From the Canadian Jewish News, April 2015

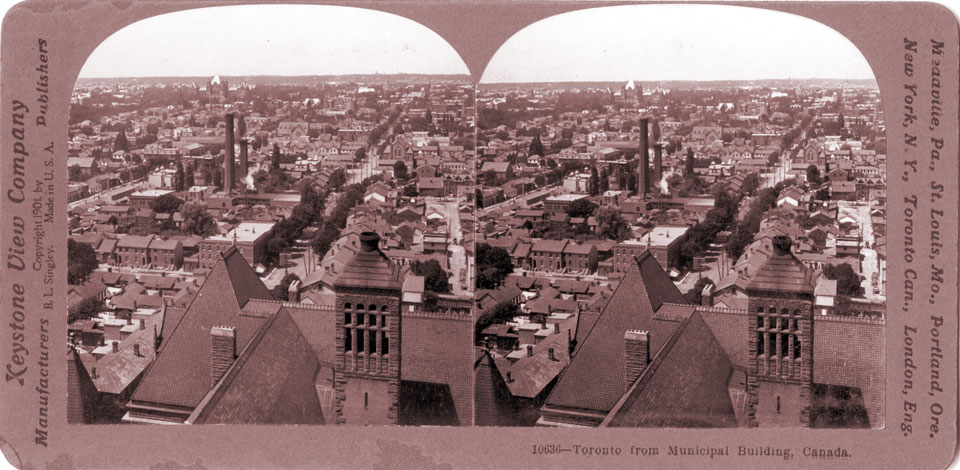

Having recently marked its 25th anniversary, the organization Jews for Judaism continues to counter the activities of missionary groups in Toronto that deceptively target Jews for conversion. However, Christian missions to the Jews are certainly nothing new in this city. In the era before the First World War, a time when the city’s Jewish community was burgeoning with new arrivals, the words of one particular missionary, Reverend Shabetai Benjamin Rohold, sparked a riot in the Ward, the city’s principal Jewish district.

Having recently marked its 25th anniversary, the organization Jews for Judaism continues to counter the activities of missionary groups in Toronto that deceptively target Jews for conversion. However, Christian missions to the Jews are certainly nothing new in this city. In the era before the First World War, a time when the city’s Jewish community was burgeoning with new arrivals, the words of one particular missionary, Reverend Shabetai Benjamin Rohold, sparked a riot in the Ward, the city’s principal Jewish district.

A yeshiva-educated Jew who had converted, Rohold was the son of the Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem. He had arrived here in 1908 to head the Presbyterian Church’s proposed Mission to the Jews, having run a similar mission in Glasgow for years.

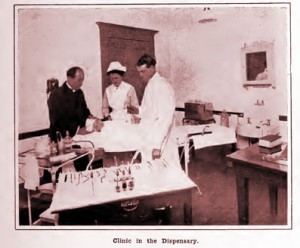

Rohold spent a month visited Jewish homes, shops, synagogues and institutions. Then, using the generous funding designated by the church, he opened a Mission to the Jews on the southwest corner of Bay (Teraulay) and Elm Streets. It provided a free medical dispensary with a trained nurse; a night school with English classes; a nursery, reading room, employment service, boys’ club, childrens’ choirs and sewing classes. It also offered gospel services, Bible classes, and prayer meetings with free Sunday morning breakfasts.

Rohold spent a month visited Jewish homes, shops, synagogues and institutions. Then, using the generous funding designated by the church, he opened a Mission to the Jews on the southwest corner of Bay (Teraulay) and Elm Streets. It provided a free medical dispensary with a trained nurse; a night school with English classes; a nursery, reading room, employment service, boys’ club, childrens’ choirs and sewing classes. It also offered gospel services, Bible classes, and prayer meetings with free Sunday morning breakfasts.

Although attendance was high, conversions were few. While the second annual Seekers After Truth Society supper attracted a mixed audience of some 200 Hebrews and Christians (probably the latter in the majority), in its first two years the Mission had converted only six women and two men (by their own probably exaggerated estimates). Still, when the Teraulay Street premises became overcrowded, the Church built a new and much larger Mission at Elm and Elizabeth. The new premises even boasted a gymnasium and athletic rooms.

No question that the Mission helped many a Jewish family in desperate straits. With excellent knowledge of both Hebrew and Yiddish, Rohold personally took newly-arrived Jewish men seeking employment to various businesses where he had friends, often finding them jobs.

The actions of Rohold and other local missionaries drew a strong counter-reaction from the Jewish community. Members of the Jewish community launched a free medical dispensary, a rabbi opened an anti-missionary headquarters near the Presbyterian Mission, and plans sprouted for a Jewish athletic club.

There is no question that the missionaries had become a major irritant. One stationed himself daily outside the home of Rabbi Yosef Weinreb until the latter attained an injunction from City Hall. Another callously remarked to the press that Jewish homes were just like saloons on Sundays for the amount of liquor consumed, prompting a flurry of angry letters to the editor. In response to complaints that Rohold was proselytizing schoolchildren, he was barred from the grounds of the local Elizabeth Street and McCaul Street schools. Some candidates for municipal office had even promised the Jews that the missionaries would be put off the streets.

There is no question that the missionaries had become a major irritant. One stationed himself daily outside the home of Rabbi Yosef Weinreb until the latter attained an injunction from City Hall. Another callously remarked to the press that Jewish homes were just like saloons on Sundays for the amount of liquor consumed, prompting a flurry of angry letters to the editor. In response to complaints that Rohold was proselytizing schoolchildren, he was barred from the grounds of the local Elizabeth Street and McCaul Street schools. Some candidates for municipal office had even promised the Jews that the missionaries would be put off the streets.

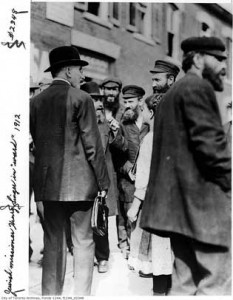

The tension seemed to boil over on the evening of Sunday June 18, 1911, otherwise a pleasant summer evening with the sidewalks filled with people. According to newspaper reports, three speakers — a Zionist, a socialist, and a missionary — had stationed themselves at various corners of the intersection at Dundas and Elizabeth streets.

When someone began translating the missionary’s anti-Jewish slurs into Yiddish, the crowd became agitated. According to reports, people began throwing things and a melee broke out; soon more than a thousand people jammed the intersection. Although a battalion of police officers came running from a nearby police station with their batons at the ready, the riot persisted for three hours and resulted in numerous injuries and arrests.

Over the next few days the newspapers carried various articles and letters in which each side blamed the other. Rohold asserted that while his religious faith obliged him to target the Jews, no one was obliged to listen to him. Despite the dramatic confrontation, missionary activities continued as before.

Rohold, who left for Jerusalem in 1920, had been only one of several formerly Jewish missionaries in Toronto in that era. Another was Morris Zeidman, who founded the Scott Mission — but that’s another story. ♦