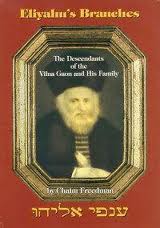

Israeli genealogist Chaim Freedman gained much expertise in rabbinic genealogy by compiling the family tree of the legendary Vilna Gaon, which was published as Eliyahu’s Branches in 1997 on the 200th anniversary of the great sage’s death.

Israeli genealogist Chaim Freedman gained much expertise in rabbinic genealogy by compiling the family tree of the legendary Vilna Gaon, which was published as Eliyahu’s Branches in 1997 on the 200th anniversary of the great sage’s death.

In his new treatise, Beit Rabbanan: Sources of Rabbinical Genealogy, he attempts to impart some of his knowledge to the beginner who may or may not have an adequate command of Hebrew; advising early on, however, that some knowledge of the language of rabbinical discourse is essential.

Freedman discusses many issues and difficulties pertaining to rabbinical genealogy, and examines the central question of the relevance and admissibility of oral tradition as a genealogical source. The discussion, which seems to meld genealogy with Talmudics, is illuminating.

Freedman found many families that claimed a relationship to the Vilna Gaon based on oral traditions, and categorized them into three groups.

First were the claims that could be easily corroborated by reliable sources and records. These, naturally, proved the least problematic.

Second were the claims that stood up to critical scrutiny and could ultimately be judged as being “highly likely to be valid, beyond any reasonable doubt.”

Third were the claims for which insufficient evidence could be found. Freedman further subdivided this category into cases that seemed dubious enough to exclude, and cases that seemed promising enough to warrant collecting all available genealogical data should an authenticating link surface one day.

As Freedman notes, some oral traditions are patently false. In one instance, some basic genealogical research demonstrated that a person who was supposedly an only child actually had 20 siblings!

Still, he insists that a “legendary kernel of truth” underlies every oral tradition, but that it often gets mixed up in the transmission from generation to generation: It’s up to the wise genealogist to find it.

Genealogists are used to working in empirical proofs, not probabilities, so it may seem a bit disconcerting to some readers that Freedman seems to advocate educated guesswork in cases where extensive research has failed to turn up documented sources.

Freedman’s discussion trails off without really explicitly stating that the use of a “quantum leap” in genealogy, based on speculation, is perfectly acceptable, provided it’s carefully identified as such. It would be totally wrong, however, to mislead anyone into believing that solid documentation underlies the genealogist’s “best guess” when there’s really no documentation at hand.

I find it fascinating that Freedman cites principles of Jewish law to support the use of oral tradition as genealogical evidence.

He notes, for example, that the late Rabbi Shmuel Gorr used to expound the Talmudic principle of “ain lo raiti raeh” — that simply because you have not seen it (a proof) does not mean it does not exist.

The intersection of genealogy and the Talmud seems a very fruitful area for discussion. I wish Freedman had developed these ideas further.

The section on Sources of Rabbinical Genealogy offers a thorough bibliography of titles, many from the 19th century. The book also discusses prenumeranten, donor lists, Hebrew and Yiddish newspaper lists and many other sources.

Beit Rabbanan is essentially a beginner’s guide. The author’s great enthusiasm and reverence for the subject always shines through, even if the book seems idiosyncratic and disorganized in places.

On a personal note, I discovered a special reason for liking this book. In its last few pages, the author discusses a rabbinical family, the Berliners of Piotrkow, Poland, that are linked by at least two marriages to the Glicensteins, a family that I have been researching for many years.

Large format, soft-cover, 70 pages. Privately printed in Petach Tikvah, Israel, 2001. ♦

© 2002