A historical puzzle: Why did Goldwin Smith, the foremost literary personality of 19th-century English Canada and a notorious anti-semite, attend the opening of Toronto’s Holy Blossom Temple on Bond Street in 1897? And why, despite his outspoken enmity towards the Jews, did he contribute to the Holy Blossom’s building fund, as congregational records show?

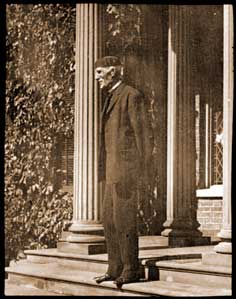

If Smith’s achievements as a pre-eminent man of letters are beyond question, so too are his credentials as a Jew-hater. Born in Britain in 1823, he received an impeccable Victorian education that included Greek and Latin. As an Oxford professor in the 1850s, he won acclaim for championing major university reforms and thereafter participated fully in the country’s political and literary life. In Toronto in 1875, he married the widow Harriet Boulton and moved into the Grange, the city’s most venerable address, where he lived until his death in 1910.

Nicknamed the “sage of the Grange”, Smith wrote on many public issues for many local newspapers and journals; and his byline was equally well known in New York and London. He was “the dominant intellectual force in the city for 40 years,” writes Greg Gatenby in Toronto: A Literary Guide.

Smith’s numerous articles on “the Jewish Question” include an essay by that title that appeared in the North American Review in August 1881, as a wave of anti-Jewish violence was sweeping across Russia.

Smith described the pogroms as both justified and inevitable. He presented himself as a tolerant liberal who felt compelled to condemn a singularly objectionable and “parasitic” race. He wrote as if everything he knew about the Jews had come from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Without paying more attention to his opinions than they merit, we must still be grateful to him for inspiring the powerful and thoughtful response to them, by one Isaac Besht Bendavid, that appeared in the North American Review in September 1881.

The pseudonymous Bendavid wielded his pen like a skilled swordsman. He refuted each of Smith’s main points so adeptly that he must have left readers wondering, “Who is this masked man?” even as he receded like an elegant Jewish Zorro into the mists of history.

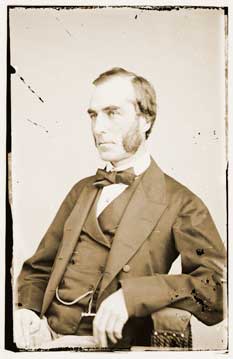

Smith’s animosity towards the Jews was likely inflamed by a deeply-felt literary jibe he had received from Benjamin Disraeli, Britain’s distinguished novel-writing Prime Minister.

Disraeli, who had been born Jewish but had converted, had ridiculed Smith in Lothair, his roman-a-clef novel of 1871. Lothair presented a fictitious, ridiculous Oxford professor, described as a “wild man of the cloisters” and a “social parasite”; the identification with Smith was widespread. Smith retained a lifelong grudge against Disraeli, and apparently railed often and bitterly against him, even long his death.

No matter how nicely expressed, Smith’s opinions on many subjects were often contentious; for instance, his support for the annexation of Canada to the United States. Like many people in that era, he seemed to view history as a series of defining contests between races; he was convinced that the political union of “the two English-speaking races” of North America was both mutually advantageous and inevitable.

Outwardly cold, he was often characterized as a lonely and angry man, all brain and no heart. Yet his servants adored him and observed that he would cheerfully take a hard seat rather than disturb a kitten asleep on his favourite armchair. He also marched under Protestant banners in Orange Day parades and was plainly prejudiced against Catholics, yet he supported the St. Paul de Vincent society, a Catholic charity. He was a man of contradictions. ♦

© 2004