Eighteen-year-old Frank Westwood had gone out with friends about 7.30 that Saturday evening, October 6, 1894.

Eighteen-year-old Frank Westwood had gone out with friends about 7.30 that Saturday evening, October 6, 1894.

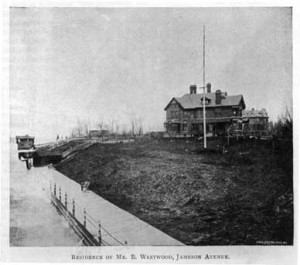

By the time he returned to his family’s Jameson Avenue mansion about 10:30, his father, sister and brother had already retired upstairs; his mother, seeing he was safely in, shortly went up, too, leaving him on the stairs. The lad was likewise in the process of retiring when the door-bell, which he alone heard, summoned him to a different fate. He relit the gas banquet-light and opened the door about fourteen inches, as far as the chain would allow, keeping his foot against it. On the platform he saw a young man with a thin moustache, wearing dark clothes and perhaps a fedora; he did not recognize the man, who was obscured in shadows. Wordlessly, the stranger shot him down.

Upstairs, his parents heard the singular report and the thud as their son hit the floor. “Mother, mother, I am shot,” he cried. They rushed downstairs to find the vestibule full of smoke and Frank lying across the step, bleeding profusely, a bullethole in his waistcoat. Quickly dressing and rushing outside with his own revolver in hand, Mr. Westwood saw no sign of a prowler. He fired a warning shot into the air in the hope that it would also summon the police. Mrs. Westwood telephoned for the doctor — Dr. Griffith — who pronounced Frank’s wounds to be serious: the bullet had entered his breast and been deflected into the liver and back muscles; it defied all attempts at extraction. By Monday, as Frank’s condition deteriorated, the Globe predicted: “It May Be Murder.”

Frank’s story never varied. Three days later, understanding that he was near death, he made a deposition swearing that he knew neither the identity nor the motive of his attacker. Having meditated on the affair, he thought that perhaps his nemesis had been a childhood antagonist, Gus Clarke, but detectives would later demonstrate this was mere conjecture.

The funeral ceremonies commenced at two o’clock on Friday October 12, with four clergy officiating; the family’s pastor, Rev. Dr. Scott, chose his text from Job 2:10 — “What? shall we receive good at the hands of God, and shall we not receive evil?” The grounds and the street outside the Westwood home were filled with family friends and morbid sightseers, according to the Toronto World. “Half the feminine population of Parkdale was present. Young girls, children and mothers of families who came with baby carriages waited in the melancholy drizzle to see the funeral procession.” It was nearly dark before the body was laid to rest at Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

The Parkdale Mystery, as the newspapers had dubbed it, clearly had the local constabulary stumped. The case was less than one week old when the zealous editors of the World conceived of a brilliant ploy that would win them a prized, albeit transitory, victory over their rivals in the perpetual game of one-upmanship that they played. The Parkdale Mystery clearly required the wits of a great detective: why not solicit the opinion of British writer Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the world-famous literary detective, Sherlock Holmes? Doyle was due in Toronto for a speaking engagement the following month. With all despatch, the World sent the known facts of the case to the highly popular author and awaited his response.

* * *

The shooting of Frank Westwood occurred at Lakeside Hall, his family mansion at 28 Jameson Avenue, in the west Toronto village of Parkdale. The inquest, which ran for many weeks, was like a game of nine-pins, according to the anonymous and poetic World scribe who covered it: “The detectives have cheerfully set up half a dozen theories and as cheerfully brought new witnesses to bowl them over.” While Sherlock Holmes might have seen right through the overlapping veils of diaphanous translucencies that made up the Parkdale Mystery and pronounced the whole matter to be “Elementary, my dear Watson,” the city’s finest detectives were finding the circumstances to be as opaque as, say, the thick curtains that draped the stage of the city’s treasured Grand Opera House.

