Etan Diamond, an American academic, has written a full-length study of the Orthodox Jewish community of Toronto and its pioneering movement northward from the inner city into the suburbs in the postwar era.

Etan Diamond, an American academic, has written a full-length study of the Orthodox Jewish community of Toronto and its pioneering movement northward from the inner city into the suburbs in the postwar era.

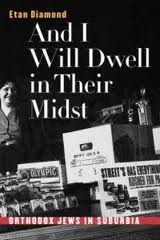

Published recently by the University of North Carolina Press, Diamond’s And I Will Dwell in Their Midst: Orthodox Jews in Suburbia devotes some 200 pages to tracing the development of the significantly-Jewish Bathurst Street corridor, focusing on synagogues, schools, kosher supermarkets, bakeries, restaurants, gift shops and other Jewish establishments. Collectively, such places have stamped a Jewish character onto north Bathurst Street, creating what Diamond calls a “sacred space” that helps to enhance the Orthodox community’s cohesiveness and sense of identity.

A senior research associate at the Polis Center at Indiana University-Purdue University in Indianapolis, Diamond lived in Toronto for three years in the mid-1990s while researching the book as part of his doctoral thesis; his wife and her family are native Torontonians. Upon attaining his degree, he spent another four years expanding his study and preparing it for publication.

“Toronto is very representative of the story I was trying to tell in regard to the geographic migration of the Jews, their progression from urban downtown spaces into suburbia,” Diamond said while signing books recently at the Negev Importing Co., on north Bathurst Street.

According to Diamond,the Jewish movement northward into new subdivisions during the period of great suburban expansion amounted to a sort of quantum leap of faith. At first glance, the vast commercial expanses and overarching consumerist ethic of suburbia seem entirely at odds with the spiritual values of Judaism, he said.

“It had always been assumed that Jews were somehow urban people. They had always been associated with urban spaces. Now they were saying, ‘We’re going to move to the suburbs and have our big houses and lawns, but we’ll all live near each other and still keep kosher and maintain our Judaism ….

“One of the big surprises of my research was the extent to which there was an awareness, particularly in the Canadian Jewish News in the 1960s when it all started, that the movement up Bathurst Street was something historic and important.”

Much of the author’s research was conducted at the Ontario Jewish Archives, examining synagogue records and reading back issues of the Canadian Jewish News and the Jewish Standard. He also consulted property records and interviewed more than a dozen Torontonians.

Several of his subjects described the experience of moving, four or five decades ago, into newly-built houses on streets in the wilds of North York, adjacent to farms and accessible only by unimproved roads. Others recalled the early days of synagogues such as Shaarei Shomayim, whose congregants, seeing the writing on the wall, transplanted themselves northward and broke ground on the present Glencairn Avenue building in 1964.

Still others recalled erecting new synagogues in stages, starting with the social hall, and adding the religious sanctuary as funds became available. That model of pioneering has been refined and accelerated to the point where, in the 1990s, developer Joseph Tanenbaum could build a neighbourhood in Thornhill and erect the mammoth Beit Avrahum Yoseph of Thornhill synagogue practically in a single swipe.

Diamond documents the Jewish community’s unusual “hyper-linear” evolution along Bathurst Street, and concludes that other areas of settlement, such as on north Bayview Avenue, never reached the same level of concentration.

“Everybody knows Bathurst Street. You just have to say the word and everyone understands it. All of Jewish life happens in and around Bathurst Street: it’s the icon of Toronto Jewry. If you meet someone in Israel and you tell them you’re from Toronto, they’ll say, ‘Oh, Bathurst Street.’“

Several maps, tables and historic photographs add to the book’s interest. A sketch map chronologically outlines seven stages of the Jewish community’s development: Kensington Market (1900 to 1960), Forest Hill (1930 to 1950), Lawrence Manor and Clanton Park (1950s), Bathurst Manor (1960s), Bathurst Village (1960s to 1970s), the Bayview-Leslie area (1970s to 1990s) and Thornhill (1970s to 1990s).

A pair of photos are offered, taken from an identical location — Bathurst, looking north from Drewry — in 1958 and again in 1999; obviously, there’s a world of difference between the two. For Torontonians of a certain age, the book is certain to bring back memories and stories of the rugged pioneering days of yesteryear. ♦

© 1999