Born as Tsvi Hirsh Glicenstein in Konin Poland about 1872, my great-grandfather came to London as a youth, married, then brought his family to New York in 1909, and to Toronto in 1913.

Born as Tsvi Hirsh Glicenstein in Konin Poland about 1872, my great-grandfather came to London as a youth, married, then brought his family to New York in 1909, and to Toronto in 1913.

His tombstone (1955) memorializes Harris Glickstein, the anglicized name he used most of his life. My late grandfather Ralph Gladstone further altered the surname in order to find work in a city where Jews were quietly excluded from various professions, businesses, neighborhoods and public beaches.

Russell Gladstone, my father, was the eldest of nine children, including several writers and educators and a professional sculptor. A talented Sunday painter, he would have been amazed to learn that an internationally renowned Jewish sculptor named Chanoch Glicenstein came from Turek, a town not 30 kilometres from Konin.

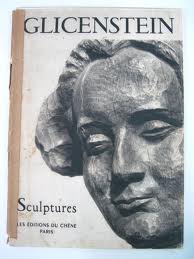

Chanoch Glicenstein died on December 28, 1942 — 60 years ago — after being struck by a cab near his home in the New York City borough of Queens. He was 72 years old and at the top of his artistic powers.

Chanoch Glicenstein died on December 28, 1942 — 60 years ago — after being struck by a cab near his home in the New York City borough of Queens. He was 72 years old and at the top of his artistic powers.

Was he related to the Glicensteins of nearby Konin? The rarity of the name and other compelling evidence suggests a connection. At the very least he was a contemporary of my great-grandfather and their paths could have crossed various times in various places.

In any event, the 60th anniversary of his death is occasion enough to recall his life and works. Born in 1870, Chanoch was the son of a pious cutter of tombstones who wanted him to become a rabbi. Alas, his son left the yeshivah at 13 to sell his carvings from village to village.

In Lodz, his slate chess figurines made a sensation, prompting a patron to send him to an academy in Munich. Exhibiting in Berlin, Venice, London, Brussels, he rose to international prominence, twice winning the coveted Prix de Rome. At the Paris Exposition of 1900, his statue “Cain and Abel” won a gold medal and his exhilarating “Messiah” was exhibited with works by August Rodin at the latter’s request.

Settling with his family in Rome, he took on the name Enrico Glicenstein.

In 1928 Mussolini sat for a bust and asked the sculptor if he was a Fascist. Answering in the negative, Glicenstein knew that his days in Italy were numbered; that year, he and his family emigrated to America. When Italy adopted many anti-Semitic laws in the late 1930s, he returned his knighthood to the Italian government in protest.

His clients included ambassadors, bankers, cardinals, kings and presidents. Besides Mussolini, famous and infamous heads that Glicenstein sculpted included those of Roosevelt, Einstein, d’Annunzio, Pope Pius, King Victor Emanuel, Hindenburg, Paderewski, Admiral Byrd, Lord Balfour and Israel Zangwill. He also made three-dimensional studies of Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and Walt Whitman, and various paintings, drawings and etchings.

He was known for simple sweeping lines, a preference for Biblical subjects, and a bold economic use of the sculptural medium in works like “Moses,” “Queen Esther,” “Soldier Carrying a Wounded Comrade,” “Lamentations of a Ghetto Child” and “Spanish Loyalist Woman.” He treated wood as a living and sacred thing, studying the block until he perceived the form imbedded within. “The harder the wood the better,” his son, the late artist Emanuel Romano, once explained. “Father wanted to feel the struggle against his chisel as he worked to liberate the figure that his mind envisioned in the wood.”

He was known for simple sweeping lines, a preference for Biblical subjects, and a bold economic use of the sculptural medium in works like “Moses,” “Queen Esther,” “Soldier Carrying a Wounded Comrade,” “Lamentations of a Ghetto Child” and “Spanish Loyalist Woman.” He treated wood as a living and sacred thing, studying the block until he perceived the form imbedded within. “The harder the wood the better,” his son, the late artist Emanuel Romano, once explained. “Father wanted to feel the struggle against his chisel as he worked to liberate the figure that his mind envisioned in the wood.”