The shooting of Frank Westwood occurred at Lakeside Hall, his family mansion at 28 Jameson Avenue, in the west Toronto village of Parkdale. The inquest, which ran for many weeks, was like a game of nine-pins, according to the anonymous and poetic World scribe who covered it: “The detectives have cheerfully set up half a dozen theories and as cheerfully brought new witnesses to bowl them over.” While Sherlock Holmes might have seen right through the overlapping veils of diaphanous translucencies that made up the Parkdale Mystery and pronounced the whole matter to be “Elementary, my dear Watson,” the city’s finest detectives were finding the circumstances to be as opaque as, say, the thick curtains that draped the stage of the city’s treasured Grand Opera House.

The opening of the inquest drew throngs of curious spectators, who surrounded Police Station No. 6 and spilled out into the street. “People of all ages and sexes struggled in the rain to secure admission, and the majority were disappointed in their efforts,” reported the World on October 13. At the inquest, which was later removed to Parkdale Town Hall, Frank Westwood’s parents again told their stories, most details of which had already been heard. Benjamin Westwood, a well-to-do sporting goods manufacturer and prominent member of the Parkdale Methodist Church, said that relations between himself and his son had been “the very pleasantest.” He acknowledged that he was rather strict in the management of his family and said the only trouble he had with Frank’s personal habits concerned his smoking, about which he had talked to him often. He said he knew of nothing in his own life nor in his son’s that would lead anybody to bear Frank ill will. He recalled that his son had painted his assailant as “medium height, moustache, middle-aged and dark clothing. He never gave a further description.”

“Did he ever say anything about how it all occurred?”

“Yes, he said that when he opened the door he saw the man standing there, and as soon as the door was wide open he was shot.”

“Did he tell you that he knew any man that could answer the description?”

“No.”

“Did he ever tell you anything that might throw light on the question?”

“No.”

“Did he mention any person who might have done it?”

“No. I asked him if he ever had a quarrel or if he thought of any person who might do it. He answered ‘No’ to all my questions.”

“Do you know anything whatever that might explain the shooting?”

“No. I have turned it over and over in my mind and to me it is a greater mystery than ever.”

Mrs. Westwood said she never knew Frank to have any troubles, small or great, nor had he kept company with any young ladies. She said that her son had a cheerful, kindly disposition, and had seemed happy and untroubled that night. His brother, eleven-year-old Willie Westwood said Frank sometimes frequented Dane’s boathouse, the headquarters of the “Maroons,” and had no girl friends to his knowledge. None of Frank’s friends could offer any evidence that there was a woman in the case. Other witnesses made a similarly chaste assessment of his social life. Dr. Lynd, one of several physicians who had attended to Frank’s wounds, recalled that he had described his assailant “as a low sized man, wearing dark clothes and a dark hat, and I understood him to say it was a young man with a thin mustache. He said it was done so quickly he hadn’t time to get a look at the man and did not recognize him.”

Some boys related that two strangers had inquired the location of the Westwood residence several hours before the shooting; these turned out to be piano movers. Several witnesses — Mrs. Card and her children, and the Misses Wesley — all claimed to have seen a man enter the Westwood grounds shortly before the shots were heard. Mrs. Card lived across the street but did not know Frank Westwood by sight. She swore that a gentlemen had stepped in front of her as she was getting off the King-street car from the Grand Opera House, and had walked down Jameson about ten feet ahead of her. The World summed up her testimony as follows: “The man was dressed in a light overcoat, gray or fawn; witness thought he wore a Christy stiff; he was a man of medium height; witness had a side view of his face at the corner of King and Jameson; he had pale sallow complexion, dark hair and was not more than twenty, and wore neither moustache nor whiskers. Witness would know him if she saw him again. Just before entering her gate she saw the same young man on the west side of the street in front of the Westwood place. She was certain it was the same man by his overcoat and carriage. She saw him turn into the Westwood’s little gate and stand under the trees.” This, it happens, is the most detailed description available not of the murderer but of the murder victim; Mrs. Card and the others had seen Frank Westwood, returning home.

