William E. Dodd, the United States’ newly appointed ambassador to Germany in 1933, was a Jeffersonian democrat, a history professor working on a volume on the old American South, and a Sunday farmer with old-fashioned values who seemed so out of step with his new posting that one magazine called him “a square academic peg in a round diplomatic hole.”

William E. Dodd, the United States’ newly appointed ambassador to Germany in 1933, was a Jeffersonian democrat, a history professor working on a volume on the old American South, and a Sunday farmer with old-fashioned values who seemed so out of step with his new posting that one magazine called him “a square academic peg in a round diplomatic hole.”

While Dodd had his opponents in the State Department, he enjoyed the confidence of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and so moved with his wife and two grown children, Martha and Bill, into a stately mansion at 27A Tiergartenstrasse to serve as the American representative to Berlin in the early days of Hitler’s Third Reich.

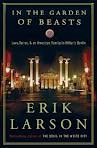

In The Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin (Crown) is author Erik Larson’s gripping and remarkably full account of the Dodd’s

time in Berlin as they came to know Germany’s heart of darkness. It is a story of naïve innocents who repeatedly fail to comprehend — but ultimately discover to their horror — that the “new Germany” was not the exciting, attractive, socially progressive place that it initially seemed, but rather a vicious totalitarian regime descending into barbarism.

Finding rich veins of material in Dodd’s archival papers, Martha’s memoir and diverse other sources, Larson spotlights the activities of the hapless ambassador and his daughter in alternating chapters. Dodd at first optimistically attempts to spread American values and appease Hitler’s unquenchable wrath, even going so far as to assert that the United States, too, has a Jewish problem of its own. (Indeed, some State Department bureaucrats felt the embassy had too many Jews on its payroll for the Nazis’ liking.)

Martha, recently separated from her American husband, engages in a series of ill-advised affairs under the embassy roof, some consummated in the library because of its comfortable couch. One liaison involves Rudolf Diels, the scar-faced chief of the Gestapo; a more prolonged romance involves Boris Winogradov, an official of the Soviet embassy. “This was not a house, but a house of ill repute,” the Dodds’ butler would observe. At one point Martha is even set up for a date (in a public bar) with Hitler, who kisses her hand. Hitler up close has a weak and soft face with pouches under the eyes, Martha would record, but his eyes “were startling and unforgettable . . . intense, unwavering, hypnotic.”

Hitler, Goebbels and other high-ranking Nazis delighted in deceiving gullible diplomats like Dodds, assuring them they sought only peace even as they built up what was by far the biggest standing army in Europe.

All Germans, but not foreigners, were required to give the “Heil Hitler!” salute to passing stormtroopers on parade. When Dodd complained that stormtroopers had roughed up some visiting Americans who pretended to windowshop rather than salute, he was easily mollified by Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels’ explanation that such incidents were being greatly exaggerated in the Jewish-controlled press. But attacks against visiting Americans, like those against Jews, only grew in number.

One day at a parade in Nuremberg, Martha witnessed stormtroopers drag a woman through the street as punishment for being betrothed to a Jew. Her hair shorn, her face and head covered with white powder, she wore a placard that said I HAVE OFFERED MYSELF TO A JEW. Afterwards, Martha persisted in giving the Nazis the benefit of the doubt. Their movement had a rosy-cheeked freshness about it that she found irresistible; she was enthralled with the new Germany and remained blind to its menace even as it manifested itself before her eyes. “The excitement of the people was contagious and I ‘heiled’ as vigorously as any Nazi,” she would write.

Dodd finally understood that the land of Goethe and Beethoven had reverted to some bestial primeval stage of civilization and that Hitler’s government was “nothing but a horde of criminals and cowards.” The rose-coloured spectacles were finally knocked from Martha’s eyes when an internal power struggle within the Gestapo forced her friend, the Mephistolean Diels, to flee for his life. She was afterwards so terror stricken that she begged her mother to sleep in the same room with her.

The so-called Night of the Long Knives, a purge that saw countless party insiders and opponents murdered as enemies of the Reich, only deepened the family’s revulsion; many of the victims had attended the Dodds’ soirees at the embassy. Afterwards a new phrase made the rounds in Berlin: “Lebst du noch?” “Are you still among the living?”

In October 1933 Dodd courageously gave a speech to the American Chamber of Commerce in Berlin that, using historical examples but not mentioning Germany, warned of the danger of “arbitrary and minority government.” He was widely applauded but the State Department rebuked him because, as a privileged guest in Germany, he was not supposed to make even veiled criticism of his hosts. Later he went on holiday rather than attend — and thus lend credibility to — a big Nazi rally in Nuremberg. The State Department sent another representative to the rally.

Dodd further rankles his Washington colleagues by declaring he will not attend another of Hitler’s speeches and never again invite a high-ranking Nazi to the Embassy. “What in the world is the use of having an ambassador who refuses to speak to the government to which he is accredited?” one wrote. Removed from his position in 1937, Dodd afterwards spoke plainly about the Nazi’s plain to take over Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia, and of the Fuhrer’s plan to exterminate the Jewish people.

Readers of one of Larson’s previous nonfiction books — The Devil in the White City — were introduced to a mass murderer who operated at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. In the Garden of Beasts is even more chilling because it reveals the dark soul of not just one but a whole nation of psychopathic murderers whose demonic rampage would destroy Europe and leave it strewn with millions of dead. ♦

© 2011 by Bill Gladstone