From Avotaynu, 2020

Book Review: A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Italy, France and “Portuguese” Communities, by Alexander Beider.

Like a Napoleon of names, Alexander Beider has been sweeping methodically across the Jewish diaspora seeking to apply a rigid scientific methodology to the naturally-occurring phenomenon of Jewish surnames.

Like a Napoleon of names, Alexander Beider has been sweeping methodically across the Jewish diaspora seeking to apply a rigid scientific methodology to the naturally-occurring phenomenon of Jewish surnames.

Beider has devoted more than three decades to their study, compiling a library shelf of impressive tomes including A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Kingdom of Poland, A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire, and similar volumes for Prague and Galicia. Among his other significant works, he has also produced massive studies on Jewish Ashkenazic names as well as the Origins of Yiddish Dialects, the latter of which was published by the Oxford University Press. (Most of the others were published by Avotaynu.)

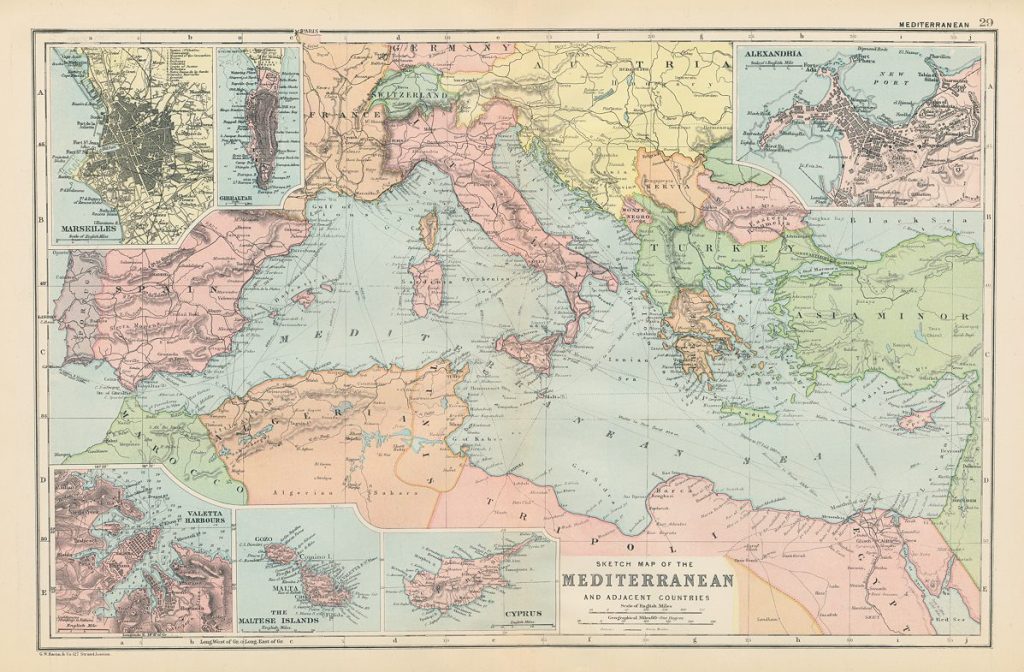

In recent years Beider has turned his attention to Sephardic and other lesser-known Ashkenazic communities from the overlooked to the exotic. His Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Maghreb, Gibraltar and Malta appeared three years ago. Now the trend continues with the present work, A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Italy, France and “Portuguese” Communities (wherever they happen to be).

As mentioned in a subtitle, the dictionary includes surnames “from continental Italy, non-Ashkenazic communities in France, and Sephardic communities in Western Europe (after the 1490s) and the Americas.” The surnames come from many places, including Rome, Ancona, Florence, Siena, Pisa, Livorno, Bologna, Ferrara, Mantua, Cremona, Milan, Venice, Verona, Padova, Genoa, Turin, Nice, Avignon, Marseille, Narbonne, Bordeaux, Bayonne, Amsterdam, London, Hamburg, Curacao, Jamaica and Barbados.

Standard in most of Beider’s works is a long erudite examination of the surnames under study. In the present work, as usual, this section requires very careful and concentrated reading. I first began the task while under self-isolation due to the coronavirus, and I admit I could not muster the sustained concentration level necessary to navigate all the way through this dense woods. But many of the trees that I glimpsed in passing seemed magnificent.

