“Justice, justice, shall you pursue.” — Deut. 16:20.

“Justice, justice, shall you pursue.” — Deut. 16:20.

Ten years after it opened, Israel’s magnificent Supreme Court building still embodies the ideals of a just and humanitarian democratic society, and still remains what my guide, Amir Orly, calls “the pearl of Israeli architecture.”

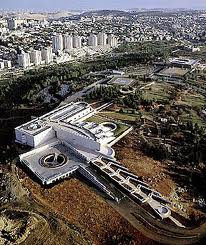

The structure sits in an exclusive and stately setting in central Jerusalem, on the Israeli equivalent to America’s Capitol Hill. In a straight line to the south, there’s a clear view of the boxlike Knesset: the brother-and-sister team of architects, Ram Karmi and Ada Karmi-Melamede, were intent on highlighting the direct connection between the place where legislation is enacted and the place where it is carried out.

Other buildings in the vicinity include the Prime Minister’s Office, a new Foreign Affairs building, and offices for the environment, health, treasury, social affairs and other ministries. Also close by is the Bank of Israel, which Amir compares to America’s Federal Reserve. “It’s built like the Israeli economy,” he jokes. “It’s an inverted pyramid with too many managers and not enough workers.” Yet another impressive neighbour is the Israel Museum, which he considers a smallish counterpart to Washington’s Smithsonian Institute.

Despite its bureaucratic function, the Supreme Court building seems refreshingly light, spare and pleasing. We approach along a promenade through an exotic garden featuring olive, cyprus and pomegranate trees as well as lavender, rosemary, hadas and other herbs that are representative of King Solomon’s Song of Songs.

The sidewalk narrows — as does, supposedly, the paths of justice. Amir points out the building’s contrast of shapes, straight and round: justice is circular, to be forever pursued and never fully attained, he explains, whereas the law is supposedly straight and strict. The architecture alludes to a line from the Psalms, “He leads me in the circles of justice.”

The sidewalk narrows — as does, supposedly, the paths of justice. Amir points out the building’s contrast of shapes, straight and round: justice is circular, to be forever pursued and never fully attained, he explains, whereas the law is supposedly straight and strict. The architecture alludes to a line from the Psalms, “He leads me in the circles of justice.”

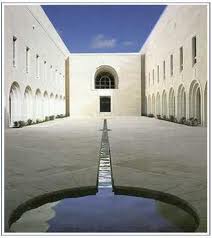

Other contrasts abound. There are two kinds of stone, the pure smooth white stone associated with Tel Aviv and the rough-hewn old creamy limestone associated with Jerusalem and, in fact, known as Jerusalem stone. There is also the lively dialogue between old and new that you sense everywhere in Israel. “This is a young country, but the Jewish people is a very old people with roots deep in the ground,” is how Amir puts it.

The promenade continues indoors, lined by streetlights as though we were still outdoors; the brilliant interplay of outer and inner elements is a symbolic attempt to integrate the court with the society that built it. Likewise, the five courtrooms are usually flooded with daylight “so you feel you are partly outside even when you are inside.” No dark, obscure, oppressively heavy Kafkaesque halls of justice here.

There are cloistered courtyards, elegant domes, and familiar references to ancients tombs, temples, gates, archways, towers and walls. Yet despite its complexity, the architecture seems transparently pure and spiritually uplifting. It’s poetry in stone.

The building has three levels: the criminals come from below, the judges from above, the public via the promenade on the middle level. “The idea is that everyone meets in the centre,” Amir says. The middle level also features a glorious panoramic view of Jerusalem, in part so the judges never lose sight of the city and its populace.

Nothing quite like the Israeli Supreme Court building could exist in Baghdad, Beijing, Havana, Moscow or any other capital of a repressive regime. For that matter the building, with its playful homage to a range of regional architectural styles from the Herodian era to the period of the British Mandate, could not have been built in any place except Jerusalem.

Nothing quite like the Israeli Supreme Court building could exist in Baghdad, Beijing, Havana, Moscow or any other capital of a repressive regime. For that matter the building, with its playful homage to a range of regional architectural styles from the Herodian era to the period of the British Mandate, could not have been built in any place except Jerusalem.

Arguably as unique and contextually appropriate as the Temple of olden times, the Israeli Supreme Court is a triumphant architectural embrace of the ideals of democratic humanism by an ancient-modern people whose reverence for justice and jurisprudence is but one of many gifts it has given to Mankind. ♦

ISRAEL’S SUPREME COURT BUILDING

The new home of Israel’s Supreme Court is a magnificent light-filled stone and glass architectural gem that perfectly complements the description of Jerusalem as “a city of stone, possessed by light and obsessed with its past.”

Designed by Israeli architects Ram Karmi and Ada Karmi-Melamede and completed in 1992, the building makes reference to a vast range of regional architectural styles — Herodian, Hellenistic, Crusader, Greek Orthodox — from ancient times right up to the British Mandate period. It is a complex and breathtaking structure built out of contrasts: light and shade, wide and narrow, open and closed, stone and plaster, straight and curved.

The architects, who are sister and brother, knew the building had to reflect Jerusalem. They spoke with jurists, historians and philosophers, and immersed themselves in local architectural traditions and styles. Not surprisingly, the Bible was a primary influence. During their research they discovered that law was referred to as a “direct path” which they interpreted as a straight line. The curve, circle and half-circle represents justice. This came from Psalm 23 where one of the verses is translated as “He leads me in the circles of justice.” The end result reflects justice, truth, mercy and compassion.

Like much else in Israel, the building owes its existence to the generosity of the Rothschild family. In 1984 Dorothy de Rothschild — widow of James Rothschild, who had funded construction of the Knesset, the Israeli Parliament — decided to fulfil her late husband’s wish to fund construction of a Supreme Court building. She requested (not demanded) several conditions: that the building be constructed on a site across from the Knesset; that local materials be used as much as possible; and that the name Rothschild not appear on the building (a tradition the Rothschild Foundation, Yad HaNadiv, maintains for all of its philanthropic work in Israel). She also requested that the cost of the 22,000-sq.-metre building never be revealed and that it be maintained in the same condition as when handed to the State. The Government has respected all of these conditions from the moment construction started in 1988.

Since its opening, the Supreme Court building has become a popular attraction for tourists, and on average more than 4,000 visitors pass through its security gates each day. The building houses five courtrooms, a library, and chambers for the justices.

From above the main staircase, natural light filters down from a large curved window, creating an outdoors effect. This window provides a sensational panoramic view of the city, old and new. Walking up the staircase is much like strolling in a street in the old city but enhanced with modern lampposts. The limestone wall beside the stairs represents the Western Wall. As with the old Wall, there’s an illusion that there isn’t any cement holding these bricks, which are secured from behind with stainless steel rods and cement.

The five courtrooms also feature natural light streaming down from skylights. They are smaller than one might expect; they variously seat from 40 to 150 people. The Justices enter from a room above, the prisoners by private elevator from below, and the public from the main floor. Once everyone is assembled the symbolism is that all are equal before the law and therefore meet on equal ground.

Located near the Knesset on Kiryat David Ben Gurion, the Supreme Court Building is open Sunday to Thursday 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Guided tours are offered in English every day at 12 noon. ♦