Becoming Hapsburg: The Jews of Austrian Bukovina, 1774-1918, by David Rechter. Hardcover, 214 pages. Published by The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. Portland, Oregon, 2013. www.littman.co.uk

Author David Rechter, a research fellow in Modern Jewish History at Oxford, has made a full-length and comprehensively researched study of the Jews of Austrian Bukovina, beginning with the Austrian occupation of 1774, to the First World War, when Bukovina dissolved as a politico-geographic entity.

Author David Rechter, a research fellow in Modern Jewish History at Oxford, has made a full-length and comprehensively researched study of the Jews of Austrian Bukovina, beginning with the Austrian occupation of 1774, to the First World War, when Bukovina dissolved as a politico-geographic entity.

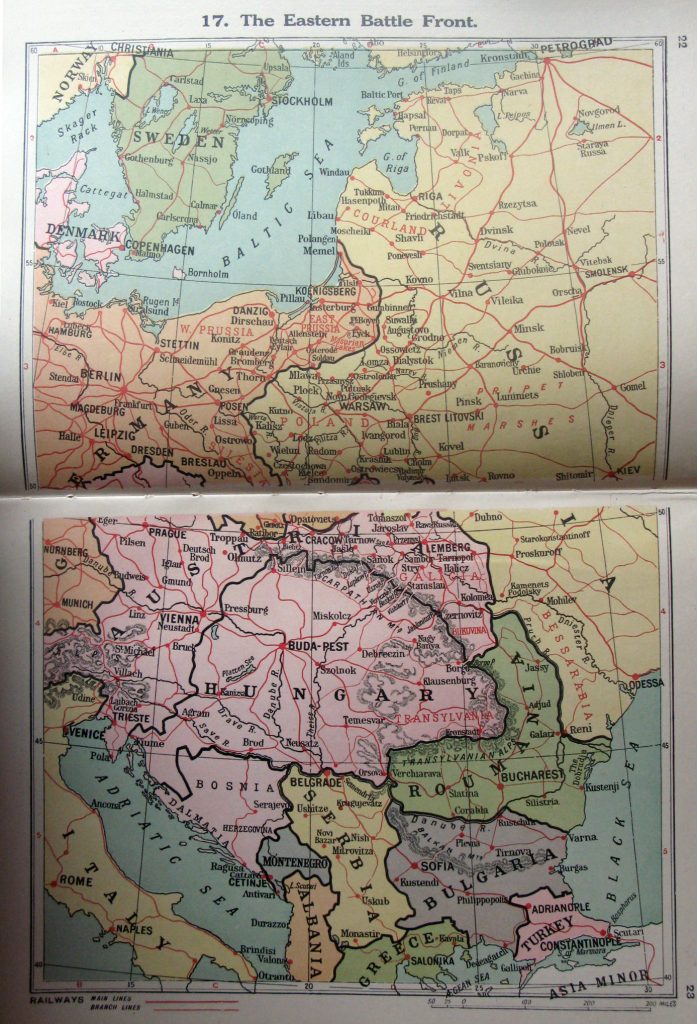

Bukovina (the name comes from the Ukrainian and Slavic words for beech trees) was part of Moldova and then the Ottoman Empire before the Austrians annexed it, ostensibly to enable better transportation between Galicia and Transylvania.

A landlocked territory on the central-eastern slopes of the Carpathian mountains and adjoining plains, Bukovina was surrounded by Galicia, Bessarabia and Romania.

Today its northern half belongs to Ukraine, its southern half to Romania. Its largest city, Czernowitz, is in Ukraine and smaller centres such as Radautz and Suceava in Romania.

Rechter writes that Bukovina was considered “a Jewish El Dorado” for a time before the dissolution of the Empire because it had the highest proportion of Jews in its population of any Austrian crownland (more than 100,000, representing about 13 per cent of the population just prior to WWI). The Jews were one of five national or ethnic groups that maintained a “sometimes uneasy equilibrium” in Bukovina, Rechter asserts, “with none able realistically to claim political or cultural dominance in the manner that the Poles achieved in Galicia.”

Czernowitz was the fourth largest Jewish city in Austria, after Vienna, Lemberg (Lviv) and Krakow, yet it had a higher proportion of Jews in its population than any of the larger Austrian cities: its 30,000 Jews constituted about a third of its residents and were disproportionately prominent in commerce, the professions, the arts and politics.

Bukovina was perhaps the best example of the view of the Habsburg state as a benevolent protector of the Jews from the worst excesses of antisemitism and belligerent nationalism that arose in diverse quarters of the Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century.

But that was certainly not the case in the period of the Josephinian Enlightenment (1780s) to emancipation in 1867, when Bukovinian Jews were repeatedly compelled to withdraw from various professions; indeed, thousands were expelled from the region altogether.

When the Austrians first arrived, Czernowitz was a muddy village of several hundred mostly wooden structures and a population well under 2,000; Suczawa was no bigger. They regarded the few thousand scattered Jews in Bukovina as “pariahs,” Rechter notes, “part of a barbaric landscape inhabited by exotic and uncivilized peoples.” The climate of tolerance, even the reforms of 1848, were slow to reach the backwater of Bukovina; the Jews suffered but seemed to flourish nonetheless. Despite the harsh restrictions and animosities, the Jewish population rebounded and grew faster than in any other Austrian territory.

With his well-read historian’s eye, Rechter paints a detailed portrait of life in centuries past. He writes that Bukovinian Jews, along with others, “exported, for example, wool to Hungary, Poland, and the German lands, honey, wax and butter to Istanbul, cattle to Transylvania and Galicia, raw hide to Hungary, sheep and goats to the Levant, and horses to Poland, while importing leather and fur from Russia, iron from Turkey, glass from Poland and Ukraine, cooking salt from Galicia, wine from the Romanian territories, and all manner of manufactured and luxury goods from Istanbul, Venice, and the fairs in Frankfurt, Leipzig, and Breslau.”

By the 1880s the Jews of Bukovina were quite different than their counterparts in Galicia because they thrived in a society “with its own particular Habsburg construction: a Polish-Galician foundation with an Austrian-German superstructure,” as opposed to Galicia, where the Poles held sway.

But the “Jewish Eldorado,” if it ever truly existed, could not last. Although it has been overshadowed by the Holocaust, the 1914-18 war brought immense destruction and suffering to millions of Eastern Europe Jews, Rechter notes, and brought Bukovina crashing to its end.

“Neither Habsburg Bukovina nor the Jewish society that had developed there over the course of 140 years of Austrian rule survived the war,” he writes. “The Russian invasion of the province in September 1914 signalled the beginning of the end; almost at a stroke, the fabric of Jewish society began to unravel as its leaders were scattered, its institutions ceased to function, and its cities, towns and communities were decimated.”

This finely-wrought historical study takes into account the various factions of Jews in Eastern Europe at the time, from Frankists to Hasids to those reformed by the Enlightenment; and familiarizes the reader with a diverse array of political and cultural leaders of the day. The extensive bibliography lists hundreds of books and other sources. The book includes two useful sketchmaps, one showing the main towns and cities of Bukovina, the other showing its location in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire of 1910.

From Avotaynu, 2014