From AVOTAYNU, 2009

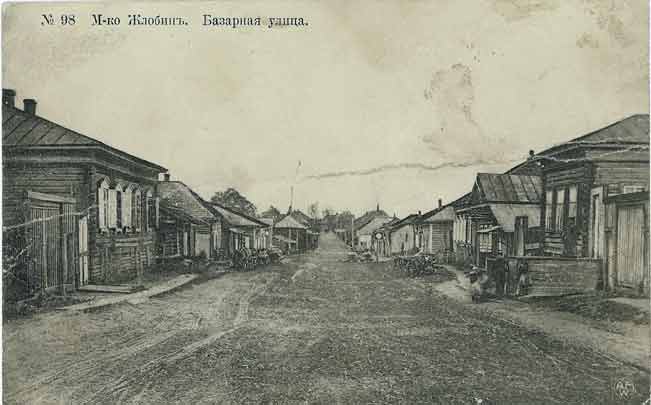

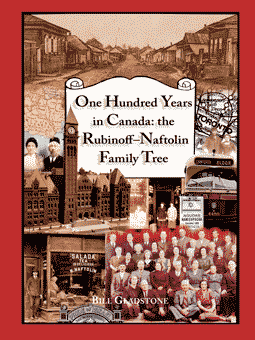

“Zhlobin — Market Street” reads the caption of this rare postcard photograph, circa 1900, of the Belarussian shtetl where my great-grandparents lived before bringing their children to Canada about 1910. The postcard was part of an incredible collection of more than 100 old family-related photos from Russia and Toronto from the 1890s to the 1930s that a distant cousin in Long Island graciously shared with me in 2003, as I was in the final stages of researching my book, One Hundred Years in Canada: the Rubinoff-Naftolin Family Tree (published 2008). The items, which included a 1917 Yiddish postcard from my grandmother, had come from her late mother’s scrapbooks.

Another amazing collection of old family photos surfaced closer to home when another new-found cousin told me of the box she had found under her late father’s bed. It contained many images from Toronto in the WWI era and even a few from the Russia of a century ago. I helped put names to some of the photos and received permission to use them in my book.

These episodes remind me of the importance of going that extra mile and leaving no stone unturned, to borrow two common idiomatic phrases, in the search for stories and artifacts of one’s family history. In each case, a short phone call led to a marvelous addition to my history. I learned many more practical lessons while producing the 384-page book, which turned out to be one of the most rewarding experiences in my life.

One Hundred Years in Canada: the Rubinoff-Naftolin Family Tree traces the arduous journeys of hundreds of my immigrant relatives who came to Toronto from the Russian provinces of Minsk and Moghilev in the early years of the 20th century. All of these cousins are descended from five siblings (and their spouses) who were the children of a single man and wife. Their descendants number in the thousands: they live in Toronto, across Canada and the United States, in Israel, and as far away as Argentina and China.

One Hundred Years in Canada: the Rubinoff-Naftolin Family Tree traces the arduous journeys of hundreds of my immigrant relatives who came to Toronto from the Russian provinces of Minsk and Moghilev in the early years of the 20th century. All of these cousins are descended from five siblings (and their spouses) who were the children of a single man and wife. Their descendants number in the thousands: they live in Toronto, across Canada and the United States, in Israel, and as far away as Argentina and China.

I had been interviewing relatives (some 200 in all) and culling biographical details from many sources for more than 20 years; but over time I had reached the conclusion that the family’s multifaceted saga could never be properly told because there were too many gaps in the story and too much had already slipped from living memory. In genealogy, you either publish your research or it perishes: what other fate awaits your unkempt assortment of files and papers that no one else can understand? However, thanks to the rise of some remarkable internet resources — Jewishgen, Ellis Island, Ancestry, et al — I realized that enough details could be pinned down to allow a fairly thorough genealogical study to be compiled. The family saga was rescued from oblivion.

Using an on-line index of Canadian naturalizations available through Libraries and Archives Canada, I applied for the naturalization papers of at least 60 relatives: these wonderfully detailed papers contain multitudes of stories, clues and revelations. The Toronto Star’s remarkable “Pages of the Past” database produced nearly 500 family-related birth, marriage, death and military notices, news stories, business advertisements and feature articles. (I had previously spent uncounted hours searching reels of microfilm with a much lower rate of return.) Visits to the Ontario Archives and the City of Toronto Archives reaped further riches. As I gradually collated all of these new elements, it became clear that many elusive critical details had surfaced and that no valid excuse remained for not completing and publishing my research as a book.

