◊ From the Canadian Jewish News, March 2020

◊ From the Canadian Jewish News, March 2020

As Jews throughout history have been all too aware, tragedy, whether large or small, is never all that distant from the everyday realm of human affairs.

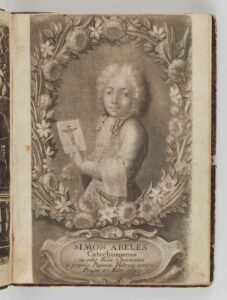

This sad chain of events took place in Prague in 1693 and 1694. The central figure was a twelve-year-old boy named Simon Abeles who came from a well-known Jewish family. He was the grandson of Moses ben David Bunzel Abeles, the “primátor” or mayor of the Jewish community of Prague.

This sad chain of events took place in Prague in 1693 and 1694. The central figure was a twelve-year-old boy named Simon Abeles who came from a well-known Jewish family. He was the grandson of Moses ben David Bunzel Abeles, the “primátor” or mayor of the Jewish community of Prague.

Simon was unhappy at home and had bitter disagreements with his father, a merchant named Lazar Abeles. At the time a local Jesuit order, St. Clement’s, was conducting an aggressive missionary campaign, intended to attract and convert Jewish adolescents and youth to Christianity. Simon ran away and found shelter among the Jesuits, who began to instruct him in the basics of the Christian faith.

In this religious tug-of-war over souls, it mattered little that the boy was hardly of an age to give his informed consent; parental consent wasn’t even a factor. The twelve-year-old allegedly consented to be baptized and was “secretly preparing for the sacrament at the Jesuit College in the Old Town of Prague.”

Even after his father found him and brought him back home, Simon continued his rebellion. Push led to shove until matters took a tragic turn. What actually happened remains unverified but, according to at least one source, the father and a cousin, Löbl Kurzhandl, “gave the boy such a severe beating that he fell and broke his neck.”

Rather than face up to what they had done, the two hurriedly buried the boy and afterwards claimed he had died of natural causes. But as Shakespeare wrote in The Merchant of Venice, “Murder cannot be hid long . . . [and] in the end truth will out.” For manslaughter, it is much the same.

Or was it something else? Perhaps the father was framed through a series of cunning official lies. We’ll never know the truth.

In any event, a “denunciation” from an unknown party brought the affair to the attention of the authorities, and the body was exhumed for a basic post-mortem examination. Evidence of what we might now call “foul play” was found, and those same “authorities” (for there were no police in those days) detained the father, his third wife, and their cook.

In any event, a “denunciation” from an unknown party brought the affair to the attention of the authorities, and the body was exhumed for a basic post-mortem examination. Evidence of what we might now call “foul play” was found, and those same “authorities” (for there were no police in those days) detained the father, his third wife, and their cook.

The father, his soul tortured and now fearful of being bodily tortured, hung himself in prison with his phylacteries. Then the authorities arrested the cousin, Kurtzhandel, who would stand trial on charges of murder and “in odium fidei,” contempt for the Christian faith. Meanwhile, the boy was received as a glorious martyr by the Church and buried in a public ceremony in the Tyn Church of Prague.

Upon his conviction, Kurtzhandel was sentenced to be “broken on a wheel,” an extremely cruel method of execution that involved the crushing of bones. But the Bohemian appellate court reduced his punishment to beheading after he confessed to the accidental killing and consented to be baptized.

Seeking to beatify Simon, the Jesuits published a hagiographic narrative of how he suffered and died for his faith and the sensational trial that followed. In the 1960s the Jewish Museum of Prague acquired a copy of this very rare book after it surfaced in a second-hand bookshop.

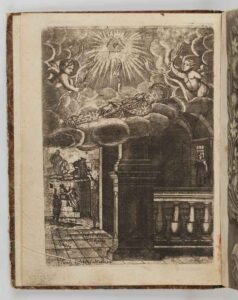

Not surprisingly, the book provides a Christianized and highly biased version of events, replete with miracles, improvised facts, and much antagonism towards the Jews. It also contains several illustrations of the poor martyr, including one where he is being greeted reverentially by angels in the clouds as he ascends to heaven.

At least one popular song made the rounds, extolling Simon’s pure faith and lamenting his tragic end, “killed by his father in a moment wild,” and instilling the “grief of the vast multitude.” According to a historical Chronicle of Bohemia from 1854, poor Simon “was buried with great pomp as a martyr, in a glass coffin, on the right side of the altar in the Týn Minster in Prague.”

Just another footnote of history as the wheel of human fortunes continues its relentless spin. ♦