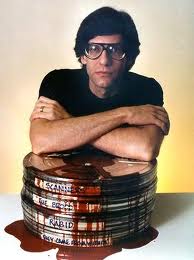

Twenty years ago this summer (i.e., the summer of 1974) this reporter was a 20-year-old film student at York University, who had been lucky enough to find some meager employment as a pre-production assistant for a $180,000-budget feature film being shot in Montreal. The working title was Orgy of the Blood Parasites, the director was David Cronenberg, and one of the co-producers was Ivan Reitman.

Twenty years ago this summer (i.e., the summer of 1974) this reporter was a 20-year-old film student at York University, who had been lucky enough to find some meager employment as a pre-production assistant for a $180,000-budget feature film being shot in Montreal. The working title was Orgy of the Blood Parasites, the director was David Cronenberg, and one of the co-producers was Ivan Reitman.

Although it eventually earned about $5 million, the film did not achieve any great fame or popularity in Canada, neither under its original name nor under its subsequent title of Shivers; in fact, it garnered some famously scathing reviews. Cronenberg and Reitman, however, independently went on to achieve astonishing successes as director and producer, respectively, of many box-office smashes. Cronenberg has attained critical respect and a wide cult following as a horror-fantasy film director whose films — M. Butterfly, Naked Lunch, The Fly, The Dead Zone, Dead Ringers, among others — have been screened around the world. Reitman, meanwhile, has produced some of Hollywood’s biggest box-office draws — Animal House, Stripes, Ghostbusters, Meatballs, et al.

I had worked with Cronenberg as a production assistant on a film in Toronto in 1973 — finding him highly intelligent, genial, sensitive and gifted — and he had allowed that I might work with him again in Montreal. When I first arrived, he put me up in his apartment on Nun’s Island for a few nights. I still have vivid memories of the aquatic bloodsucking leech that he kept in suspended animation in a waterfilled mayonnaise jar in his fridge. This repugnant wormlike creature was apparently his pet. He seemed to take great pleasure in bringing it to room temperature and, as it would begin to strive hungrily for nourishment, in feeding it bloody pieces of raw liver fresh from the butcher. He asked me to care for this thing while he went to Los Angeles, and left me the script of Blood Parasites to read.

Later, he seemed not to mind when, in answer to his direct questions, I confessed that I wasn’t crazy about the script — I found it exploitative, lurid and depraved. My naive youthfulness had blinded me into presuming that such frank admissions were permissable between friends. And they were: Cronenberg was easy-going, hardly the egomaniacal type. But he reported my opinion to Reitman, with whom it apparently raised doubts (as Cronenberg later told me) as to my continued employability beyond pre-production. Eventually, Reitman callously outlined why he was reluctant to hire me during production — my French wasn’t good enough, I was too fat, etcetera — so I returned home to Toronto. Thus ended my own cinematic career.

A flashback of this interlude from half a lifetime ago ran through my mind recently after I perused a highly interesting and detailed new biography of the director whose career course has far surpassed even the optimistic prognostications of his numerous boosters of two decades ago. David Cronenberg: A Delicate Balance (ECW Press, $14.95), by York University film instructor Peter Morris, is a finely researched, comprehensive study of the life and works of the controversial auteur whom some consider a genius in the Hitchcockian mode, responsible for some of the big screen’s most horrifying images. Others, however, regard his movies (especially the earlier ones) as grotesque and repulsive.

As Morris’s book carefully chronicles, the negative critical reception to Shivers nearly ruined Cronenberg. In a review in Saturday Night, entitled “You Should Know How Bad This Film Is — After All, You Paid For It,” critic Robert Fulford argued that the film displayed such atrocious bad taste that it was indefensible that some $75,000 in public funds had been invested in its production. Evidently, Cronenberg’s landlady eventually evicted him from his apartment on the strength of what Fulford had written, setting in motion a Kafkaesque nightmare for him.

Cronenberg’s initial reaction to the Fulford piece was placid acceptance, but he eventually came to resent it bitterly, as he explained in an article in The Globe and Mail. He also wrote that he realized that he was not exempt “from the fabled insecurity of the artist, the seer, the prophet, the Jew, the alien who can live happily in someone else’s house or country only until he is … recognized. Then it’s the knock on the door in the middle of the night.”

Fans of Cronenberg or the cinematic horror genre should find this book worth reading. Readers of this column may also find two other recent titles from ECW Press of interest. They are Leonard Cohen: A Life in Art, by Ira Nadel, and Mina’s Story: A Doctor’s Memoir of the Holocaust, by Dr. Mina Deutsch. ♦

© 1994