It has been 50 years since Winnipeg-born writer Adele Wiseman scored the highly impressive professional coup of winning the Governor General’s literary award for her first novel, The Sacrifice.

It has been 50 years since Winnipeg-born writer Adele Wiseman scored the highly impressive professional coup of winning the Governor General’s literary award for her first novel, The Sacrifice.

But Wiseman, who was 28 in 1956 and widely considered to be at the start of a very promising career as a novelist, disappointed the expectations of editors, critics and a large international pool of readers who would have welcomed a second novel from her within a few years.

No such book was forthcoming. Instead, she focused her creative energies on a play, The Lovebound, a four-hour, unproduceable tragic-comedy about the world’s failure to rescue European Jewry from what would become the Holocaust. Readers had to wait another 18 years for another Wiseman novel — Crackpot — which received a far less exuberant critical reception when it appeared in 1974.

Wiseman’s poor career choice is the equivalent of an award-winning sprinter deciding to swim the English Channel as an encore. Writing in Saturday Night magazine, critic Adele Freedman described the author’s decision to attempt a play as “an act of daring that eventually proved a mistake . . . . Against the advice of her supporters at Macmillan and Viking, she asserted her determination and willfulness like the heroine of a Greek tragedy testing the elements.”

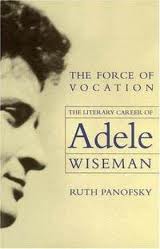

Sadly, the literary artist’s star was never to regain its lustre; she died in 1992. “The course of Wiseman’s career can be read as the progressive loss of readership and literary recognition, with little economic gain over a lifetime,” writes Ruth Panofsky in The Force of Vocation: The Literary Career of Adele Wiseman (University of Manitoba Press), a well-written, newly-published study of Wiseman’s career path and the forces that shaped it.

Rather than attempt a personal biography, Panofsky focuses on Wiseman’s relations with editors, publishers, fellow writers and others within the professional sphere. Novelist Margaret Laurence, a lifelong friend with whom Wiseman maintained a decades-long correspondence, is portrayed as the strongest of the various supporters and mentors who stood by her through her unrelenting lean period.

Wiseman didn’t give a hoot about prevailing market conditions in the book trade or what a project might bring her financially. Convinced of her own vision and the importance of remaining true to her art, she initiated literary projects through an artistic need to grapple with major issues of morality, truth and humanity. She worked in whatever genre she felt was most suited to a given project and, despite the pleas of editors, had no interest in sticking with a more popular form that had already won her a readership. Her eye was always on higher things.

Wiseman didn’t give a hoot about prevailing market conditions in the book trade or what a project might bring her financially. Convinced of her own vision and the importance of remaining true to her art, she initiated literary projects through an artistic need to grapple with major issues of morality, truth and humanity. She worked in whatever genre she felt was most suited to a given project and, despite the pleas of editors, had no interest in sticking with a more popular form that had already won her a readership. Her eye was always on higher things.

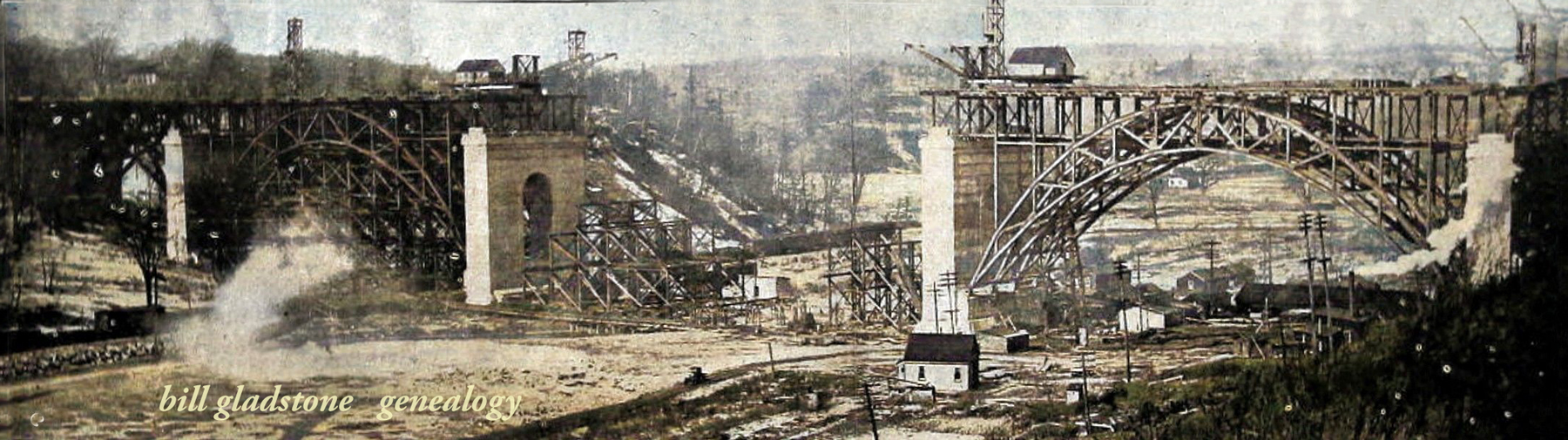

During her early years in Winnipeg, as well as during her literary apprenticeship in London (where she worked for the Stepney Jewish Girls Club) and her later years in New York, Montreal, Toronto and Banff, Wiseman always saw herself as a writer of integrity and vision who stuck by her own muse. “I’m afraid I’m incurably pig headed about my own literary judgement,” she once wrote defiantly after MacMillan of Canada rejected Crackpot for publication; she also bridled upon hearing her characters described as “grotesque.”

Panofsky relates many more psychologically telling professional incidents. Several years after Crackpot’s eventual publication by McClelland and Stewart, for example, Wiseman became livid at hearing that the novel was being remaindered at W.H. Smith bookstores for $1.99. During an angry exchange of letters with publisher Jack McClelland, he scolded her that she seemed to know nothing about the realities of book publishing and “had come to believe that the world owes you some very extraordinary considerations as an artist.” Wiseman shot back that artists were indeed entitled to “extraordinary consideration.” Truth seems to reside on both sides of their angry debate, which permanently damaged their relationship.

The Force of Vocation serves to remind us how good The Sacrifice is, and why it’s earned a coveted spot in the canon of Canadian post-war lit. An English teacher at Ryerson, Panofsky posits that the book’s success was all the more remarkable because its author was a woman in a male-dominated publishing world: too bad we know so little about The Sacrifice’s lonely process of creation. Panofsky also reminds us that many have come to regard Crackpot as an unsung Canadian classic. That was certainly my impression when I read it some years ago and marveled at its solid construction and rare artistry.

The Force of Vocation serves to remind us how good The Sacrifice is, and why it’s earned a coveted spot in the canon of Canadian post-war lit. An English teacher at Ryerson, Panofsky posits that the book’s success was all the more remarkable because its author was a woman in a male-dominated publishing world: too bad we know so little about The Sacrifice’s lonely process of creation. Panofsky also reminds us that many have come to regard Crackpot as an unsung Canadian classic. That was certainly my impression when I read it some years ago and marveled at its solid construction and rare artistry.

As Canada’s foremost Wiseman scholar, Panofsky conveys an encyclopedic knowledge of her subject; her scholarship is outstanding. She deserves credit for producing this timely study of a writer whose works (including Old Woman at Play, about her mother) are still deserving of a wide readership, especially within the Jewish community. ♦

© 2006