From the Canadian Jewish News, January 2013

From the Canadian Jewish News, January 2013

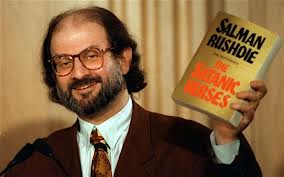

London-based writer Salman Rushdie was happy to sell his novel The Satanic Verses to Viking Penguin in February 1988. But six months after the novel appeared, the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against him for his blasphemous insult “against Islam, the Prophet and the Qur’an.” Instantly he became a hunted fugitive — just the sort of nightmarish turn one might expect from a good film noir.

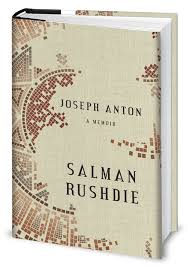

As in a film noir, many of Rushdie’s friends deserted him and multitudes of people blamed him for being too free with his artistic expression. Having “vanished onto the front page,” as writer Martin Amis put it, he withstood 13 years in hiding, and eventually discovered how to reclaim his liberty. Joseph Anton, a record of his life “on the lam,” takes its title from the pseudonym he used during that time in homage to writers Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov.

An article in the Indian newspaper India Today “was the match that lit the fire,” Rushdie recalls. After riots in the streets left dozens dead, The Satanic Verses was banned in India; then the great mullah issued the fatwa. Soon afterwards, his wife called and said: “Don’t come back here. There are 200 journalists on the sidewalk waiting for you.” Thus began his life on the run.

There were real and tangible threats against Rushdie even in Great Britain. Muslim citizens in London and Bradford held mass demonstrations, burned his novel and openly called for his death. Fortunately, Scotland Yard offered him and his family a series of safe houses as well as safe cars with drivers. Deeply offended that the Brits would dare protect the apostate, Iran severed diplomatic relations; Britain retaliated in kind.

Islamic rage and menace seemed uncontainable. One day Rushdie and his driver were stuck in traffic outside the Regent’s Park Mosque as the faithful were pouring out of Friday afternoon prayers. “I assume the doors are locked?” he asked, hiding behind his newspaper. There was a click. “They are now,” the driver replied. Some British Muslims actually tried to sue Rushdie for blasphemy and the judge received some threatening letters before duly throwing the case out of court.

Islamic rage and menace seemed uncontainable. One day Rushdie and his driver were stuck in traffic outside the Regent’s Park Mosque as the faithful were pouring out of Friday afternoon prayers. “I assume the doors are locked?” he asked, hiding behind his newspaper. There was a click. “They are now,” the driver replied. Some British Muslims actually tried to sue Rushdie for blasphemy and the judge received some threatening letters before duly throwing the case out of court.

In America, the blind sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman (later jailed for the first World Trade Center attack) complained that if Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz had been properly punished for his book Children of Gebelawi, then Rushdie would not have dared to publish The Satanic Verses. Soon afterwards the elderly Mahfouz, a Nobel prize winner, was stabbed in the neck; he survived.

Even while safe in hiding, Rushdie still felt the sting of many knives in his back. British Foreign Secretary characterized him as a great defamer and writer Roald Dahl called him “a dangerous opportunist.” The Daily Mail called him “bad-mannered, sullen, graceless, silly, curmudgeonly, unattractive, small-minded, arrogant and egocentric.”

In a pithy exchange of letters with Rushdie in The Guardian, writer John le Carre faulted him and made it seem he deserved everything he was getting and more. “There is no law in life or nature that says great religions may be insulted with impunity,” le Carre wrote.

In reply, Rushdie defended his book and refuted the notion “that anyone who displeases philistine, reductionist, radical Islamist folk loses his right to live in safety.” After le Carre expressed concern for the safety of the publishing and bookshop staff handling The Satanic Verses, Rushdie replied that “these were the people . . . who have most passionately supported and defended my right to publish. It is ignoble of le Carre to use them as an argument for censorship when they have so courageously stood up for freedom.”

Seeming to bend over backwards for the sake of reconciliation, the Pope, the archbishop of Canterbury, the cardinal of New York, the British chief rabbi and many others expressed understanding for the ayatollah’s feelings. For a time Rushdie also tried a conciliatory approach, saying he was seeking “common ground” with those whom his book had offended — but it felt false. Later he reverted to standing up for freedom of expression, realizing he could not abandon his own cherished values.

While many people were cowed into silence by the vociferous threats of the Islamists, some defended Rushdie nobly and acted towards him with astonishing generosity, selflessness and courage, he writes.

Bloodthirsty Islamists ultimately murdered the Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses; they also stabbed the Italian translator and shot the Norwegian publisher but both recovered. Although Rushdie was never physically harmed, the added stress broke up his marriage and dramatically curtailed his freedom to live freely, travel, attend public events, and see his son.

An important turning point occurred when Scotland Yard seemed to deny him permission to attend an important literary event where he was to receive an award. “You are endangering the citizenry of London by reason of your desire for self-aggrandizement,” an agent told him.

For Rushdie, it was a moment of truth: he knew he had to act assertively to regain his life. He calmly explained that he knew where the Dorchester Hotel was and had money for a taxi. “So the question is not whether or not I’m going to the awards. I am going to the awards. The only question you have to answer is, are you coming with me?” Thenceforth Scotland Yard assigned a new senior officer to his case and he was allowed much more latitude to make occasional surprise appearances in public. Although the fatwa is permanent and may not be lifted, moderates in Iran eventually acted to neutralize it as best they could.

A thorough telling of Rushdie’s years in hiding — which he relates in the second person, referring to himself as “he” — Joseph Anton is a great book despite being overlong and overly detailed. At its heart is a clear and essential moral that reflects one of the most important themes of our time: liberty and freedom of expression are universal human rights, not Western cultural values alien to the cultures of the East. Another important message: bad things happen when good people stand by and do nothing.

Cultural relativists, apologists for Islamic extremism, and anyone who has ever used the deceitful neologism “Islamophobia” — a word that Rushdie defines as a means “to help the blind remain blind” — won’t like this book. The rest of us should cheer. ♦