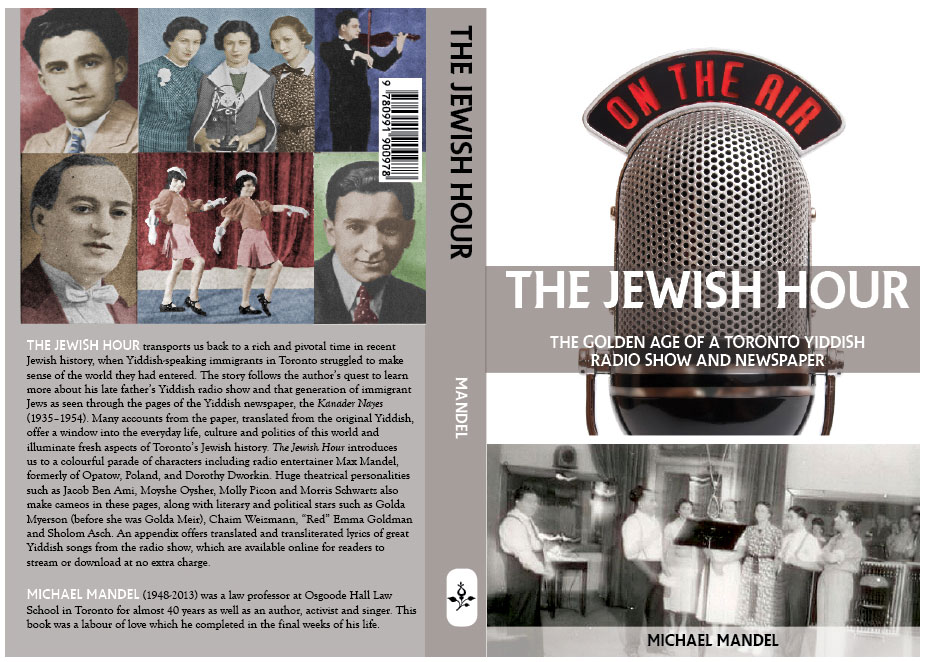

Dorothy Goldstick (later Dworkin) donned the modest white cap of a maternity nurse in 1909, but her accomplishments ranged into charitable work and philanthropy, business, newspaper publishing, and institution building on a scale that benefitted the entire city of Toronto.

Dorothy Goldstick (later Dworkin) donned the modest white cap of a maternity nurse in 1909, but her accomplishments ranged into charitable work and philanthropy, business, newspaper publishing, and institution building on a scale that benefitted the entire city of Toronto.

A driving force behind the establishment of Toronto’s world-famous Mount Sinai Hospital, Dworkin (1889-1976) was designated a Person of National Historic Importance by the Canadian government several years back — a designation, former Environment Minister Jim Prentice said, that “will help to ensure that her important contributions to Canada’s rich cultural heritage are appreciated and remembered by future generations.”

Dworkin took her first ride in an automobile while going to a delivery with Dr. Samuel Lavine, Toronto’s first Jewish doctor, who cranked the motor frantically to get it started. “I told Dr. Lavine how thrilled I was to drive in a car, but he suggested that I should not count my chickens before they hatched,” Dworkin later recalled. “One never knew whether the car would keep going or for how long.”

Many Jewish immigrants, Dworkin found, were terrified of hospitals, regarding them as a temporary stop before the cemetery. She finally persuaded one poor woman, who was in prolonged labour for two days, that a hospital would be better place for her than her tiny impoverished home. “The ambulance arrived, the patient was on the stretcher — but at the last minute, she panicked. Her baby came quickly after that. . . . a healthy, normal child.”

About 1909, Dworkin took a lead role in opening a Jewish medical dispensary on Elizabeth near Agnes (Dundas) in the old Ward neighbourhood that was thronging with recently-arrived Jewish families. The dispensary proved popular because the staff spoke Yiddish and visits cost only 50 cents instead of the $1 charged at other facilities. Drugs were supplied by the Hashmall pharmacy.

She left the dispensary in 1911 when she married Henry (Harry) Dworkin, but the impetus for a Jewish hospital, where elderly patients might receive kosher meals and be understood in Yiddish, remained strong. After a decade of fund-raising and planning, Dworkin — in league with the Ezras Noshem women’s charity and a group of Jewish doctors eager for a place where they might be allowed to practice — opened the Toronto Jewish Maternity and Convalescent Hospital at 100 Yorkville Street.

She left the dispensary in 1911 when she married Henry (Harry) Dworkin, but the impetus for a Jewish hospital, where elderly patients might receive kosher meals and be understood in Yiddish, remained strong. After a decade of fund-raising and planning, Dworkin — in league with the Ezras Noshem women’s charity and a group of Jewish doctors eager for a place where they might be allowed to practice — opened the Toronto Jewish Maternity and Convalescent Hospital at 100 Yorkville Street.

Ezras Noshem had raised $12,000 — “most of it in nickels and dimes,” according to historian Lesley Marrus Barsky — for the down-payment on the $35,000 building, an aging structure that had already served as a private hospital for decades. The original 20-bed facility, which became the first Mount Sinai, is no longer standing; the hospital façade that is visible on Yorkville today was the result of a 1935 expansion. Dworkin was again on hand when the new and much-expanded Mount Sinai opened on University Avenue in 1953.

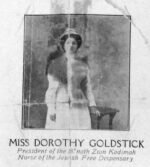

Dworkin funeral 1928

Tragically, Dworkin became a widow in 1928 when Henry Dworkin was killed by an automobile at Queen and John streets; a businessman and founder of the Labour Lyceum and a friend to countless immigrants whom he and Dorothy helped, Henry’s reputation was such that his funeral cortege drew an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 spectators.

Dworkin took over her late husband’s philanthropic and business affairs, which included a travel and steamship agency, bank and tobacco shop, of which a profitable sideline was importing and selling daily Yiddish newspapers at street kiosks around the city. In 1935 Dworkin began publishing a small Yiddish newspaper, the Keneder Nayes (“The Canadian News”) which was distributed as a free insert in the Yiddish papers that arrived each morning from New York.

Thus, Dworkin maintained a significant influence over the Yiddish-speaking community of Toronto at least until 1954, when the paper folded. This important but little-known aspect of her career is spotlighted for the first time in the recent book, The Jewish Hour: The Golden Age of a Toronto Yiddish Radio Show and Newspaper, by Michael Mandel (Now and Then Books).

“The story of Dorothy Dworkin,” said federal minister Jason Kenney at the ceremony honouring Dworkin as a Person of National Historic Importance, “is a fine example of how immigrants influenced the history of Canada and helped make it the rich and diverse country it is today.” ♦