Of the book’s 872 pages, the beginning section is some 236 pages long, including 20 pages of bibliography. As usual with Beider, it provides a comprehensive survey of all previous scholarship on the subject. Dozens of etymological questions are posed and many are resolved. Beider puts under his magnifying glass such diverse topics and minutiae as using “Portuguese”-derived surnames as a tool for analyzing their history, Jews in the Papal States, the Crypto-Jews of Nantes and Rouen, and the question of whether the New Christians of France merged with the French Catholics. Standing on their own, some of these topics could theoretically be expanded into treatises or even books.

Chronological reading of this book is not essential and readers should feel free to dip into it as they wish: this is a reference work, not a novel. However, the part on How to Use This Dictionary should not be skipped for it provides the key to understanding how the surname entries are organized. For each surname, the dictionary provides dated references of where and when the name was first used, its categorization by group, and its likely etymology.

For example, the entry for the surname Efrati indicates that its first documented occurrence was in Rome in 1571, and it also appeared in Livorno in 1658 and Amsterdam in 1787. The dictionary further classifies it as part of the Old Iberian and/or Italian surname groups, then offers two etymologies, including a derivation as a patronymic or nickname-based name referring to “one from the tribe of Ephraim” as cited in 1 Samuel 1:1.

Unlike many of his previous Dictionaries, Beider has not done an inductive survey of original archival documents and other material to collect these surnames; rather he has pored over virtually all extant scholarly sources and other secondary material: hence the huge bibliography. Because it traces the significant usage of each morphological unit chronologically through history (usually from 1492 onward), it bears more than passing resemblance to the original Oxford English Dictionary. And like the OED, it is a masterful achievement of compilation.

Many of the surnames covered in the book seem exotic and fascinating, as do the categories. The names Avila and Azubel are categorized as Old Iberian/Portuguese; the surnames Avigdor and Cremieu as Southern France; the surnames Jerusalem, Montefiore, Naftalin and Sabatini as Italian. (My mother was a Naftolin from Belarus, but that’s a different etymology.) Arpa, a name used in Mantua as early as 1557, is an occupational surname for one who plays the harp. (Could it be related to the surname Arfa, found in Poland?) The Italianate name Balestra is also occupational, referring intriguingly to a crossbow.

Portuguese-derived names comprise one of the larger groups; they are found from Cremona to the Caribbean, a result of the Spanish Expulsion in 1492. Portuguese-derived names include Barzilai, Belisario, Belmonte, Espinosa, Flamengo, Gideon, Granada, Jesurun, Mendes, Mendoza, Mercado, Nunes, Pereira, Pisarro and Velasco.

Beider also found a surprising multitude of Ashkenazic names in these territories, evidently a result of cross-migration. Examples include Arnstein, Aschenazi, Auerbach, Austerlitz, Bachrach, Baumgartner, Grunhut, Luzatto, Oberdorfer, Oppenheim, Popper, Rappaport, Tedesco, and Treves.

The popular surname Rappaport has an interesting history. Occurring in the Venice area in 1520, Padova in 1540 and Mantua in 1544, it sprung up as a combination of Rapp and Porto; Rapp being a migrated surname and Porto pointing to one of a series of towns in northern Italy whose names start with Porto.

And the surname Treves, dating from Provence circa 1343, was thought to be originally German, but became associated with the Provence region where the great Talmudist Rashi lived. (Probably for lack of space, Beider does not mention that one of its derivatives was Dreyfuss, a name made familiar through the notorious Dreyfuss affair of the late 19th century.)

The surnames collectively convey a rich sense of history, rooted in the deep past. Those classified as belonging to more than one group include Baruch, Belisario, Benveniste, Caro, Castro, Cohen, Elmaleh, Hakim, Halfon, Pisa, Raphael, Sacerdote and Toledano.

Beider has admirably compressed a great deal of information into a small space, but there are some instances where one wishes he might have taken the discussion a little farther. For example, he parses Halfon into three distinct etymologies, including an occupational name referring to a money-changer from the original Hebrew. While he suggests Halford as a common Christian variant, he does not reference the common Jewish name Helfand, which he has elsewhere linked to the Yiddish word for elephant and the medieval ivory trade.

Dr. Beider has rightfully made a name for himself as the world’s foremost expert on Jewish surnames, and this new dictionary rates as a milestone achievement on its own, even without taking the rest of his incredible opus into account. ♦