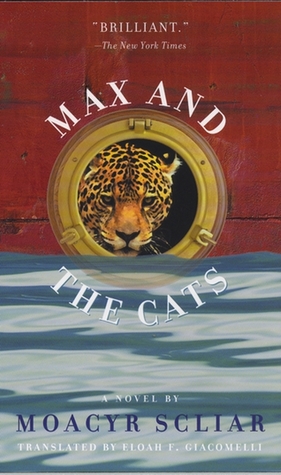

Brazilian writer Moacyr Scliar, who died earlier this year at the age of 73, was a proponent of “magic realism,” a category of fiction prevalent among South American writers and especially evident in two of Scliar’s best known novels, Max And The Cats (1981) and The Centaur In The Garden (1984).

Brazilian writer Moacyr Scliar, who died earlier this year at the age of 73, was a proponent of “magic realism,” a category of fiction prevalent among South American writers and especially evident in two of Scliar’s best known novels, Max And The Cats (1981) and The Centaur In The Garden (1984).

As it happens, the phrase “magic realism” aptly describes something that happened to me recently. Walking home from synagogue, I got into a conversation with a friend about Max and the Cats. When I admitted I had never read the copy on my bookshelf, my friend urged me to read it that very day, saying it would require only a couple of hours.

At home, as I opened the book for a cosy read, something fell out of its middle: five pages of my handwritten notes from an interview I had evidently conducted with Scliar in 2003 during the International Authors Festival in Toronto. I was astonished: had I really spoken with Scliar? How could I have forgotten about it?

Reading the interview felt strangely like getting a personalized preface to a book from a writer situated beyond the grave. Even so, Scliar was articulate, lively and thoughtful. When I got to reading Max and the Cats, it seemed similarly robust with Jewish concerns and pulsating with vibrant, albeit nervous, life.

Max, the novel’s central character, is forced to escape Berlin in the late 1930s after his affair with a married woman is discovered. His steamship sinks in mid-ocean, however, and he shares a lifeboat with a jaguar, who stares menacingly at him but mysteriously forebears from eating him. Paralyzed with fear, Max catches fish to keep both himself and the jaguar alive.

Eventually the lifeboat reaches the shores of Brazil, the jaguar bounds into the forest, and Max is rescued, ultimately supposing the cat may have been a hallucination. But the various Nazis that turn up in postwar Brazil are no hallucination and no less threatening than the jaguar: they haunt his life and destroy his peace.

Scliar, a medical doctor who devoted all of his spare time to writing, was the son of immigrants from the Russian province of Bessarabia who came to South America during the period of Jewish mass migration a century ago. Unlike many writers within the tradition of magic realism, his use of its conventions was not meant as a political metaphor for snarling national dictators with sharp claws, but rather as a means to reflect upon the fearful and often paranoic modern Jewish sensibility.

Scliar, a medical doctor who devoted all of his spare time to writing, was the son of immigrants from the Russian province of Bessarabia who came to South America during the period of Jewish mass migration a century ago. Unlike many writers within the tradition of magic realism, his use of its conventions was not meant as a political metaphor for snarling national dictators with sharp claws, but rather as a means to reflect upon the fearful and often paranoic modern Jewish sensibility.

The Centaur in the Garden focused on a man who has a double identity as a centaur, very much like the Jew in Brazilian society, Scliar told me. “In your home, with your Jewish meals, you follow your tradition, you keep Shabbat, and you speak Yiddish. When you go on the street, the language is different and the customs are different, and you feel divided. And this is not bad for writers. In my case it was a source of inspiration.”

Scliar and his wife and son lived in Porte Alegra, a city roughly the size of Toronto, where he said he felt comfortable living as a Jew within a tolerant society. “I am very proud to be Jewish,” he said, noting that only the week before he had been admitted into the Brazilian Academy of Letters, a prestigious cultural institution. “I said on that occasion that for me it was a great honour because I was there as a member of the Jewish community, as a writer of Jewish influence.”

His own literary influences included Sholem Aleichem, Y. L. Peretz and, as astute readers will quickly deduce, Franz Kafka. “Isaac Babel, the Russian novelist and short-story teller, is one of my favourites,” he said. “There are some stories of his that I’ve read at least 20 times.”

The main question I had for Scliar, and perhaps the very question that had brought him to Toronto, had to do with the similarity of the 2002 book Life of Pi to Max and the Cats, a situation that had generated a literary controversy. The commercially successful novel by Canadian writer Yann Martel had seemingly borrowed the central situation of a man and a great cat on a lifeboat from Max and the Cats.

Although Martel has always denied reading that novel before writing his own, Scliar said the duplication had troubled him. “I would prefer that the publicity came out of the novel itself. I’m a little bit sad because the publicity came from the scandal, which is the case with many Latin American authors. That is, you are noticed when there is something with a book, not the book itself — a political situation, or the writer is under arrest. I would prefer that the novel would be noticed because of the novel itself.”

Martel, who won the Man Booker Prize worth $75,000 for Life of Pi, has always claimed that he purposely avoided reading Max and the Cats because he wanted to lessen its influence on him; however, he admitted that he was “indebted to Mr. Moacyr Scliar for the spark of life” he had given Life of Pi.

Perhaps it’s a good thing that I put Max and the Cats aside in 2003, so that I could come back to it and read it now on its own terms, recognizing it as the fine and memorable short novel that it is. Let’s hope Scliar isn’t entirely overlooked next year when director Ang Lee’s film treatment of Life of Pi is due in theatres. ♦

© 2011