Some boys related that two strangers had inquired the location of the Westwood residence several hours before the shooting; these turned out to be piano movers. Several witnesses — Mrs. Card and her children, and the Misses Wesley — all claimed to have seen a man enter the Westwood grounds shortly before the shots were heard. Mrs. Card lived across the street but did not know Frank Westwood by sight. She swore that a gentlemen had stepped in front of her as she was getting off the King-street car from the Grand Opera House, and had walked down Jameson about ten feet ahead of her. The World summed up her testimony as follows: “The man was dressed in a light overcoat, gray or fawn; witness thought he wore a Christy stiff; he was a man of medium height; witness had a side view of his face at the corner of King and Jameson; he had pale sallow complexion, dark hair and was not more than twenty, and wore neither moustache nor whiskers. Witness would know him if she saw him again. Just before entering her gate she saw the same young man on the west side of the street in front of the Westwood place. She was certain it was the same man by his overcoat and carriage. She saw him turn into the Westwood’s little gate and stand under the trees.” This, it happens, is the most detailed description available not of the murderer but of the murder victim; Mrs. Card and the others had seen Frank Westwood, returning home.

A gentleman known as W. H. Hornberry, evidently some sort of local sleuth whom the newspapers somewhat derisively referred to as “Parkdale’s Sherlock Holmes,” elicited hearty laughter from the public when he was called upon to testify. He said that he had combed the grounds after the tragedy, seeking clues, and had found a scrap of paper upon which was written, “If you do not — I will.” Clumsily and amateurishly, he had thrown this message away, he admitted. Hornberry also said that he had found another potentially revealing scrap of paper in nearby Victoria-crescent — which he had kept. “Amidst breathless suspense in the audience, the witness dived down in his overcoat pocket and produced a piece of foolscap, on which was glued his remarkable find,” the World reported. “Mr. Dewart [an attorney] looked at it and smiled. So did Hornberry until he saw Detective Porter pocket his precious clue.”

The inquest closed with an explicit admission of defeat. A fickle public, having resigned itself to the fact that the mystery would likely remain unsolved, transferred its morbid curiosity to other matters. On October 29, the World reported: Even Sherlock Holmes Is Puzzled by the Case. Dr. Doyle had sent a handwritten note to the paper from Chicago, which was reproduced in its entirety on the front page. “Dear Sir,” he wrote,

“I shall read the case, but you can realize how impossible it is for an outsider who is ignorant of local conditions to offer an opinion. Thanking you, I am, Faithfully Yours,

A. Conan Doyle.”

* * *

Details of the Listowel Horror were soon screaming across the front pages of the World, the Empire, the Mail, the Globe and other Toronto papers just as loudly as those of the Westwood case had done. On October 21, a thirteen-year-old girl, Jessie Keith, was brutally butchered to death and left naked in the bush. The conservative Mail said the atrocity “was on a par with the hideous Whitechapel murders” and ran this concise editorial note on October 23: “Shakespeare has said, ‘For murder, though it have no tongue, will speak with most miraculous organ.’ Parkdale and Listowel are impatiently waiting to hear it.” When a French-Canadian vagrant named Almeda Chattelle was apprehended for the killing several days later, the papers forthrightly speculated that he was Jack the Ripper, a suspicion that prompted police to send his picture to Scotland Yard. Indifferent to the right of a detained suspect to be considered innocent until proven guilty, the World’s reportage of the Listowel Horror reflected the highest level of public outrage. From the outset, it referred to the accused as “the fiend” and “the monster” in articles that ran beneath headings such as Under the Shadow of the Gallows, and On the Track of the Assassin. Detectives, careful to avoid a spontaneous lynching by an angry mob, moved the prisoner with extreme caution and discretion. Ultimately, the “beast’s” own confession secured both a courtroom conviction and a hangman’s noose around his neck.