He left a widow, a married daughter and son, but no grandchildren; his art resides in major museums and institutions in the United States, Europe and Israel. The Israel Bible Museum in Safad, formerly the Glicenstein Museum, holds many of his works. Unfairly, he never gained the recognition in America that he enjoyed in Europe, and nearly 70 years after his death his name seems almost unknown even among Jewish patrons of the arts.

* * *

Indeed, the name Glicenstein was unknown to me until I discovered some 15 or 20 years ago that it was my own ancestral name. That knowledge opened the door to significant genealogical progress. Gaining access to 19th-century Jewish birth, marriage and death records from Konin, I was able to reconstruct an elaborate Glicenstein family tree going back more than two centuries.

Next I began to search out living Glicensteins with the help of book and newspaper references and organizations like Yad Vashem and the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors. My inquiries produced a pile of responses with postmarks from London, Paris, Sao Paulo, Jerusalem, New York, California and other places.

Astonishingly, every one of the dozens of Glicenstein families I have encountered so far can be traced back to several Polish villages — Konin, Turek, Dobra, Wladyslawowie — all within 30 kilometres of each other. Imagine, if you will, a sort of linear diaspora along which various Glicensteins settled, some even relocating as far as Kalisz and Lodz, perhaps a full day’s carriage ride away.

Several of my correspondents have informed me of a family tradition that all Glicensteins are related. I located Mrs. Jacqueline Wolf (nee Glicenstein) of Long Island, as well as her younger sister Jocette, after reading her moving Holocaust memoir, Take Care of Jocette! (Those were her father’s last words to her.) Like numerous other Glicenstein families, they went from Poland to France but still found themselves caught in the Nazi dragnet. “My father once told me, ‘If you happen to meet a Glicenstein, he has to be a relative because anyone with that name is related to you, so be nice to them,'” Jacqueline told me.

Rabbi Abraham Chanoch Glitzenstein of Jerusalem wrote in Hebrew: “From my father I heard that in all the world there is only one family named Glicenstein.” A prolific author of books on religious subjects whose grandfather was the shoichet in Turek, he wrote again after reviewing my research: “I am well and truly convinced that this is one family.”

Joseph Palmer (Glicenstein) of California, a great-nephew of Chanoch Glicenstein, wrote that the sculptor “visited our house in Kalisz in 1915 and drew me in my swaddling clothes.” He and his brothers all became artists, he said.

Theodore Richmond of London, an ex-Koniner who is writing a book about the town, provided what so far is the most important circumstantial evidence linking my family to the sculptor. He wrote that Chanoch Glicenstein, a friend of his grandfather’s, had “often visited Konin and (was almost certainly) related to the family of the same name in Konin.”

Although my research to date has been unable to furnish links between these various “branches,” it has served to dispel some misconceptions. Born in 1953 to Canadian-born parents, I grew up with the illusion that our family had been among the lucky ones to have escaped the Shoah. Of course, for most Jewish families, nothing could be further from the truth. Published after the war, the Konin Yizkor (Memorial) Book records that at least one Glicenstein family from Konin was destroyed. A book of Jews deported from France to Nazi concentration camps lists 16 Glicensteins, all originally Polish. And Yad Vashem has informed me of 189 Glicensteins in its files who perished.

Does the discovery of a possible familial link to a once-famous personage help or hinder genealogical research? In my opinion, both. On the one hand, it provides a tremendous impetus and interest factor. On the other hand, it provides a temptation to indulge in wishful thinking that may obscure the truth.

No connection can be claimed without documentation from a reliable source. Unfortunately, some 19th-century Jewish records from Poland have not survived and others are hard to access from North America. Solving this mystery will be trickier than I thought. It will certainly involve much more research and perhaps even travel to Poland. Having started this work, I feel obliged to continue, especially as I now sense the encouragement of many people, both living and dead. ♦

© 2002