From the Toronto Star Weekly, August 26 1911

From the Toronto Star Weekly, August 26 1911

Enterprise of the Household Economic Association Has Achieved Wonderful Results—Little Ones so Frail They Had to Be Carried on Pillows Have Been Bolstered

Up Into Strength—Certified Milk Sold for Eight Cents a Quart, the Society Paying Difference Between Cost and Selling Price — Three Depots in Active Operation.

In the vestibule of a Queen street church nearly a dozen children are gathered, a few of them carrying net shopping bags, the rest paper parcels. The presiding genius is a woman, who, from a zinc covered table is dispensing half-pint bottles of milk – certified milk if you please – cool and fresh from its bed of ice.

“Me next.” cries one little boy, holding up his bottle.

No, please give me next.” says a little girl. Others too, plead for first place. But calmly the presiding genius goes on giving out the bottles, as nearly in turn as she can, although one or two adults in line join the rapidly diminishing group.

“Is baby better to-day?” the P.G. asked little Mary, carefully wrapping up the two bottles in a newspaper for the child.

Little Mary says baby is creeping all over, and much better, and gives other cheery details.

“He was like a little skeleton when he first began getting this milk,” she explains to the visitor sitting to one side. “They had to carry him on a pillow he was that thin.”

Two bottles go to the next boy, and the next carries away four.

“There are as good as two babies in that family, for the oldest is only fifteen months and the other two.”

Two Cents for Half Pint.

Each little customer hands in his or her two cents for the half-pint.

“Please, my money’s in the bottle,” says a little chap, not much more than a baby himself, when he gets his parcel.

Then the P.G. looks over the empty bottles and discovers the missing, germ-laden four cents, and cheerily dispatches the little messenger.

Mothers there are, too, who gladly carry baby and bottles both half a dozen blocks for the sake of milk.

A grandmother comes next and tells of the little new baby whose mother is sick, and cannot nurse and the P.G. gives directions for how much boiled and cooled water must be added to the top cream. The supply of booklets with directions usually kept on hand is exhausted.

An Oil Bath Daily.