By the time the celebrated creator of Sherlock Holmes had reached Toronto on November 26 to deliver a lecture at the newly-built Massey Hall, a startling and seemingly decisive development had again pushed the Westwood murder case onto the front page. Frank Westwood had speculated that his attacker might have been Gus Clarke, a street-wise associate in trouble with the law. The police had grilled Clarke extensively at the inquest and were satisfied of his innocence. In mid-November, they had questioned him again, this time outside the witness box, and had attained some additional facts and corroborative information. Their subsequent arrest of Clara Ford, whom common parlance of the day unabashedly defined as a mulatto tailoress, “came upon the city yesterday morning almost as unexpectedly as a lightning flash from a cloudless sky,” said the Globe on November 22.

By the time the celebrated creator of Sherlock Holmes had reached Toronto on November 26 to deliver a lecture at the newly-built Massey Hall, a startling and seemingly decisive development had again pushed the Westwood murder case onto the front page. Frank Westwood had speculated that his attacker might have been Gus Clarke, a street-wise associate in trouble with the law. The police had grilled Clarke extensively at the inquest and were satisfied of his innocence. In mid-November, they had questioned him again, this time outside the witness box, and had attained some additional facts and corroborative information. Their subsequent arrest of Clara Ford, whom common parlance of the day unabashedly defined as a mulatto tailoress, “came upon the city yesterday morning almost as unexpectedly as a lightning flash from a cloudless sky,” said the Globe on November 22.

Clara Ford has to be one of the most unusual and colourful figures to make an appearance in the annals of crime in Toronto. Born thirty-two years earlier in a house that stood on the site of what is now Old City Hall, she was adopted as a foundling and raised by one Mrs. Jessie McKay, who had died in the Home for Incurables only the previous March. Years earlier, she had been married in Chicago to a husband who thereupon deserted her. She possessed a cheap German revolver, of the type known as a bull-dog, and knew how to use it; the chambers showed evidence of having recently been fired, and test bullets fired from the weapon repeatedly bore the same pattern of striation as the bullet that had killed Frank Westwood. She frequently dressed in men’s clothing, and police had found a dark suit in the trunk in her room. She was rumoured to have posed as a choir-boy in church, as a constabulary detective, and as a male lecturer on socialist subjects. According to the Mail, she smoked, she shaved, she played the cornet and kettledrum, and she favoured literary works that treated of love and murder. She boarded at Mamie Dorsay’s house in York-street and sewed for Samuel Barnett, a Hebrew tailor; she had been arrested in his shop, near the corner of King and York streets. She evidently had no aversion to strong drink. In a previous employment waiting tables, she had displayed a volatile temper by drawing a razor in a dispute with a customer. Yet she was generally well-liked and had shared tales of her escapades with a wide circle of acquaintances. She had once lived on Jameson-avenue, and had become known by sight to many residents of Parkdale, including Frank Westwood; police found an old note she had written, which mentioned his name. If her dusky skin and wild pranks had previously lent her a certain renown in some parts of town, particularly among the “coloured people” of the Ward, that was nothing compared to her burgeoning infamy following her arrest. “A few days ago her exploits were known to a comparatively small circle,” reported the Mail. “To-day she sits perched upon a throne of notoriety, discussed by thousands of busy tongues.”

Detectives Slemin and Porter had picked her up on November 20. Sergeant Reburn had cloistered her in his office in police headquarters at about four o’clock, and told her she was suspected of a serious crime. “I know,” said she, “it is the Westwood murder.” He cautioned her numerous times in the ensuing interview that anything she might say could be used against her. At first, she had offered the alibi that she had been at the Toronto Opera House (the Grand) to see the nickel-and-dime melodrama, The Black Crook, with eight-year-old Florence McKay, whom Det. Porter immediately fetched from her place of employment at Mrs. Phyle’s boarding house on Jarvis-street. The waif had seemed eager to protect Clara Ford, but her answers, alas, did not support her alibi; tripped up, she eventually admitted that she and Clara had arranged to meet outside the theatre, but the latter had never showed. (Clara masked all details of her relationship to Florence, whom the papers later identified as her “putative” daughter.) Reburn asked Clara about the men’s clothes that were found in her room, and she said they were hers and had not been stolen; she had given her hat to a former landlady, Mrs. Mary Crozier, who was then fetched and questioned.

