From the Globe and Mail, February 2002

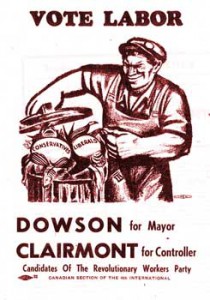

As a Trotskyite and leader of the Revolutionary Workers Party, Ross Dowson might have been expected to tarry on the fringes of Canadian political life forever, so it came as a considerable shock to many Torontonians when he drew twenty per cent of the vote in a mayor’s race in 1947.

As a Trotskyite and leader of the Revolutionary Workers Party, Ross Dowson might have been expected to tarry on the fringes of Canadian political life forever, so it came as a considerable shock to many Torontonians when he drew twenty per cent of the vote in a mayor’s race in 1947.

Dowson, who died February 17 [2002] at the age of 84, never again approached that respectable showing in several subsequent municipal and federal elections. Still, he managed to make a significant mark on the Canadian political scene from the sidelines, in part by being a thorn in the side of the establishment, a role he evidently cherished.

Regarded by associates as a keen political strategist, he devised a popular protest slogan — “End Canada’s Complicity in the War in Vietnam” — that helped shape the national antiwar movement of the 1960s.

In the 1970s, he initiated a high-profile court battle against the RCMP for labeling him a “subversive,” which he lost after a flurry of motions, counter motions and appeals that lasted seven years. But his evidence before two federal commissions into RCMP wrongdoings in the 1980s was instrumental in the eventual replacement of the RCMP’s security service with a civilian agency.

Yearning to bring his socialist ideals to the masses, he forged an alliance between his leftist League for Socialist Action and the NDP’s radical youth wing, the Waffle. Even though he was a lifelong devotee of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky, he was a “homespun revolutionary,” said his “comrade,” Harry Kopyto, a legal agent.

“If you want to know the secret of Ross Dowson, you won’t find it in Russia, you’ll find it in southern Ontario,” Kopyto said. “Ross was totally Canadian. There was nothing foreign about him.”

He was born in 1917 — “a rather prophetic year,” observed his sister, Lois Bedard — as the third of seven children in a working-class family in the Toronto suburb of Weston. His father was a printer from whom Ross acquired useful rotogravuric skills; an anarchist sympathizer and atheist who encouraged his children to think and act independently. An older brother, Murray, took Ross to CCF and Trotskyist meetings during the Depression and honed his political debating skills. Ross formed a political club named after Spartacus, the leader of a slave rebellion in the ancient Roman Empire, and distributed pamphlets, joined May Day marches, and spoke at open-air meetings.

“He got his politics from the hungry Thirties, seeing working-class people share what they had while the upper class kept what they had to themselves,” Kopyto said. “He believed in the social ownership and democratic control of the wealth of society.”

When Earl Birney resigned as leader of the Canadian Trotskyist faction in 1939 to concentrate on being a poet, Dowson stepped into the gap. A high school graduate who read voraciously, he was thrown suddenly into a sophisticated and chaotic milieu of politics, culture and ideas originating from a diverse range of people of Jewish, Ukrainian and other immigrant working-class backgrounds.

When Earl Birney resigned as leader of the Canadian Trotskyist faction in 1939 to concentrate on being a poet, Dowson stepped into the gap. A high school graduate who read voraciously, he was thrown suddenly into a sophisticated and chaotic milieu of politics, culture and ideas originating from a diverse range of people of Jewish, Ukrainian and other immigrant working-class backgrounds.

Although disgusted by the “capitalist war machine,” Dowson served in the Armed Forces, though never overseas; for a time he was a combat training officer at Camp Borden, Ont. At war’s end in 1945, he was again disgusted at seeing Canadian troops being put to work on the docks and railways, and in brick-yards, foundries and packing plants: the government was attempting to get the peacetime economy rolling again, but Dowson saw it as scab labour and an abuse comparable to those of Hitler’s Germany.

Screaming at the top of his lungs, he urged mass resistance, but he alone resisted. He was arrested and paraded back to camp under armed guard.

Dowson had a talent for reducing complex ideas to their essence, Kopyto said. In his first mayoralty campaign, for instance, he printed a pamphlet with a drawing of “a muscular man, sleeves rolled up, using a broom to sweep out the corridors of city hall — sweeping away bankers in their black suits with dollar signs on their clothes.” The pamphlet was distributed to tens of thousands of homes in Toronto, with the result that “one in five Torontonians voted for Ross,” Kopyto said.

A publisher of many radical pamphlets as well as The Workers Vanguard and other newspapers, Dowson ran bookstores on Queen Street West and elsewhere that were each the focal point of a lively intellectual circle. “We talked about art, revolution, science, we’d show movies — there was even a drama group,” Kopyto said. “It was a large and vibrant movement.”

Among those interested, apparently, were RCMP operatives who spied on its members for years, and eventually accrued a 2,000-page file on Dowson. They allegedly infiltrated the Socialist League and spread damaging secrets about Dowson and his associates; he blamed them for its break-up in the mid-1970s.

To Trotskyists, Dowson’s greatest accomplishment may have been his successful 1963 initiative to repair an historic rift in the movement, known as the Fourth International. Despite his reputation as a revolutionary, he was very much a “creature of habit,” Kopyto said. “He’d always close the bookstore at 6 o’clock, go to the restaurant next door at 6.05, and eat a hot hamburger with mashed potatoes. He was very regular in his habits. He’d always go to bed at the same time. He was a man of total discipline.”

From the late 1960s through the late 1980s, he occupied a tiny apartment on Homewood Avenue that was cluttered with books, newspapers, journals and other paraphernalia. As he was entirely devoted to the revolution, he never married, but remained the center of a coterie of comrades who considered him a brilliant mentor.

“He was asked once why he was prepared to make such a great personal sacrifice, and he said it wasn’t a sacrifice, it was a labour of love,” said his friend. Gordon Doctorow, a teacher. “He did it because he took pleasure in writing and organizing and promoting the socialist ideals. He didn’t think it was a sacrifice, he thought it was an amazing opportunity.”

A debilitating stroke put him in the hospital in 1989 and he remained hospitalized, semi-paralyzed and hardly able to talk, for the rest of his life. “He was a very sensitive gentleman,” said Bedard. “Many of his opponents would say, ‘Well, Ross, I don’t agree with you, but you’re really challenging and you’re really a gentleman.'” He is survived by sisters Lois Bedard and Margaret Joyce Rosenthal.

* Ross Jewitt Dowson, Canadian revolutionary, born Toronto, September 4, 1917; died Toronto, February 17, 2002. ♦

© 2002, 2013