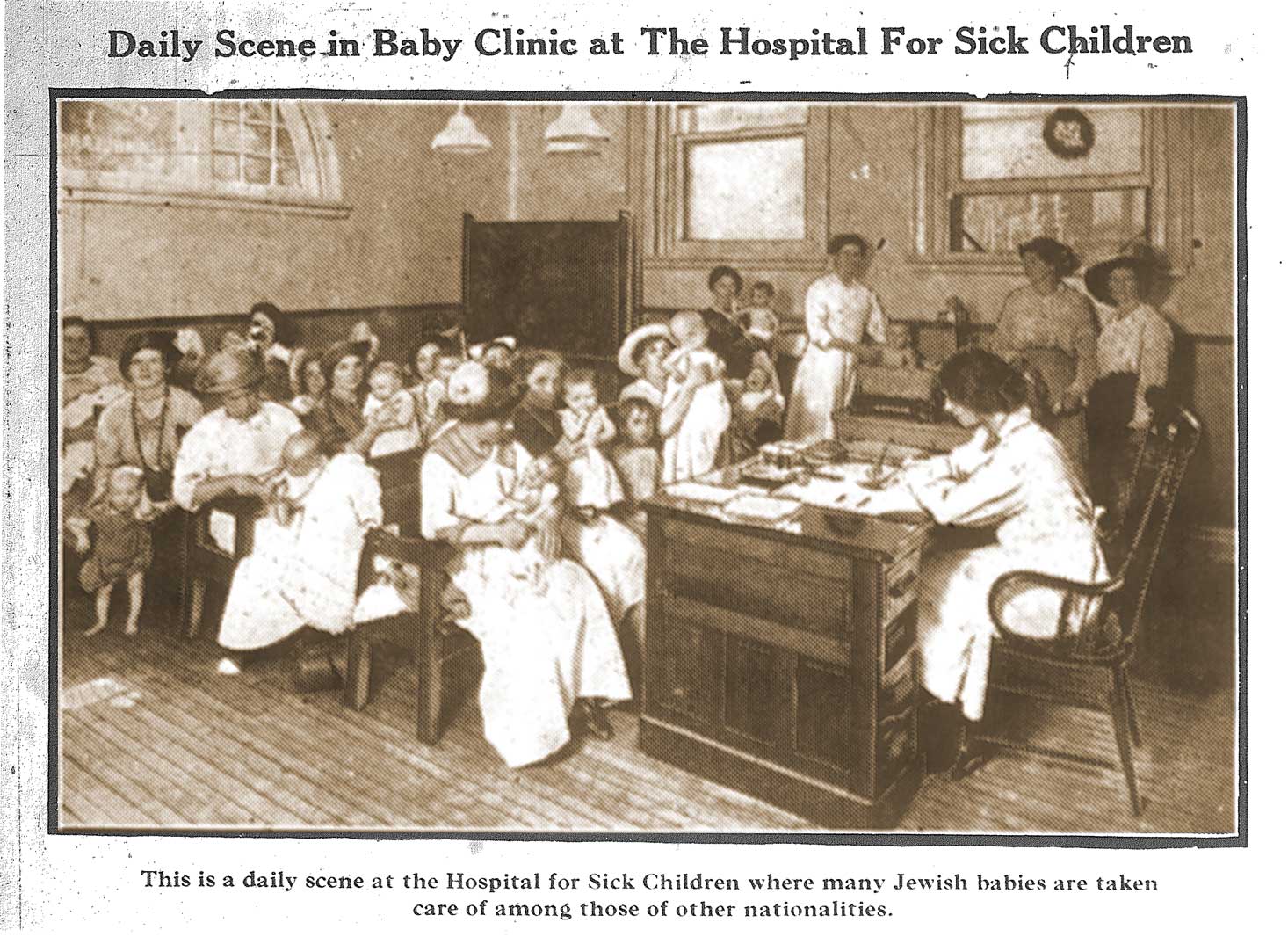

Another mother is advised to give her emaciated baby an oil bath daily, while another is told to take her sick infant to the free clinic at the Sick Children’s Hospital.

Next comes a man, who on his round of work, stops to get four bottles for “the missus,” and tells how well the twins are getting on, and how many teeth they have between them. Don’t you suppose he is prouder of those teeth than if he was a millionaire? Millionaires probably are not so intimately acquainted with what goes on in the nursery.

Then comes a forlorn little woman, carrying her baby. It is a story of ill-luck and perhaps bad management, but anyway, the family is newly arrived in the city, and there has been next to nothing to eat for a couple of days.

“I’m hungry enough to eat the bottle,” says the mother, “but that doesn’t matter; it’s so dreadful for baby.”

The motherly P.G. does not wait for the baby to get home before having his drink, but he must have only a very little at first, for the sides of his little stomach must be nearly glued together, and the mother has directions how often and in what size doses his precious food must be given at first. The fact that there is no money to pay makes no difference. This case brings into play a sideline of work which the P.G. has found inevitable. The story must be looked into.

Life-Preserver for Babies

This milk depot, is the Methodist church, in Queen street west, is one of three, the others being respectively, in the Victor Mission, Queen street east, and Trinity Church, King street east. They were opened two years ago for the summer months by the Household Economic Association, as a life preserver for the babies of the poor.

Talk about race suicide. It is not the number of children that are born, but the number that grow to manhood or womanhood that are the asset of the nation. And how do you suppose a baby is going to exist through the heat of a Toronto summer on milk swarming with deadly bacteria? Poor little mite’s surroundings are all against him, but he has a chance if he can only get decent food.

Here is what a medical authority says: “The majority of babies who die before they are a year old, die from some intestinal trouble, and in nearly every case the cause is improper feeding.”

Wholesome milk is to be had, of course. It always is if you know where to go and can pay the price. But milk fit for a baby to drink costs fifteen to eighteen cents a quart! You might as well tell a woman in the Ward to buy a cow and pasture it in the court where she lives, as to get certified milk!

Society Pays Difference

To the rescue comes the Household Economic Association, seeing that no other body of women is concerning itself about the matter, and arranges to sell certified milk at the rate of eight cents a quart and pay the difference!

To the rescue comes the Household Economic Association, seeing that no other body of women is concerning itself about the matter, and arranges to sell certified milk at the rate of eight cents a quart and pay the difference!

Perhaps you demur that milk is milk, whether anyone certifies to the fact or not.

Quite true, but the point is this: that according to the requirements of the Milk Commission of the Academy of Medicine of this city, milk must come up to a certain standard-it must contain so much solids and so much butter fat, and must be produced and handled under certain wholesome conditions, and must not contain in the hot months more than 10,000 bacteria to the cubic centimetre. When you know that some milk contains millions and hundreds of millions, you realize that such is not a food but a poison, and that the Medical Academy do well to establish a definite standard.

Pasteurized milk Is also sold in the same way at Evangelia House, and a weekly clinic held.

Conserving Human Lives.

We have conservation committees on all national resources: is it not time that the most important resource of all, human life, should come in for its share?

This life-saving movement dates back some years, the first effort having been made in Hamburg, in 1889. Some years after in Paris a milk dispensary for the purpose was established, and in 1893, the first was opened in New York by Nathan Strauss, who spends $100,000 a year in this philanthropy. All through Europe and the States the work has spread, and in Canada, Montreal has followed the lead of Toronto, and Fort William is the last Canadian city to join the ranks. In the towns and in the country it is easier to get good milk, possibly, than in the city, and there are fewer babies to be killed off, but the milk needs looking after there as here.

As to ways and means, it is everybody’s business to save the babies, and the Household Economic Association needs what help it can get. So far there has been no city grant. The expense of the pure milk depots has been met by private contributions sent direct to the Association, or through one of the big dailies for the purpose. Two churches loan their premises, and the committee supervises and finances the work, so that outside the expense of the milk, only two assistants at the depots are paid.

No Winter Supply

“I wish we could get milk all winter.” one mother said, the other day, and the Household Economic echoes the wish, but without much more equipment and expense this would be impossible.

As it is, they have mothered over a hundred babies this summer who, for one reason or another, are dependant on artificial feeding and outside this, and equally important, through the influence of the presiding genius of the depot, and by means of the little pamphlet distributed, each mother has been taught how to feed and take care of the child in a hygienic way. ♦