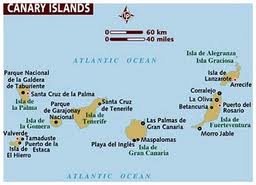

Back about 1890, Anglo-Jewish historian Lucien Wolf noted a curious fact: several of the first Jews to resettle in London after the Jews were re-admitted into England in 1655 had “hailed from a little archipelago in the East Atlantic, which had never before figured in Jewish history, and which, so far as I know, has not even yet found a place in that record.”

Back about 1890, Anglo-Jewish historian Lucien Wolf noted a curious fact: several of the first Jews to resettle in London after the Jews were re-admitted into England in 1655 had “hailed from a little archipelago in the East Atlantic, which had never before figured in Jewish history, and which, so far as I know, has not even yet found a place in that record.”

Intrigued by this significant historical puzzle, Wolf planned to visit the Canary Islands in 1894 but canceled his trip when, by a fortuitous coincidence, he found that the English Marquess of Bute had acquired 76 volumes of the very papers that he was determined to see.

The records of the Canariote Inquisition provide a gold mine of details about the small, obscure community of crypto-Jews, never numbering more than 400, that had been persecuted by the Catholic Church for three centuries. Essentially, the records document the Church’s attempt to seek out secret Jews, sorcerers and other heretics in the Canary Islands between 1499 and 1818. Wolf studied the papers meticulously for three decades, eventually extracting the Jewish cases and publishing them in English translation with a luminous scholarly introduction. The book, Jews in the Canary Islands, appeared under the auspices of the Jewish Historical Society of England in 1926. Recently the University of Toronto Press republished it as part of a series of rare and worthy historical reprints.

As Wolf explains, the records offer a lurid chronicle of the Inquisition’s iron grip on the so-called “New Christians” who practised Judaism in secret. Many had escaped to these remote islands from Spain and Portugal after 1492, but some, including a family named Beltran, had arrived in the 1480s or earlier.

Up to 1505, and for intermittent periods thereafter, the Conversos on the Canaries had “easily relapsed into their old Jewish life,” Wolf writes. They prospered as merchants, professionals, landowners, silversmiths, butchers and other tradesmen.

But when the anti-Jewish mania reached hysterical pitch, a wave of denunciations led to arrests, torture, trials and auto-da-fe’s in which Jews were burnt alive, often on the most flimsy evidence imaginable. In 1506, for example, one Marcos Goncales was denounced for washing shirts on Saturday night and hanging them out to dry on Sunday morning. Children confessed under torture that their parents spoke Hebrew and did not cross themselves in prayer.

Ship captains were warned, upon penalty of excommunication and loss of their ships, not to give passage to the heretics: the Church wanted them destroyed. Even so, many managed to flee to Madeira, Flanders, the West Indies, even Palestine (1524).

Ship captains were warned, upon penalty of excommunication and loss of their ships, not to give passage to the heretics: the Church wanted them destroyed. Even so, many managed to flee to Madeira, Flanders, the West Indies, even Palestine (1524).

In 1662, a long series of denunciations by Gaspar de Perera provided “a remarkably vivid picture of Marrano life” throughout Western Europe, Wolf relates. An “alleged Judaiser,” de Perera provided more than 20 “spy” reports on the London Jewish community, naming officials and describing “their social life, their political status, and even their personal appearance.” He also named the founders of Dublin’s Jewish community, who are otherwise unknown to historians.

It is, perhaps, a classic case of something good coming out of something bad. Wolf laments that an even more detailed set of records, known as Causas, was destroyed when Spain’s Inquisitorial Office finally shut down in 1818: the Causas contained elaborate genealogical evidence that had been gathered for many crypto-Jewish prisoners, as well as verbatim transcripts of their cross-examinations and trials.

Still, for all it does contain, The Jews in the Canary Islands is a remarkable historical document. Seventy-five years after its first appearance, the U of T Press deserves praise for making it accessible again. ♦

© 2002