The journey that family members took from the old world to the new was a central focus of my narrative. “Who left when?” and “Why?” were key questions that I wanted to answer. I wanted to pinpoint the order and itinerary of that shadowy exodus that marked the genesis of our Canadian existence. Another question I had was “Where?” I wanted to know not only where my grandparents were born but also the birthplaces of their many cousins. Besides Zhlobin, the towns include Streshin, Rechitsa, Vasilyevitch, Horval, Holmetz, Davidofka, Turki and Bircha — a sprinkling of towns southeast of Bobruisk, many along the Dnieper River.

Interestingly, many of the new arrivals declared in their papers that they had come from Bobruisk, the provincial capital. In almost all cases, this has proven to be a generalization, much like saying you are from Toronto when you are really from Newmarket, Barrie or another nearby town.

As expected, the mass exodus of my grandparents’ many aunts, uncles and cousins was triggered by the usually-cited factors: pogroms, poverty, war, military draft, political instability. However, six or seven relatives told me stories of a family tragedy that also spurred some relatives to leave. Two teenaged children of my grandfather’s aunt and uncle drowned one spring in the Dnieper River. Afterwards the rabbi told them “Meshone makom, meshone mazel” — “Change your place and you change your luck” — and steamship tickets were purchased.

The first relatives in the extended family began leaving about 1905; between 1907 and 1914, the trickle became a flood. Groups of cousins often traveled together. Most went by train to the Latvian port of Libau, then by ship to Liverpool, where Jewish volunteers offered kosher food, a warehouse to sleep in, and other travelers’ aid. After the grueling ocean crossing, most landed in New York, Halifax or Quebec City. Several attempted to settle in New York and Kingston, Ontario, but almost all eventually arrived — tired, hungry, and frequently penniless — in Toronto, where a thriving Yiddish-speaking community had arisen in the downtown core: a miniature version, complete with tenements, of New York’s Lower East Side.

Strangers in a strange land, the first arrivals assisted those who followed: housed them in their own crowded living quarters, helped them to find jobs, learn English, find living quarters of their own. Awaiting each arrival was an extensive support network called the “mishpocha.”

When my grandparents’ many cousins formed a family society in 1928, their model was the mutual benefit societies, landsmanschaft organizations and similar associations founded by other local Jewish groups of that era. In his 1978 book, Mishpokhe: A Study of New York City Jewish Family Clubs, William E. Mitchell notes that the Jewish penchant to create voluntary associations had been prominent both in Eastern Europe and New York since the early 1800s; it was once said that New York’s Lower East Side “swarms with clubs almost as much as it swarms with sweatshops and peddlers’ carts.”

The Agudas Hamishpocha (a.k.a. the United Families Organization) may have been the only family-based landsmanschaft-type organization in Toronto, and arose from the members’ strong desire to cement their family ties. Like members of a mutual benefit society, they paid dues, socialized at weekly meetings, and received access to free loans and other privileges; many got started in business through such loans. My grandfather, Isaac Naftolin, was the founding president and my grandmother Esther was a founder of the Ladies Auxiliary. In 1938 cousin Nochem Naftolin penned a ten-page essay (in Yiddish, of course) outlining the origins of the group, and laying down the central themes of the family saga in the process.

“We had to uproot our homes (from) our birthplaces in Russia, the land of fury and rage, because back there, every free thought was suppressed, and here, in free America, we found freedom, equality and brotherhood,” he wrote. “We settled in Toronto and each one found an occupation suited to his talent. We worked, we made a living, and we raised children. The children grew up and went through school. They made friends, married and established families of their own, to the point that they dispersed and seldom had the opportunity to see the others. This is how, over the years, we became distant from each other. The older members of the families looked upon this development — how kinfolk were becoming estranged — with disappointment.”

If relatives were proud to celebrate the Agudas Hamishpocha’s 10th anniversary in 1938, the occasion of the 80th anniversary luncheon in August 2008, with about 160 relatives in attendance, was also the source of immense pride. Having the support of such a large family group has been of tremendous benefit in my publishing project. Last April at least 125 people, mostly cousins, attended my book launch, which a relative generously sponsored and which took place in an auditorium offered by the Ontario Jewish Archives. It was a thrill to be confined to a desk, signing newly-purchased copies of my book for more than an hour.

