From the Canadian Jewish News, Summer 2013

From the Canadian Jewish News, Summer 2013

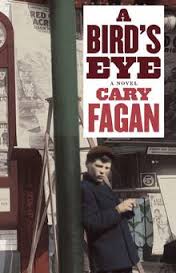

With his latest novel A Bird’s Eye, prolific Toronto writer Cary Fagan has created what may be his best work since his acclaimed first novel, The Animals’ Waltz, won the Canadian Jewish Fiction Prize in 1994.

A Bird’s Eye marks a return for Fagan to the small-canvas, miniature novelistic form that he utilized so masterfully in his 1996 work The Doctor’s House, in which chapters were often less than one page long and the story progressed through well chosen minimalistic detail and ellipsis. Although the story is not nearly as ambitious, A Bird’s Eye also reminds me of E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime in its use of immigrants as central characters set apart from the landed gentry.

A captivating coming-of-age story set in Toronto of the 1920s and 1930s, A Bird’s Eye focuses on young protagonist Benjamin Kleeman who, as a first-person narrator, deftly pulls back the curtain on many scenes he could not have witnessed himself. Ben strives to learn the craft of magic, and the illusory narrative tricks that he employs in telling his story seems in keeping with the sleight-of-hand and trompe-d’oeil that he will employ on stage.

Ben is the son of a failed Jewish tinkerer-inventor father, Jacob Kleeman, and an Italian mother, Bella, born with a large birthmark on her face. In his one heroic act, Jacob rescues the despondent Bella from jumping off the Toronto Island ferry. The two strangers, unable to communicate in words, disembark and make passionate love in an abandoned warehouse.

Fagan’s painterly prose records: “Their moans were fragments of lost language rising into the air, heard distantly by a night watchman at a coal depot who paused in the lighting of his cigarette.” This particular chapter, reminiscent of David Copperfield, is titled “I Am Conceived.”

Again reminiscent of Dickens, 14-year-old Ben walks restlessly through the streets of Toronto in the wee hours of the morning. One night he is beaten up by thugs and is rescued by a 16-year-old Negro girl, Corinne Foster, who scares off his attackers.

“She was the first coloured person I had ever met, and I could not stop stealing glances at her whenever we passed under a street lamp. We walked down Albany Avenue to Bloor Street and sat on the steps of Trinity United Church and watched a Weston Bakery van go slowly by.” Ben enters his first love affair, which progresses nicely until nearly the end of the novel.

Jacob, Ben’s father, is a schlemiel whose brother Hayim steals his one good practical invention, a design for a new fountain pen, and grows rich on it. Jacob is meanwhile being cuckolded by the family’s German boarder, a painter of miniatures, who is having an affair right under his nose with his wife, Bella.

When Jacob gets a job with Might’s directories, he enumerates city households and records the details using a Kleeman pen. Even Ben cannot escape the fact that his father is a nebbish. The only time Ben is truly impressed with him is when he discovers him cheating at cards. “I felt myself almost giddy with the excitement of his getting away with it . . . . There was an elegance to it, the small moves of the hand, shifting away the attention. It was the most impressive thing I’d ever seen my father do.”

When Jacob gets a job with Might’s directories, he enumerates city households and records the details using a Kleeman pen. Even Ben cannot escape the fact that his father is a nebbish. The only time Ben is truly impressed with him is when he discovers him cheating at cards. “I felt myself almost giddy with the excitement of his getting away with it . . . . There was an elegance to it, the small moves of the hand, shifting away the attention. It was the most impressive thing I’d ever seen my father do.”

When Ben goes with his father to synagogue, he is impressed by the magic and transcendance on display. “We stood at the back and I watched the men sway, stoop-shouldered. I couldn’t resist the strange effect of the chanting, how it turned these salesmen and shopkeepers into something that felt holy. What was it? The room, the atmosphere, the sound, the silk and the embroidered letters, the lighting. A powerful effect causing a certain trick of the heart, that’s what caught my attention. And afterwards, I knew, they would once more turn back into salesmen and shopkeepers.”

It is Ben’s progress as a magician that is the novel’s main concern. He studies magic books, finds mentors, practices constantly, and is eventually hired to perform on stage. The story culminates in a stylized piece of stage magic that seems to symbolize the narrator’s growth and transcendance over his mundane circumstances, his emergence through magical means as a victor rather than a victim.

As a subplot, Hayim uses his bankroll to arrange a match between his clubfooted sister Hannah and a wealthy Gentile industrialist who breaks off the engagement on the belief that his fiancee, being Jewish, has a cloven hoof and is a secret disciple of the devil. Resigned to her fate as a spinster, Hannah glumly sells her engagement ring and — in the year 1938 — buys a ticket back to Poland. Here, as elsewhere, the irony is understated.

I’ve admired Cary Fagan’s literary craftmanship, both in long form and in short stories, ever since taking a creative writing workshop with him some 16 years ago. He’s flirted with magic before — for instance in “The Floating Wife,” one of the pieces in his most recent book of stories, My Life Among the Apes — but never to such good effect.

A Bird’s Eye provides us with a lovingly rendered minimalist portrait of Toronto in the 1930s. Happily, Fagan abandons the bleak, sprawling north-Toronto cityscapes featured in a few of his previous novels. Those previous books include Felix Roth (1999), The Mermaid of Paris (2003) and Valentine’s Fall (2010). He has also written several story collections and more than a dozen children’s books — the latest of which is “Oy, Feh, So,” with National Post illustrator Gary Clement.

Like much of what Fagan writes, A Bird’s Eye has an organic theme and plot that are not overreaching: Fagan paints in an understated way, with small, even brush strokes. In my opinion A Bird’s Eye, with its trim and finely balanced prose, diverse mix of ethnic characters, fine sense of place and storyline that glides along as smoothly as a bird in flight, ranks as perhaps his finest book yet. (House of Anansi Press) ♦