From Inside Toronto (2017)

My niece Katie gave birth to her first child recently (a boy) and she suddenly realized how little she knew about her ancestors, especially on her father’s side.

Since I’m the family genealogist and a professional one to boot, I gladly volunteered to research her antecedants. Little did I realize that the tree would become so fascinating, how quickly its leafy boughs would fill with so many amazing characters and stories, reaching back so many centuries to medieval times.

Ever since Confederation, most of Katie’s forebears lived in the Sault, Nipissing and other areas of Ontario; some also spilled into Michigan. Before then, however, her roots also variously run through Quebec, United States, England, Ireland and France.

During the War of 1812, some of her ancestors lived in towns on Lake Erie that endured British shelling and were forced to run for the hills. Some resided in Salem, Massachusetts during the witch trials, and in Quebec almost from the days of Champlain. Katie’s seventh great-grandfather, Charles Vezina (1685-1775), was a Quebec woodcarver whose sculpted crucifixes earned him an entry in the Canadian Dictionary of Biography.

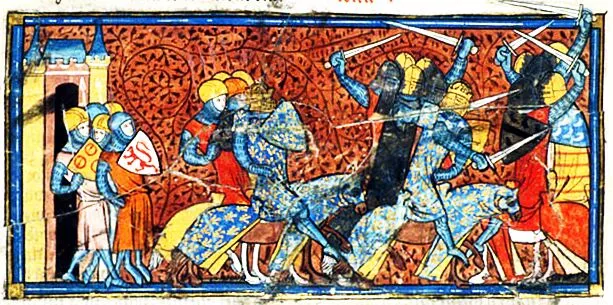

Back in England, some ancestors lived along the fabled Cornish coast, famous for its pirates, while others were in Glastonbury, the town associated with King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. Some were MPs in the early English Parliament while others were barons, lords and ladies. Sir John Oldcastle, an 18th-great-uncle, was a friend of Henry V. Convicted of heresy, he escaped the Tower of London but was recaptured and executed. Ultimately he formed the basis for William Shakespeare’s character John Falstaff.

Richard Oldcastle’s wife, Alice Pembridge (1327-1395), has a pedigree of great antiquity. Her tree includes figures like Ralph De Pembrugge (born 1230), Petronilla Scudamore (1134), Alured De Merleberge (1030) and Rolf Wy Flandrensis (1024), Katie’s earliest-known forefather. This lineage goes back so far in English history that one may reasonably conjecture that earlier generations were Normans or Vikings.

Richard Oldcastle’s wife, Alice Pembridge (1327-1395), has a pedigree of great antiquity. Her tree includes figures like Ralph De Pembrugge (born 1230), Petronilla Scudamore (1134), Alured De Merleberge (1030) and Rolf Wy Flandrensis (1024), Katie’s earliest-known forefather. This lineage goes back so far in English history that one may reasonably conjecture that earlier generations were Normans or Vikings.

It’s thrilling when a research trail leads back far enough to connect to a well-established line, and you can suddenly jump back many generations and add many new ancestors and relatives all at once.

But here’s a conundrum. With every generation back, the number of ancestors supposedly doubles. Katie’s tree goes back an incredible 36 generations, suggesting more than 68 million ancestors. But of course that’s impossible: one must adjust the formula to account for the great many cousin marriages that occur over the centuries. ♦