* * *

One Hundred Years in Canada: the Rubinoff-Naftolin Family Tree is 384 pages long and contains more than 600 photos and illustrations and well over 100 elaborate genealogical charts. The process by which it came to be produced may be helpful and instructive to genealogists contemplating a similar project. Through all of my endeavours I was guided by Patricia Law Hatcher’s sensible book Producing a Quality Family History, which includes this useful definition:

A quality family history

- presents quality research — thorough, new, & based on a variety of primary sources;

- is well organized, understandable, and attractively presented;

- uses a recognized genealogical numbering system;

- documents every fact and relationship fully;

- expresses information accurately, indicating the likelihood of conclusions;

- goes beyond records, placing people in context;

- includes illustrations, maps, charts, photos; and

- has a thoughtful and thorough index.

Just as production of a family tree book necessarily entails learning a great deal about a family history, so too — since the project seemed far too complicated and elaborate for me to hand it over to someone else — was it requisite that I master the art of book production and design. I identified three primary components of the project: the narrative, the visual material (photographs, illustrations and maps), and the genealogical charts. All of these elements had to be “married” together in a pleasing format on the page. It was helpful that, as a writer and editor, I had worked occasionally with designers over the years and learned much by osmosis.

Writing the narrative took up much of my spare time for about five years, including at least two weeks around Hanukkah each year. I found it imperative to identify the “Who, When and Why” questions outlined above; to be analytical; to fill in gaps; and to integrate all the tiny threads of my research into a coherent tapestry. A golden rule of building the narrative, I discovered, was to obey “chronology” as much as possible. Putting events into a strict time sequence is an imperative part of understanding and telling history. Each chapter of the manuscript had to be circulated to a team of volunteer proofreaders for comments and corrections.

Photos and illustrations came from diverse sources. Many were supplied by relatives in Toronto; my preference was for old photos showing the pioneering generation of immigrants and their children. Several relatives whose grandparents had stayed in Russia, and who themselves had moved from the Former Soviet Union to Israel and Germany in more recent times, supplied photos from their branches. One new-found relative in Dnieprepetrovsk sent me a copy of a photo-postcard that my grandmother in Toronto had sent to her relatives in Zhlobin in 1911. Interestingly, the Toronto postmark and the Zhlobin postmark both show the same date: the overseas postal voyage must have taken 13 days since the calendars were then 13 days apart.

Many archival documents were reproduced in miniature in the book; their legibility, even at reductions of 50 percent or less, holds up surprisingly well. Explanatory captions should accompany such items to spell out their particular relevance or significance. For example, if a birth document confirms a rare town name as the birthplace, let the reader know, even if it seems obvious to you. Other illustrative material included ads of family-run businesses from old newspapers and city directories: I was thrilled, for example, to include an advertisement of my great-grandfather’s scrap metal business from the 1920 city directory. In the City of Toronto Archives I found a photo of the old train station, circa 1907, where many of the immigrants had arrived; and photos of streets where many had lived in the early years of the last century. Such material from a number of archives was useful in illuminating the family saga in a more general way.

Adobe Photoshop proved an indispensible tool for improving, repairing and cropping photos and graphics. Many an old faded photograph was given new life through computer adjustment of the tonal quality via its “histogram” balance. Basic photo repairs were accomplished through the phenomenal wizardry of Photoshop’s spot healing and repair tools. The program’s artistic filters instantly “feathered” the outlines of some photos for attractive word-wraps, and transformed others into attractive illustrations. Some black-and-white photos were colourized for use on the front cover, which involved a carefully composed montage — again, constructed in Photoshop.

As for genealogical charts, I wanted the book to present a full range sweeping across all five branches of the family tree, yet I was averse to relegating the task to Family Tree Maker, the lowest common denominator of computer software. Unfortunately, Easy Tree, the wonderful program that later metamorphosized into the equally wonderful Sierra Generations, was abandoned by its developers in the 1990s and had not advanced beyond a Windows 98 environment. As I consider its chart-making capabilities greatly superior to those of Family Tree Maker, I have kept a Windows 98 laptop computer in good repair for the express purpose of drawing charts in Sierra Generations-Easy Tree.

