From Canadian Jewish News, July 2017

Simcha Simchovitch, a Polish-born Holocaust survivor and prominent poet and writer in both Yiddish and English, died in Toronto on July 12, 2017 at the age of 97.

The winner of various literary prizes including several Canadian Jewish Book Awards and two I.J. Segal awards for Yiddish Literature, Simchovitch was one of Canada’s senior Yiddish writers; yet he proved equally adept in both English and Hebrew. His only novel, Stepchild On The Vistula (Shtifkind Bay Der Vaysl), was autobiographical although told in the third-person narrative voice of a fictional character.

Simchovitch originally wrote it in Yiddish and later translated it into English; it was translated in Polish about ten years ago and published with a laudatory introduction by Elie Wiesel. Soon afterwards, the Polish Government invited the author back to his hometown of Otwock for a public ceremony honouring him and the book. “He was guest speaker — it was a beautiful event,” said his daughter, Itta Mandarano. “It was his only time back to Poland since the war.”

Born in 1921, Simchovitch grew up in Otwock and left his parents’ home as German planes threatened death and ruin. The Nazis murdered most of the town’s Jews in 1942: Simchovitch professed a sacred duty to bear witness and to remember. “My main goal in writing is to commemorate my parents who were killed in the Shoah — my little brother, my three sisters, my friends in the youth organization,” he told The CJN before his 85th birthday. “I’m glad I was able to write about them in poetry, to immortalize them.”

He also made it his mission to write about the vibrant Jewish life that existed in Poland in the interwar years (1918 to 1939), a period whose culture and history he felt had been overlooked. Shtetl literature by the likes of Sholem Aleichem and other writers elegantly captures an early time, but far fewer words have been written about Polish-Jewish life in the 20th century, he asserted.

“There were three and a half million Jews in Poland then. There was an intensive Jewish life, religious and secular. There were youth organizations, political organizations, sports clubs — there was so much. All of this dispersed, all of this was wiped out, and there was no time for the writers of the new generation to appear and to tell their stories. So this I felt was my main task: to re-create this life.”

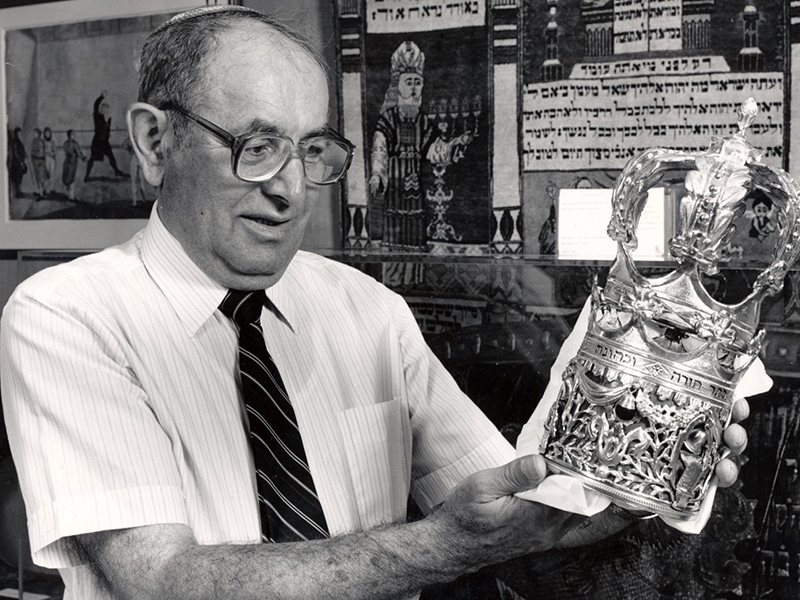

Having escaped the war in Siberia, Simchovitch returned briefly to Poland after the war and saw firsthand the cruel devastation of his beloved hometown. He wrote his first poem in 1946 and his first collection, Thus A Youth Perished, appeared in 1950, after he and his wife had landed in Montreal. He worked in a leather factory for two years, took some courses at the Montreal Jewish Teachers Seminary, and taught cheder in Ottawa for six years. In the mid-sixties he and his family moved to Toronto, where he was principal of the Borochov Centre, then curator of the Judaica Museum of Beth Tzedec Congregation.

At the culmination of his studies, for which he earned a masters in Hebrew literature from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, he wrote a Hebrew thesis on the 18th-century Jewish philosopher Solomon Maimon; it appeared in 1972. Stepchild on the Vistula was his only other book-length work.

“This I wrote in one summer, in about ten weeks in Ottawa during a summer vacation. I went every day to the school and the school was closed, and I wrote every day. It [a draft manuscript] had been lying around for many years because I was studying. After my studies I dug it out and edited it,” he told The CJN in an interview about ten years ago.

In fact, Stepchild On The Vistula was based on a much earlier work that was apparently lost. In the late ‘30s, Simchovitch responded to a campaign from the YIVO Institute, seeking autobiographical essays from young people. “I wrote down my story and sent it to them, then war broke out. Afterwards I tried to trace it at YIVO in New York. They have a list of submissions: my name is there but my original is missing.”

Simchovitch continued to publish new works even in his eighties. A book of poetry, Sorrow and Consolation, appeared in 1989 and three more books of Yiddish poetry followed in the ’90s, as well as several collections and a collection of essays. As well, singer Lenka Lichtenberg has put some of his poetry to music.

In 2001 Simchovitch published a collection of Yiddish songs by Mordechai Gebirtig that he had translated into English. A reviewer in The CJN said that reading Gebirtig’s poems as translated by Simchovitch was “like peering through a window of a time capsule into the world of European Jewry that Hitler destroyed.” He also translated and edited A Woman of Valour: Memoirs of Gitl Hopfeld, a memoir by his aunt about how she and her two children survived the Holocaust.

Stephen Creed, a longtime friend who first encountered Simchovitch at Beth Tzedec, took him to various lectures and cultural events, some of which Simchovitch would cover journalistically for the New York-based Yiddish Forward. “Once I took him to the Inn on the Park to a ceremony where he was being honoured and an endowment fund was being named after him,” Creed said. “I got involved with him because I could see he was a great person. He represented our people during the history of the 20th century, from pre-Holocaust to post-Holocaust — he was a sort of bridge.” ♦