The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints — better known as the Mormon Church — made internet history recently with the opening of its genealogy website.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints — better known as the Mormon Church — made internet history recently with the opening of its genealogy website.

Planners were cautiously optimistic that the site might receive as many as one million hits per day. But when they were beta-testing the site, its URL address leaked out, and it soon began to receive some 5 million hits per day.

Like the Essenes who reportedly hid the Dead Sea Scrolls in a cave in the Judean hills almost 2,000 years ago, a latter-day Christian sect has dug a vault in a Utah mountain for storing microfilm copies of millions of documents it considers essential to humanity.

To date, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), commonly known as the Mormon Church, has amassed nearly two million rolls of microfilmed birth, marriage, death, census, military and other genealogical records that pertain to most major nations, ethnic groups and religions on earth.

Church officials estimate they possess information on some two billion human beings who died within the last 400 years. With about 200 camera operators presently operating in some 40 countries, the collection grows by thousands of rolls of microfilm every month.

The Church has gone to these extraordinary lengths because of its fundamental belief in the permanence of family ties. Adherents are required to chart at least four generations of their family trees, then perform a religious rite called “sealing” so that spouses, children and ancestors will be joined together in the hereafter. Spokesperson Thomas E. Daniels agrees that the process is essential a form of posthumous baptism. Non-Mormons are permitted to use the library and encouraged to deposit their genealogies, which may provide essential connections for Mormon researchers.

The Church has gone to these extraordinary lengths because of its fundamental belief in the permanence of family ties. Adherents are required to chart at least four generations of their family trees, then perform a religious rite called “sealing” so that spouses, children and ancestors will be joined together in the hereafter. Spokesperson Thomas E. Daniels agrees that the process is essential a form of posthumous baptism. Non-Mormons are permitted to use the library and encouraged to deposit their genealogies, which may provide essential connections for Mormon researchers.

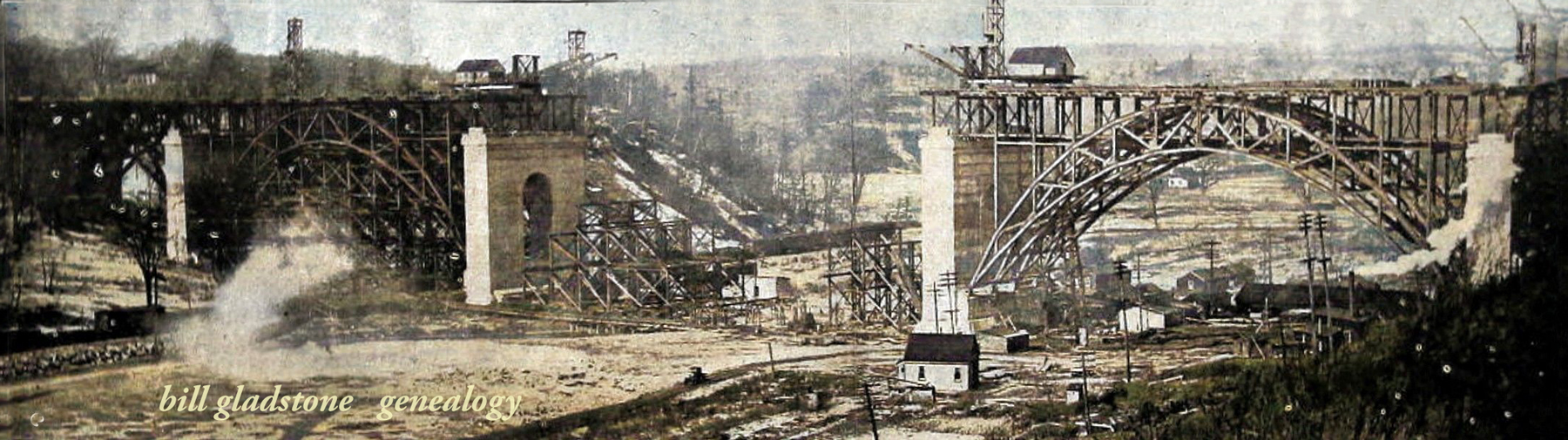

Master negatives of the microfilms are stored under optimum conditions of humidity, temperature and light in the Granite Mountain Records Vault in a mountain outside Salt Lake City. Built in the 1960s at the height of the Cold War, the vault is supposedly impervious to flood, fire, tornado, earthquake, even nuclear war.

Copies of the microfilms are freely available at the LDS Family History Library in downtown Salt Lake City. The library, which commemorates its centenary in 1994, also possesses a vast book and microfiche collection as well as the International Genealogical Index (IGI), a computer listing of some 200 million names from multiple sources, including Mormon and other donated genealogies. Such resources have won the library a well-deserved reputation as one of the foremost genealogical research facilities anywhere.

