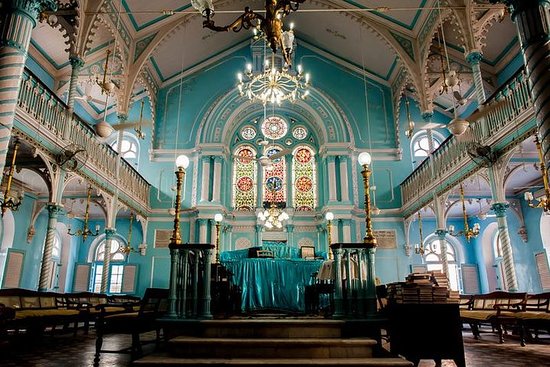

The recently restored Blue Synagogue

Book Review: Bombay: Exploring the Jewish Heritage, by Dr. Shaul Sapir. Large format, hardcover, 290 pages; full-colour interior, lavishly illustrated with large four-panel foldout map. $50. Published by Bene Israel Heritage Museum and Genealogical Research Centre, India, 2013.

There are four distinct historic Jewish communities in India — the Cochin or Malabar Jews, the Bene-Israel Jews, the Bene-Menashe Jews of northeast India, and the Baghdadi Jews, author Shaul Sapir explains at the start of this magnificently presented coffee-table book.

While the first-mentioned communities arrived in antiquity, the Baghdadis were the most recent arrivals. Descended from Jews born in Iraq and other Muslim countries (Afghanistan, Iran, Yemen, Syria), they began arriving in India about 1730, clustering in and around the cities of Bombay (Mumbai) and Calcutta (Kolkata). While many escaped persecution in their former homelands — a familiar story — many were also attracted by the enormous mercantile opportunities that these flourishing cities offered under British rule.

India’s Baghdadi Jews supposedly comprised only about ten per cent of the country’s Jews, and the Baghdadis in Bombay were historically only two per cent of the total. Sapir devoted nine years to researching this particular group which had a disproportionately huge and beneficial influence upon the city. He interviewed hundreds of community members (present and past) and dug up every bibliographic reference he could.

India’s Baghdadi Jews supposedly comprised only about ten per cent of the country’s Jews, and the Baghdadis in Bombay were historically only two per cent of the total. Sapir devoted nine years to researching this particular group which had a disproportionately huge and beneficial influence upon the city. He interviewed hundreds of community members (present and past) and dug up every bibliographic reference he could.

The Baghdadi Jews of Bombay succeeded as traders and bankers, profiting by their advantageous situation between East and West. The towering figure of David Sassoon (1792-1864), whose family dynasty was referred to as “the Rothschilds of the East,” plays a leading role in this history. A wealthy Jewish merchant, Sassoon fled from Baghdad in 1832 and established the house of David Sassoon & Co., gaining enormous success and wealth through the opium trade and building a trading operation that extended to China, Japan, Africa and Eastern Europe. It was also said of him that, like the Rothschilds, the main cause of his success was “the use he made of his sons.” His chosen city, beneficiary of the various hospitals and other philanthropic institutions that he funded, erected a statue in his memory.

The book features sections on the historical background, the synagogues, educational institutions, hospitals, Jewish-run banks, industry, office buildings and residences of note, youth movements and clubs, and other sites, monuments and landmarks. There are coloured photographs on practically every page and plenty of detailed maps.

In terms of population, Bombay’s Jewish community reached its peak about 1947, just as both India and the State of Israel were about to declare their independence. The community was then about 30,000-strong but afterwards dwindled precipitously. Sapir asserts there are only several dozen Baghdadi Jews left in Bombay today but Wikipedia puts the figure at about 4,000; in either case, there is no denying the community is but a shadow of its former self.

In terms of population, Bombay’s Jewish community reached its peak about 1947, just as both India and the State of Israel were about to declare their independence. The community was then about 30,000-strong but afterwards dwindled precipitously. Sapir asserts there are only several dozen Baghdadi Jews left in Bombay today but Wikipedia puts the figure at about 4,000; in either case, there is no denying the community is but a shadow of its former self.

Sapir was born in Bombay to a locally-born mother and a father born in Rangoon, Burma: one can imagine that growing up Jewish in such a place, with such an ancestry, must have been a rather exotic experience. He left while still a child and returned decades later to revisit all the sites of his middle-class childhood in the city sections of Deolali and Byculla, enthralled by all he saw.

The author’s expansive descriptions may be too much for readers unfamiliar with the city, and Sapir freely recommends that such readers skip the text and flip through the pages “just for the pleasure of seeing photographs of the citizens, viceroys, governors, princes, architects, engineers, builders and philanthropists of Bombay,” as well as, of course, the many architectural treasures they erected.

Anyone planning a trip to Bombay, or who knows and loves the city well, will find fascination on every page. The 30 pages of footnotes at the back should provide a great many leads for researchers wishing more information. The author, no stranger to the academic method, has been a teacher of historical geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem since 1975. ♦