From the Canadian Jewish News, October 2012

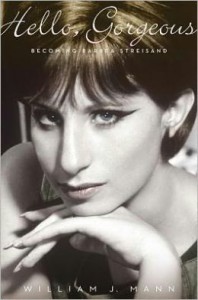

As legions of Barbra Streisand fans pay exorbitant prices (reportedly up to $500) for tickets to see her during her latest (and perhaps last) world tour — which includes a concert at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre on Oct. 23rd 2012 — it seems a fortuitous time for the release of Hello Gorgeous, William J. Mann’s new 500-page opus about the iconic performer who has won two Academy Awards and nearly every other major award that show business offers.

As legions of Barbra Streisand fans pay exorbitant prices (reportedly up to $500) for tickets to see her during her latest (and perhaps last) world tour — which includes a concert at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre on Oct. 23rd 2012 — it seems a fortuitous time for the release of Hello Gorgeous, William J. Mann’s new 500-page opus about the iconic performer who has won two Academy Awards and nearly every other major award that show business offers.

Surprisingly, considering its heft, Hello Gorgeous isn’t a full biography: it covers only the first five years of Streisand’s career, chronicling her ascendancy from her first stage appearances in 1960 as a brash, nervous, gawky 17-year-old from Brooklyn to her decisive Broadway triumph in the musical Funny Girl. The title comes from Streisand’s memorable opening line in Funny Girl, when she comes on stage, takes a long look in a mirror, and says to herself, “Hello, gorgeous.”

Mann tells us that Streisand had adored her father, who had died when she was very young, and grew up starved for affection and approval from her hard-to-please mother; and so sought affection and approval from audiences. One of her first gigs involved a talent contest in a small Manhattan nightclub. There was a vulnerability about the homely girl in front of the microphone that made the audience root for her. “The room had exploded into cheers for her, and she won the contest,” Mann writes, describing a scene that would become familiar. An early boyfriend who’d helped expand her initially tiny repertoire noted how her eyes and face would come alive with every ovation, illuminated by “an electric look generated by the power of the applause.”

In order to be mesmerizing on stage, Streisand had learned early on that she had to be an actor as well as a singer, injecting songs with as much emotion, pathos, or sex appeal as they seemed to require. For a song like Cry Me A River, for example, she made it about her relationship with the above-mentioned boyfriend which ended badly. “The pros are talking about a rising new star on the local scene,” critic Dorothy Kilgallen wrote. “Eighteen-year-old Barbra Streisand never had a singing lesson in her life, doesn’t know how to walk, dress, or take a bow, but she projects well enough to bring the house down.”

Coached by a coterie of show-biz veterans, Streisand painstakingly weaved together a stage persona using definitive elements of Audrey Hepburn, Mae West, Billie Holiday, Judy Garland and, yes, Fannie Brice. Indeed, Streisand shared a basic and inescapable feature with Brice — a funny-looking nose. Her famous decision not to have it fixed was a reflection of her constant determination to be taken for who she was, and on her own terms. Her crooked nose became as strong an emblem of her individuality as the unique spelling of her first name: she had dropped the usual middle A from Barbara soon after winning the talent contest.

At 19 she made her Broadway debut in the Harold Rome musical I Can Get It For You Wholesale, based on the 1937 Jerome Weidman novel. She garnered raves for her supporting role as Miss Marmelstein, a spinsterish secretary who comes rolling out in her office chair, kvetching in song about how no one addresses her intimately by her first name or by an affectionate pet name. The New York Times gave the show a positive review and singled out Streisand, describing her as “the evening’s find . . . a girl with an oafish expression, a loud irascible voice and an arpeggiated laugh. Miss Streisand is a natural comedienne.”

As the number and range of her television spots, nightclub gigs and recording sessions grew, so did her salary, and Streisand, in this period, took her own apartment for the first time; she had previously been living like a nomad in borrowed rooms and temporary sublets. She also became romantically involved with the show’s male lead, Elliott Gould, whom she would marry. (As her career rose meteorically and his tanked, the marriage quickly fell apart.) She also acquired a manager, an agent and other assorted professional handlers.

Film producer Ray Stark, son-in-law of the legendary Fannie Brice, wanted to produce a Broadway musical called Funny Girl about Brice’s stormy marriage to gambler Nick Arnstein. Streisand was desperate for the lead, believing it would push her over the cusp to stardom. Other contenders for the part included Anne Bancroft, Carole Burnett, Eydie Gorme and Judy Holliday.

As Mann notes, she had a natural resemblance to Brice that tipped the scales in her favour. “The ‘angular young girl with the nose of an eagle, slightly out-of-focus eyes and a mouth engaged in a battle with a wad of gum’ [as one reporter had described her] could just as easily have been Fanny Brice as Barbra Streisand.” But she tried to enhance the similarities whenever she could. In her various television appearances and interviews, she became as Brice-like as possible in order to improve her chances for the role.

Streisand won the part, of course but, ironically, by the time she was playing it she was as much playing herself more than anyone, since the role was crafted around her own oversized public persona as much as it was around Brice. The lyrics, too, often seemed to describe Streisand’s own temperament, as in: “I’m the greatest star, I am by far, but no one knows it.”

Interestingly, not all of Streisand’s instincts proved sound. For example, she initially didn’t want to sing two songs in Funny Girl that she didn’t think were right for her — “People” and “Don’t Rain On My Parade” — both of which ended up being among her most identifiable signature tunes.

Mann does not overlook Streisand’s less attractive qualities — she was often demanding and was famously narcissistic — but still Hello, Gorgeous reads like hagiography. There’s as much here, I suppose, as most people will ever want to know about Streisand’s early years. Even those who don’t count themselves as fans (myself included) may still be intrigued by this well-researched, novelized account of an ugly duckling turned swan with the magical ability to rouse audiences into sustained and rapturous applause. It’s a quintessential show-business tale. ♦