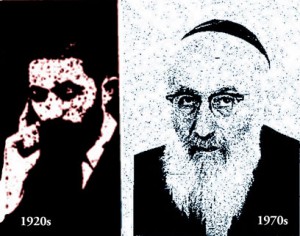

Rabbi Israel Levi Hurwitz was born in Grodno province of Lithuania in 1893, the son of Simon Aaron and Chaya Hurwitz. He was educated in the Novogrodok and other yeshivot. He was active in Vilna as an orator and became a “shaliach” to Canada for a yeshivah in Hebron, Eretz Israel. In 1933, according to the book Prominent Jews of Canada (the source of these early details), he was rabbi of Beth Israel, the Shaw Street Synagogue in Toronto, and founder of the Chevra Mikra. He died in May 1979 and soon afterwards J. B. Salsberg wrote a column in his memory in the Canadian Jewish News (June 7) from which these details have been abstracted:

Rabbi Israel Levi Hurwitz was born in Grodno province of Lithuania in 1893, the son of Simon Aaron and Chaya Hurwitz. He was educated in the Novogrodok and other yeshivot. He was active in Vilna as an orator and became a “shaliach” to Canada for a yeshivah in Hebron, Eretz Israel. In 1933, according to the book Prominent Jews of Canada (the source of these early details), he was rabbi of Beth Israel, the Shaw Street Synagogue in Toronto, and founder of the Chevra Mikra. He died in May 1979 and soon afterwards J. B. Salsberg wrote a column in his memory in the Canadian Jewish News (June 7) from which these details have been abstracted:

Salsberg said he was shocked that the passing of Rabbi Israel Hurwitz did not receive notice on the front, or even interior, pages of our major Jewish newspapers; he found out about it from the bulletin of the Shaarei Shomayim synagogue.

“Rabbi Hurwitz was never attached to, nor was he ever the spokesman for any of the well-defined sectors of religious Jewry,” Salsberg wrote. “He was not attached to any of the prestigious synagogues. But his voice was always clear and unafraid. He never sought to please and was, therefore, often controversial.”

However, he always headed his own congregation. He may have headed various of the old downtown synagogues at one time or another, but he was always head of his own small group who joined him at his own private residence.

A product of the Musar yeshivot of Lithuania and White Russia whose emphasis was on the moral and ethical precepts of Judaism, Rabbi Hurwitz came here in the 1920s to collect money for one such academy. He gave voice to his beliefs at small study classes in his own chapel; in small synagogues and even at Shaarei Shomayim in its early days; in sermons; and in funerals where he delivered the eulogies.

Because Salsberg believed and worked strongly for social justice, Rabbi Hurwitz felt a kinship with him and the two came to be friends who “saw each other as travelers on the same road.” Salsberg used to visit him in his home, but always took care to come only at night “to shield him from unprincipled criticism from the camp of the unwashed politicians. . . and . . . Yahoos.”

Salsberg recalled that he would park his car some distance away from his Augusta Avenue home and walk towards it, where he would be greeted by the rabbi and his saintly wife.

“We would seat ourselves in the chapel (I usually brought my own yarmulke), his wife would bring tea, lemon and ‘eingemachts’ (jam) and we would literally revel in meaningful conversation for hours. He knew that I held the Musar movement in highest regard and that pleased him, of course.”

Once, while the two were discussing a somewhat extremist wing of Chassidism, Rabbi Hurwitz paraphrased a statement of one of the pillars of the modern Musar movement, and Salsberg thought the remark very meaningful. Rabbi Hurwitz said:

“They are so concerned with saving someone else’s soul that they are ready to kill in their effort; at the same time they are even more concerned with their own stomachs and general well-being. But we say that they should be more concerned with the other person’s stomachs and well-being and pay more attention to their own souls.”

May his memory be for a blessing. ♦