, and accommodate yourself to their basest instincts.”

One senses Gordin’s underlying perception of the “low” Jewish masses who need to be educated and elevated, and Cahan’s populist approach by which he gave the people what they wanted and increased his paper’s circulation astronomically in the process. By illuminating such intrinsic ideological and artistic differences, Kaplan helps us understand the Jewish world of more than a century ago and brings a dim milieu to vivid life.

A perceptive biographer with a close psychological grasp of her subject, Kaplan examines her great-grandfather’s legacy within the theatrical context of the times. As to the central question as to whether Gordin’s legacy has lasted, the answer is both yes and no. Yes, because Gordin ushered in a golden age of Yiddish theatre with his most popular work, Mirele Efros, which became a “dependable warhorse for legions of actresses, most notably the indomitable Esther Kaminska,” and which is still performed around the world in a multitude of languages.

“What has guaranteed the longevity of Mirele Efros when so many other Gordin plays vanished instantly?” she asks. “The writer takes the bones of Shakespeare’s Lear . . . but sets it solidly in the Russian-Jewish merchant class of his own background. Like Chekhov in The Cherry Orchard, Gordin demonstrates the end of an old-fashioned, cultured, privileged way of life, and the beginning, for better or worse, of a new way.”

On the other hand, Gordin lived to lament the recidivism by which public taste reverted back to the artless melodrama known as “shund,” and suffered financially when star-managers and producers showed reluctance to take on a new Gordin work, “which brought with it the burden of controversial issues, large casts, and the wrath of the Forward and the Daily Page.” Although upon his death his portrait appeared in every Yiddish theatre and he was honoured in lugubrious speeches as a shining patriarch of the Yiddish stage, his works quickly fell out of fashion, and most remain obscure today.

With this wonderful and meticulously researched book, Kaplan — a Torontonian who teaches creative writing at Ryerson University — has done much to revitalize Gordin’s memory. Part of the book’s charm is her own vital link with its subject as a mysterious ancestor whose reputation had fallen into curious disdain, even among family members. (The book is partly about her journey to “find” what he was all about.) Although Finding the Jewish Shakespeare does not convince us that Gordin deserves the epithet of “Jewish Shakespeare,” it easily demonstrates that he has found the biographer he deserves, and shall certainly find no better. ♦

© 2007