Wallace Shawn is known to many for his roles in movies like My Dinner With Andre (which he co-wrote), The Princess Bride and several Woody Allen films. He is also an avant-garde playwright whose latest work The Designated Mourner (Noonday Press, $14) opened in London last year and has been made into a film starring Mike Nichols.

Wallace Shawn is known to many for his roles in movies like My Dinner With Andre (which he co-wrote), The Princess Bride and several Woody Allen films. He is also an avant-garde playwright whose latest work The Designated Mourner (Noonday Press, $14) opened in London last year and has been made into a film starring Mike Nichols.

Interviewed on stage by Toronto actor Clare Coulter, the curmudgeonly actor-writer admitted that when he works, “I don’t start with the idea and then write the piece — first I write and then I have the idea.”

Shawn’s plays often confront painfully difficult and ugly elements of the human condition. While many critics have been perplexed and disgruntled by them in the past, some are now starting to react with favor, even excitement, according to Shawn. The New Yorker, for instance, said The Designated Mourner “has all the markings of a theatrical breakthrough.”

“At first my writing got almost entirely bad reviews, and the second time out it was almost the same, and it kept being like that,” he said, adding that something happens when playwrights stick with their chosen craft and don’t give up.

“After a long time almost everybody begins to think, ‘Why is he still around? There’s got to be something there.’ Some critics called (my play) The Fever ‘ridiculous garbage’ 10 years ago, and now they’re saying it’s ‘a fine master work.'” ♦

© 2001

* * *

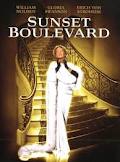

Sun Rises on Sunset Boulevard: As the Billy Wilder-Andrew Lloyd Webber confection Sunset Boulevard opens in North York, courtesy of Livent Entertainment, it is fitting to recall that Wilder, born in Vienna in 1906, was one of the fabled Jews who invented Hollywood. Wilder established his box-office credentials through such masterful and memorable works as Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), The Seven Year Itch (1955), Some Like It Hot (1959), The Apartment (1960) and of course Sunset Boulevard (1950). According to the New York Times, the elderly writer-director was “delighted” when Lloyd Webber’s stage version of the film noir classic opened in Los Angeles two years ago.

Sun Rises on Sunset Boulevard: As the Billy Wilder-Andrew Lloyd Webber confection Sunset Boulevard opens in North York, courtesy of Livent Entertainment, it is fitting to recall that Wilder, born in Vienna in 1906, was one of the fabled Jews who invented Hollywood. Wilder established his box-office credentials through such masterful and memorable works as Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), The Seven Year Itch (1955), Some Like It Hot (1959), The Apartment (1960) and of course Sunset Boulevard (1950). According to the New York Times, the elderly writer-director was “delighted” when Lloyd Webber’s stage version of the film noir classic opened in Los Angeles two years ago.

“In the beginning, I was afraid they’d completely reverse the whole thing. But they didn’t. In fact, I told them maybe they stuck too close to the screenplay. Maybe they should have moved a little farther away from it.”

Sunset Boulevard tells the story of Norma Desmond, a dethroned movie queen who tries to make a comeback to the big screen and encounters tragedy. The film, which opened at New York’s Radio City Music Hall in August 1950, received rave reviews and grossed $166,000 the first week, then a record high. So far, Livent’s production has not inspired accolades. But the theatrical megaspectacle has had a history of drawing popular acclaim without critical acclaim. Despite mixed reception by drama critics in both London and Los Angeles, it has enjoyed profitable runs in both cities. ♦

* * *

A Theatre Goes Dark: Just one month ago, this column conveyed the happy news that the Leah Posluns Theatre’s upcoming season, its 18th, would be highlighted by such potential winners as Twilight of The Golds, Broadway Bound and Yiddle With A Fiddle. However, the number 18, which traditionally symbolizes chai, or life, has in this instance brought an unexpected death.

Late in August, in a bid to rescue the Jewish Community Centre of Toronto from insolvency, the Jewish Federation of Greater Toronto abruptly brought down the curtain on the theatre, closed the theatre school, changed the locks on the doors, and handed pink slips to some 31 JCC employees. At present, the theatre is dark, silent, and entirely without life; a place, seemingly, where only ghosts walk.

But the JCC 31 apparently have no intention of going gently into that good night. When the Federation launched its UJA campaign at the Inn on the Park, they haunted the sidewalk outside, waving placards with messages like “If This Is A Rescue, Then Let Us Drown!”

Like a congregation of ghosts, they appeared again with friends and supporters on a sidewalk outside the JCC on Sept. 11 (the UJA’s Super Sunday), carrying placards, handing out leaflets, and listening as sympathetic performers like Salome Bey sang on their behalf. Reva Stern, the theatre’s former artistic director, helped direct this street production; Laura Martin, the former publicist, helped attract reporters from the CBC, CFTO, The CJN and other media; and the theatre’s former technical director helped set up the performers’ equipment. Meanwhile, groups of protestors were chanting “Save Our Theatre!” as they marched back and forth along the boulevard and along a short stretch of Bathurst Street.

Stern told this reporter that she felt the federation had disposed of the theatre staff as a homeowner might dispose of raccoons found in the attic – by trapping them, then summarily dumping and abandoning them in the wilderness. “I’ve worked here for 20 years,” she said.

“I put the first shovel into the ground for this theatre, and I’m not going away so easily.”

She said she recently attended a meeting of the Association of Jewish Theatres in Detroit. where directors of many smaller Jewish theatres across the continent approached her for advice. “We were the largest one, the one to whom the others looked for guidance: we were the beacon. Now I’m getting phone calls from them — they can’t believe what’s happened.”

The loss of this theatre is obviously a major blow to the Jewish-Canadian cultural community. Stern said that it will directly affect the sense of Jewish identity felt by the many Jews who attended the theatre religiously but were otherwise uninvolved with Jewish affairs. “The federation talks about the need for Jewish continuity, so how can it turn around and do a thing like this?”

Other placards were quite succinct in their astonished anger, asking only “How?” and “Why?” One senses there is another act to this unfolding drama, one that may contain some important disclosures. All that’s fully clear at this point is that this matter is terribly sad for all of us, especially the JCC 31 – and sadder still that it came just before and during the annual Days of Awe. ♦

©