Reburn had no further conversation with his prime suspect until after she had been given supper. He went out from 6.30 to 7.15 p.m. Upon his return, he informed her of the holes that her two witnesses had put into her alibi, and that Mrs. Crozier swore she had seen a revolver in Ford’s pocket on the night of the Westwood murder. After a few more paltry attempts at denial, Clara Ford seemed to want to come clean. “There is no use my misleading you any longer in the matter,” she said. Reburn again cautioned her that anything she said could be used against her. But Clara Ford evidently possessed a wide streak of that murderer’s braggadocio that insists upon a full airing of the foul deed. “I shot Frank Westwood,” was how she began her dramatic confession, which poured from her lips until well past ten o’clock.

Reburn had no further conversation with his prime suspect until after she had been given supper. He went out from 6.30 to 7.15 p.m. Upon his return, he informed her of the holes that her two witnesses had put into her alibi, and that Mrs. Crozier swore she had seen a revolver in Ford’s pocket on the night of the Westwood murder. After a few more paltry attempts at denial, Clara Ford seemed to want to come clean. “There is no use my misleading you any longer in the matter,” she said. Reburn again cautioned her that anything she said could be used against her. But Clara Ford evidently possessed a wide streak of that murderer’s braggadocio that insists upon a full airing of the foul deed. “I shot Frank Westwood,” was how she began her dramatic confession, which poured from her lips until well past ten o’clock.

All these facts, narrated by Sgt. Reburn, came out at the preliminary hearing. Clara had admitted that she made up the theatre alibi as an excuse. She had said that Frank and the other boys had teased her about her colour in the summer, and that Frank had attempted to take undue liberties with her on Jameson-avenue. On the evening of October 6, wearing men’s clothing beneath her woman’s jacket and skirt, she had walked along King-street to Dufferin-street, down Dufferin-street to the corner of Dominion-street, and there removed her skirt and jacket and put them under the plank sidewalk. By he own admission, she had gone down Jameson past the crossing, had waited in the shadows, and had seen Frank Westwood come down the street, enter his gate, and go into his house. Reburn read her words verbatim from his notepad: “After he went in, I crowded through a picket fence at the foot of Jameson-avenue. Some of the pickets were missing. I walked along the wharf and round into Westwood’s place. I stood under a tree for about fifteen or twenty minutes. At the end of that time I went up the drive and rang the door-bell. There was a dim light in the hall, and Frank Westwood, in answer to the ring, came to the door. He opened the door and leaned out forward like this, and then I fired.”

Clara had confessed that she left the way she had come, retrieved and donned her jacket and skirt unseen, walked down to the wharf at the foot of Dufferin-street, and went underneath the wharf from west to east along the waterfront, through the old fort to the foot of Bathurst-street. She made it back to King-street, then York-street, then Mrs. Dorsay’s boarding house. According to Sgt. Reburn, she seemed sorry that she had killed her quarry, but said it was not right of a man to take advantage of a woman. Why hadn’t she taken immediate steps to stop his annoyances? “Well,” she had said, “you know my colour. I would have had no chance against a man like that in his position. … At that time I told him I’d get even with him and I have, and I suppose I’ll get life for it.”

As a precaution, Reburn said he had invited Inspector of Detectives Stark to hear part of Clara Ford’s confession — Reburn’s recitation of which, from his elaborate notes, now kept the overflowing courtroom transfixed for hours. There was a full parade of witnesses that day, including Florence McKay, Mrs. Crozier, Mrs. Phyle and others. The proceedings lasted five hours, throughout which Clara Ford sat, silent and almost motionless — “stoical as an Indian warrior at the torture stake,” offered the World. “When the young woman walked up the stairway into the dock every eye was upon her. Clara Ford met their gaze with an audacious daring, which was merely the unmasking of a strong soul in its despair. She wore over her black skirt and Eton jacket a beaver-trimmed jacket, and upon her head a fedora hat with a couple of feathers. It could easily be seen that she had a strong dash of negro blood in her, being probably a quadroon or nearer akin to the black. Her curved nose shows the white strain, while her restless eyes and sensuous mouth tell of her African origin….”