The chart-making process proved quite complicated. As a first step, the charts were designed on the Windows 98 laptop, proof-read and corrected, then printed out in the best quality possible. (A compact, non-serif and matchable Ariel typeface was used.) Next, they were scanned at 600 dpi to make them “scalable” and accessible in a Windows XP environment. Each chart was then dropped into the book design software program and tailored in Photoshop to fit its particular space on the page. Charts too big to fit on a single page were brought across the margin to go over a double-page spread. In such cases gaps had to be added at strategic positions in the charts so that nothing would be lost in the “gutter.” All later additions and corrections to the charts was accomplished using Photoshop’s text feature.

Those planning to publish a family history must make several important decisions at the beginning of the process that will greatly affect its outcome. What size book is required? Will there be a budget for colour photographs and glossy paper? In my case, I wanted a large page size, perhaps 10” by 12”, because of the many elaborate charts. However, I was drawn to Lightning Source International, a Tennessee-based publisher with a revolutionary and economical new Print on Demand system that was highly recommended.

LSI’s largest format was essentially an 8-1/2” by 11” page. Could my charts be made to fit comfortably into that format? And would I be happy with a softcover book on photocopy-quality paper, the only available option at that size? LSI offered good photo reproduction at any size, but I knew I’d be getting a “popular” rather than a deluxe edition. The company’s low set-up fee, its ability to print one or 10,000 copies of a title at the same unit price, and its facility to ship books directly from its plant, were factors that helped persuade me to go with LSI. In the end, LSI was definitely the right choice and I was 100 percent pleased with the outcome.

For a design software program, I chose Adobe InDesign, costing about $800. This is a very powerful, very complex program that requires a steep learning curve: I utilized many online tutorials and read the manual repeatedly until I mastered it. For some years I had been gathering various design elements — a scroll, a menorah, a title page box — that for possible use one day. As to design, the page was divided into two columns, allowing for easy legibility despite an 11-point font size, slightly smaller than usual. The Notes section utilized a ragged-right three column format, and was enhanced by many photos and illustrations that did not fit in the main section of the book.

A first-time book designer is confronted by many challenges. To publish a title with LSI, one must be a registered company, so I paid out provincial licensing fees and founded Now & Then Books. An ISBN number was attained from Libraries and Archives Canada (as it is from the Library of Congress in the United States). The title page also required “Cataloguing in Publication” data from Libraries and Archives Canada. A statement of copyright is also a good idea.

Another requisite component, of course, is a Table of Contents; for a more “user-friendly” experience, I also compiled a List of Genealogical Charts, which ran over four pages. The book was divided into five chapters, one on each branch of the family, and a sixth on the Agudas Hamishpocha. There was also an introduction and sections for appendices, notes and a series of indices. It is often said that a genealogical book is no better or no worse than its index. Without the facility to look up a particular person or family name in an index, a genealogical book is of limited use to many researchers.

If, as a publisher, you are mistaken if you suppose that your work is done once your book is published. Promotion is required to get your baby out into the world. You may wish to build a web site (mine is at http://rubnaft.com), send out an e-mail announcement, ask your local Jewish book store to put a few copies on display. With a bit of luck, you may be running back and forth to the post office for weeks. ♦

PHOTOS

(Top) POSTCARD OF ZHLOBIN, BELARUS, CA 1900 — This postcard from a cousin carried a message on the back pointing out the location of the family’s blacksmith shop as well as a theatre along the town’s Market Street. Zhlobin was one of about a dozen villages, including Rechitsa and Streshin, where family members lived before leaving for Canada a century ago.

(Middle) BOOK COVER — Three primary elements — textual narrative, more than 600 photographs, and more than 100 genealogical charts — were combined in his family history book, writes Bill Gladstone of his 384-page book, One Hundred Years in Canada: the Rubinoff-Naftolin Family Tree, published in 2008.

(Lower) AGUDAS HAMISHPOCHA 1938 — Executive members of the author’s Toronto-based family society, the Agudas Hamishpocha, posed for a 10th anniversary photograph in 1938. His grandparents, Isaac and Esther Naftolin, are in the second row, second and third from left. The Society still meets for breakfasts six times a year.