About the only book the Church refuses to open is the one containing its own balance sheet. “I haven’t any idea of the budget and even if I did know, the church doesn’t discuss income or outgo,” says Daniels. “It’s all funded from tithes — from our members’ donations.”

Because a preponderance of Mormons are North Americans formerly of British stock, the library is strong on Canadian, American and British records. But it also holds a vast array of European, South American, African, Australian and Asian records, including records from Third World countries like China and India. The collection reflects the diverse roots of Church adherents, many of whom converted from other denominations and faiths.

Since the collapse of the Berlin wall and communism, LDS camera operators have moved into formerly restricted communist-bloc regimes like the former East Germany, Belarus, Slovakia, Estonia and Armenia. Contracts to film are currently being negotiated in Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Romania and other places. “Our emphasis (in Europe) has been diverted from the west to the east,” says LDS Slovak authority Daniel Schlyter. “We have only so many cameras and we want to take advantage of the window of opportunity that has opened in the east.”

Since the collapse of the Berlin wall and communism, LDS camera operators have moved into formerly restricted communist-bloc regimes like the former East Germany, Belarus, Slovakia, Estonia and Armenia. Contracts to film are currently being negotiated in Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Romania and other places. “Our emphasis (in Europe) has been diverted from the west to the east,” says LDS Slovak authority Daniel Schlyter. “We have only so many cameras and we want to take advantage of the window of opportunity that has opened in the east.”

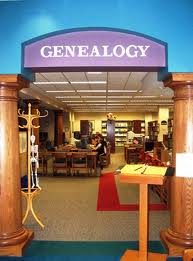

It’s not necessary to travel to Utah to use the library. Materials are easily available through thousands of branches in the United States, Canada and Europe. (Metro Toronto has two, in Etobicoke and Scarborough.) Patrons of most branches may consult either the microfiche or CD-ROM version of the library catalogue, then pay a modest charge (usually $4 to $6) to order a specific microfilm, which may take several weeks to arrive.

Despite the convenience of doing research remotely, many serious genealogists eventually make the pilgrimage to Salt Lake, where material is quickly accessible on open shelves. The Utah facility is one of the best spots anywhere for “one-stop shopping,” says Gary Mokotoff, the New Jersey-based president of the Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies. “I’ve been telling people for years: if you need death records from Chicago, go to Chicago; if you need United States passenger lists, go to the National Archives in Washington; and if you need marriage records from New York, go to New York. Or you could just go to 35 North West Temple Street in Salt Lake City.”

The Utah capital’s importance as a genealogical centre is evident even at the airport, where strangers strike up conversation about the British census of 1891 at the baggage carousel. Genealogical talk is overheard everywhere, in restaurants, on sidewalks, even in the private clubs where alcoholic drinks may be purchased without accompanying meals.

The library occupies a prime site in town directly across from Temple Square, a 15-acre walled enclave containing the Temple, Tabernacle and other historic Mormon buildings. Every day except Sunday, some 3,000 genealogical pilgrims enter its doors, which are generally open from 7:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. The library receives about 850,000 visitors each year and the number is growing; the boom sparked in the mid-1970s by the print and TV-miniseries versions of Alex Haley’s Roots shows no signs of abating, church officials say. “It’s a busy place,” Daniels comments. “People come from every state in the union and many countries all over the world.”

Research areas are divided geographically onto four floors, with banks of microfilm cabinets and readers nearly everywhere. The library has also kept up with the computer age. Computers and CD-ROM equipment are common in both the main library and its recent adjunct, the elegant Joseph Smith Memorial Building, where patrons search the IGI for connections to their own lineages. Computers have shortened many searches and allowed for more complex types of research, but have not reduced the substantial time commitment necessary to do the job properly.

“I’ve seen people getting off a Gray Coach bus on a bathroom break and run into the library, expecting to find their great-grandparents in five minutes,” says Eileen Polakoff, a Manhattan-based professional genealogist. “There’s this misconception that computers have taken all the work out of it. The truth is, you can’t just hit a button and expect to find your grandfather’s death certificate. Even very educated and intelligent people in New York are amazed at this.”

Another misconception is that genealogy, like most avocations, possesses a beginning, middle and an end. Jim Warren puts it succinctly: “Genealogy expands to fill the lifetime available,” he says. “Most of the time it stops when people decide they have to stop to put a particular line in print, or they’re never going to do it. But from a literal standpoint it never ends. You never come close to depleting the number of records you could search.” ♦

© 1999