There was judged to be sufficient evidence to merit a trial. “I am guilty,” was how the accused boldly answered when asked how she intended to plead. The statement seemed to plunge her attorney, Mr. Johnston, into a state of apoplexy, however, whereupon the young lady, possessed of a highly refined knack for the theatrical, amended it accordingly to “I am not guilty.”

This was largely the state of affairs in regard to the Westwood case when Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle arrived in the sleepy provincial town of Toronto the Good. Fatigued after a long journey from Schenectady, N.Y., via Niagara Falls, he retired to the home of a friend, Dr. Latimer Pickering, at 281 Sherbourne-street. Hector Charlesworth, a reporter for the World, would recall in a volume of memoirs published in 1925 that Dr. Doyle “asked that a reporter be sent to him who could tell him all subsequent developments [in the Westwood case]. When I talked with him he laughingly said that he was the last man in the world to offer solutions in murder mysteries, because in the Sherlock Holmes stories he always had his solutions ready-made before he started to write and constructed his narratives backward from that point. He also said that fiction writers were not very good judges of evidence, because they were accustomed to create facts to suit themselves, whereas detectives had to take them as they were.”

This was largely the state of affairs in regard to the Westwood case when Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle arrived in the sleepy provincial town of Toronto the Good. Fatigued after a long journey from Schenectady, N.Y., via Niagara Falls, he retired to the home of a friend, Dr. Latimer Pickering, at 281 Sherbourne-street. Hector Charlesworth, a reporter for the World, would recall in a volume of memoirs published in 1925 that Dr. Doyle “asked that a reporter be sent to him who could tell him all subsequent developments [in the Westwood case]. When I talked with him he laughingly said that he was the last man in the world to offer solutions in murder mysteries, because in the Sherlock Holmes stories he always had his solutions ready-made before he started to write and constructed his narratives backward from that point. He also said that fiction writers were not very good judges of evidence, because they were accustomed to create facts to suit themselves, whereas detectives had to take them as they were.”

Dr. Doyle’s lecture at Massey Hall was well received. Afterwards, he spoke at length with reporters. Alas, he left to posterity only one remark that directly pertains to the Westwood case. It is the sort of non-committal comment that a prudent outsider might make, yet it possesses a vaguely prescient tag that seems to hint at the shocking conclusion of the case that would follow. “It is a strangely absorbing mystery, and I discussed it at length with my brother after reading it,” said the future Sir Doyle. “However, without a knowledge of local conditions I couldn’t attempt to set up an opinion against those of your police officers. I can quite understand how, in the first instance, the public may have thought that the family knew something more of the affair than they stated, but I concluded that the father’s story was so unusual that it must be true. As to the present prisoner, Clara Ford, I cannot offer an opinion; I never met with such a case as hers. The system of closeting a prisoner with an officer and cross-questioning her for hours, savors more of French than English methods of justice.”

* * *

Arraigned for trial at the spring assizes, Clara Ford appeared before Chancellor (later Sir) John Boyd on April 30, 1895. The prosecution was headed by B.B. (Britton Bath) Osler, who at 63 was widely regarded as the foremost criminal lawyer in Canada, having served as the prosecuting counsel in the trials at Regina arising out of the Riel Rebellion of 1885. Assisting Osler was Crown Attorney Hartley Dewart, who would later become leader of the Liberal party of Ontario. Defending Clara Ford were her accomplished defense attorney, E.F.B. (Ebenezer Forsyth Blackie) Johnston, a crackerjack criminal lawyer as well as a leading authority on the fine arts; and his assistant, attorney W.G. Murdoch.

For four days the twelve-man jury heard the evidence. (Women had no legal standing as “persons” and so were exempted from jury duty in those days.) There was considerable speculation as to motive, and the Crown alleged that Westwood and Ford had been intimate. It was, in the words of the World’s anonymous scribe, “the old story of love and passion, condemned by the law of God and man.” The prosecution produced a witness, Libby Black, who claimed to have seen them together. The accused smiled incredulously as this witness gave her testimony. Almost completely lacking in credibility, Libby Black proved a disaster for Osler and Dewart, who must have cringed when she divulged that she was presently in legal custody for public drunkenness. As well, her description of Westwood involved a heavy moustache and other characteristics which he did not possess.

Forensic experts pointed out that the revolver could have been the murder weapon, but that similar weapons could also have made identical striations. Flora McKay, who could not hide her deep affection for the prisoner, told of their unsuccessful tryst outside the Toronto Opera House that fateful Saturday evening. Mrs. Crozier, Mrs. Phyle, friends of Westwood, and innumerable others took the stand, each in turn. Murdoch questioned Mrs. Phyle so aggressively that she commenced weeping. The Judge told Murdoch: “She don’t understand your question and it’s a question no mortal could answer if understood.” Thus ended the cross-examination of Mrs. Phyle.

After the Crown had presented its case, Mr. Johnston argued that the confession of Clara Ford was inadmissable, since it was made in the “sweat-box” under conditions of extreme duress. He recounted that she had been held without advice and plied with questions for many hours. “The detectives you have seen here are vultures in human form,” he said. “They subjected this woman to brutal and inhuman treatment from four in the afternoon to eleven-thirty at night in order to force her to confess. I am ashamed to belong to the same race of human beings. I ask you to free her as a protest against this autocratic and czarlike attitude assumed by the police.”

Unfortunately, Osler wasn’t in court to hear this or any other part of the formal defense; his wife had died the previous night. His absence would lend a crushing blow to the prosecution. His Lordship declined to grant a postponement, however, saying such would be unjust to the jury. As for Clara Ford’s confession, he allowed it. Various other procedural matters and witnesses were dispensed with. Finally, Clara was called forward. She took the stand and despite invitations to sit down, remained standing as she gave testimony for more than three hours. She admitted giving her story to Sgt. Reburn, but swore it was a fabrication. She told of how the detectives had picked her up at Barnett’s shop, took her back to her room, asked about her men’s clothing and revolver, which she freely admitted to possessing. Her story was that she had purchased the gun at a second-hand store on York-street three years earlier, and that it had not left her trunk for more than a year, and then only so she could shoot at some ducks on the lake. They had asked if she possessed a false moustache, and she had looked them straight in the eye and said no. She complained that she had been grilled very roughly, and that no one had ever cautioned that her own words could be used against her. “The prisoner’s statement that she had knocked around the world earning her own living for twenty odd years explained the coolness with which she faced the crowded court room. It may also have accounted for the utter indifference she manifested to the fact that she was on trial for her life. The laughing way in which she alluded to the frightened condition of witnesses who were brought to confront her showed that she relished the notoriety she was receiving. She had admired and envied weekly the heroines in the plays at the theatres, and she enjoyed the fact that she was at length the central figure in a drama, even though it were being played on life’s stage and the finale was fraught with such momentous results to her.”

Summing up, Johnston said: “In going into the witness-box my client has exhibited the charm and confidence of innocence, and you have witnessed one of the boldest, noblest, most heroic acts ever seen in a court of law. I know that you will do justice to her and acquit her of the charge so fiercely pressed against her by Sergeant Reburn.”

It took the jury only forty-eight minutes to reach unanimity in the verdict that would soon be proclaimed on the front page of every newspaper in town: Clara Ford Acquitted. This was a case “full of strangeness,” the Judge had said in discharging the prisoner, adding: “Be kind to Flora McKay. She showed her affection for you when the evidence against you was strong, and she attempted to shield you from suspicion.”

Upon announcement of the verdict, the court room broke into a joyous tumult. Crowds of sympathetic witnesses and spectators swarmed the ex-prisoner, kissing her and shaking her hand. More throngs of cheering well-wishers greeted her on the street, and many followed, walking arm-in-arm, as she rode triumphantly along Adelaide-street to York-street. “The girl was followed by an immense mob, which swelled in numbers every moment,” reported the World. “When Mrs. Dorsay’s was reached the throng filled the roadway from curb to curb.” Inside, the city’s newest cause celebre spoke to the cheering mob, which — incredibly — included the foreman and several members of the jury: “I thank you for the way you stood by me. This does the boys of Toronto credit. I thank you all.”

Wrote Hector Charlesworth in his 1925 memoirs: “I saw her proceed in a carriage through the streets followed by a cheering throng, and in gratitude she asked the jurors to supper at the negro restaurant where she had boarded. The invitation was accepted; and the presiding judge, Chancellor Sir John Boyd, told me subsequently that it was the most disgusting example of the weakness of the jury system he recalled in a long experience.

“Once free she was unabashed in admission of her guilt. Her first step was to arrange for her appearance in a dime museum [Eden Musee] in the clothes she had worn when she killed young Westwood. This was too much for her counsel, Mr. Johnston. He sent for her and told her that but for him she would be facing the gallows; and that if there were any remnants of decency left in her she would immediately leave Canada. She took his advice and joined ‘Sam T. Jack’s Creoles,’ a coloured burlesque show, and was advertised in the Western States as a damsel who had killed a man in pursuance of ‘The unwritten law.'”

That week, the papers reported the opening of another sensational murder case, involving the twin Hyams brothers, who were being tried for committing murder and insurance fraud; the prosecution’s main witness was a suspicious and fearful wife. The public quickly seemed to forget the matter that had so inflamed its curiosity on and off for months. As the World noted, “The crime, which has created such sidespread interest, will be forgotten in the lapse of years, but it will be bared again by the recording angel, and justice such as only God can give will be meted out to the gulty and to the innocent.”

In 1945, a full half-century after Clara Ford abandoned the city of her notoriety, author Edwin C. Guillet published The Shooting of Frank Westwood, a thin, typewritten legal study of the evidence in The Queen versus Clara Ford. “It has been suggested with considerable plausibility that Clara was infatuated with Frank and that he spurned her, and possibly cast reflections upon her Negro blood,” he wrote in a concluding paragraph. “The Westwoods were wealthy, Clara Ford poor and hard-working, and if anyone thought an attractive mulatto was fair game for a good-looking, better-class man-about-town, the jury begged to differ. The fact that she habitually carried a revolver suggests that working and living in a somewhat disreputable district made that course of action necessary to keep the wolves of the day at a respectable distance. Clara Ford had not had much of our boasted equality of opportunity, and perhaps both her crime and her acquittal are not difficult to condone. If she killed Frank Westwood no little aggravation must have provided the motive; and the case would consequently be more one of manslaughter than of murder. It can therefore be said, at least, that to have hanged Clara Ford would have been a greater miscarriage of justice than her acquittal; and it certainly seems that, however guilty she was, her confession was extorted from her by high-pressure methods.”

* * *

Morbidly curious readers wishing more knowledge of this century-old affair may wish to consult a play by T. Gauntley, published in a very limited edition by the Swansea Press of Toronto only four years ago. Its full title: “The Seance of Lakeside Hall, Otherwise Known as The Great Parkdale Mystery, wherein the shocking murder of young Frank Westwood and singular arrest of Clara Ford entangle the then-visiting Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle, celebrated author of the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.” A single copy of the manuscript, set in an ordinary typewriter font, resides in the Metropolitan Toronto Central Reference Library, Yonge-street — aptly enough, in the Arthur Conan Doyle Room. ♦

© 1994