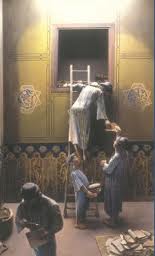

A windowless, doorless chamber, set high up into the wall of an antiquated synagogue and accessible only by ladder, is not normally the sort of place to which a traveller dreams of arriving. However, it was precisely such a room that Solomon Schechter, a Cambridge professor of Talmudic literature, was determined to reach when he left London for Cairo in 1897.

As Schechter knew, the chamber, known as the Cairo Genizah, held a trove of forgotten Judaic manuscripts and published works that had been gathering dust for nearly a millennium. Since Jewish tradition forbids the destruction of items that might carry a sacred name of God, the items had been put into the genizah and abandoned, preserved down the centuries by the same hot dry climate that had preserved the pyramids.

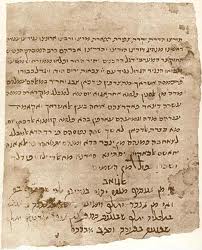

Some fragments had evidently been smuggling out, however, and were being sold; even the British Museum had picked up some pieces. In 1896, two learned Scottish ladies brought Schechter a bundle of weathered parchments they had acquired from an antiquities dealer in Palestine. Poring over one leaf, Schechter excitedly recognized it as part of the original Hebrew text of Ben Sira, also called Ecclesiasticus, an apocryphal Biblical work that for the previous thousand years had been known to scholars only in Greek translation. Within months, he published an annotated version of the Hebrew Ecclesiasticus, causing a sensation. Soon after, he set out to the Ben Ezra Synagogue in the Cairo neighborhood of Fostat, before any more of the genizah’s priceless treasures could be spirited onto the black market and perhaps lost to scholars forever.

In Fostat, Schechter found an embarrassment of riches. After only a cursory inspection, he could concur with previous Jewish travellers who had reported that the storeroom held a vast universe of literary treasures. He estimated that the genizah contained one hundred thousand manuscript and published pages; eventually the estimate would have to be doubled. Presenting several impressive letters of reference, he finagled the permission of the synagogue officers to take whatever he could — but now he wondered, how could he possibly take everything? By necessity, he decided to limit himself to only the handwritten manuscripts, which were generally older than the published works and far more likely to be unique.

In Fostat, Schechter found an embarrassment of riches. After only a cursory inspection, he could concur with previous Jewish travellers who had reported that the storeroom held a vast universe of literary treasures. He estimated that the genizah contained one hundred thousand manuscript and published pages; eventually the estimate would have to be doubled. Presenting several impressive letters of reference, he finagled the permission of the synagogue officers to take whatever he could — but now he wondered, how could he possibly take everything? By necessity, he decided to limit himself to only the handwritten manuscripts, which were generally older than the published works and far more likely to be unique.

“Looking over this enormous mass of fragments about me, in the sifting and examination of which I am now occupied, I cannot overcome a sad feeling that I shall hardly be worthy to see the results which the Genizah would add to our knowledge of Jews and Judaism,” he penned in one of his frequent letters to his wife and colleagues in England. “This work is not for one man and not for one generation. It will occupy many a specialist, and much longer than a lifetime. However, to use an old adage, ‘It is not thy duty to complete the work, but neither art thou free to desist from it.'”

For several weeks Schechter painstakingly sorted manuscripts, his face covered with a gauze mask. Still, the dust “nearly suffocated and blinded me,” he wrote, adding that he had been obliged to seek medical treatment. According to his biographer, Norman Bentwich, his time in the genizah “impaired his health to such an extent that he began to pass almost from the appearance of a young man to a man of considerable age.”

Like his astonishing literary harvest, his disdain for his appalling working conditions grew daily. “I am just back from the Genizah and brought two big sacks with fragments,” he wrote one day. “I must have a bath at once. You have no idea of the dirt.”

Another major source of annoyance for Schechter were the many workers who demanded baksheesh, which he felt compelled to pay in order to safeguard the growing number of sacks of manuscripts he was preparing for export. Upon collecting thirty sacks, he felt an urgency to remove them quickly from Egypt because he felt the “evil eye” upon him. He had by then spent a small fortune in baksheesh, retrieving fragments that had fallen into unscrupulous hands.

Before returning home, he went to Palestine to visit his twin brother, an early settler in the village of Zichron Jacob. From there he joined a ship that also carried Professor Flinders Petries, the accomplished Egyptologist. Somewhat alarmingly, the ship hit a rocky shoal off the coast of France and the hull was pierced. The damage was repairable, though, and in due course all aboard — passengers, crew and cargo — reached London in safety.

* * *

Born in a Romanian village, Solomon Schechter spent the first 30 years of his life in Eastern Europe, devoted to the study of Torah and Biblical literature. Soon after his arrival in London in 1882, he joined a circle of Jewish scholars called The Wanderers, whose members included Asher Myers, editor of the Jewish Chronicle, and novelist Israel Zangwill, the Charles Dickens of Anglo-Jewish letters. It is said that Schechter burst upon the group like “a blazing comet,” soon becoming its dominating spirit and wit. Bentwich compares him to Dr. Samuel Johnson at the Literary Club.

In London, the yeshiva-trained scholar was shocked and disheartened to see that the emancipated and highly assimilated Jews of England had lost the Old-World reverence for the study of sacred literature. “As in Germany with the Bible, so here the holy literature of Judaism is tended only by the Christians,” he lamented. “That is the Galuth Ha Shechinah, the exile of the Holy Spirit. There is no spiritual life here, and I feel myself dead. The manuscripts in the British Museum are my only consolation.”

The Wanderers never recovered from Schechter’s departure to Cambridge in 1890, a move that expanded his academic possibilities as much as it limited his spiritual ones. At Cambridge, he was (and would remain for his 12 years there) the only Jewish member on faculty. His determined goal was to found a school of Jewish learning at the august institution; it was never realized, a failure that increased his bitter conviction that Jewish learning was in exile in England.

But he could still apply his famous wit in defense of Jewish scholarship. Once, a professor asked him why it was that Hebrew scholars did not know Hebrew grammar. He replied: “You Christians know Hebrew grammar. We know Hebrew. I think that we need not be dissatisfied with the division.”

Cambridge enriched Schechter with the friendship of Sir James Frazier, author of The Golden Bough, the classic scholarly work of comparative religion. The two would walk together several afternoons each week, and often continue their lofty conversations in the privacy of their studies.

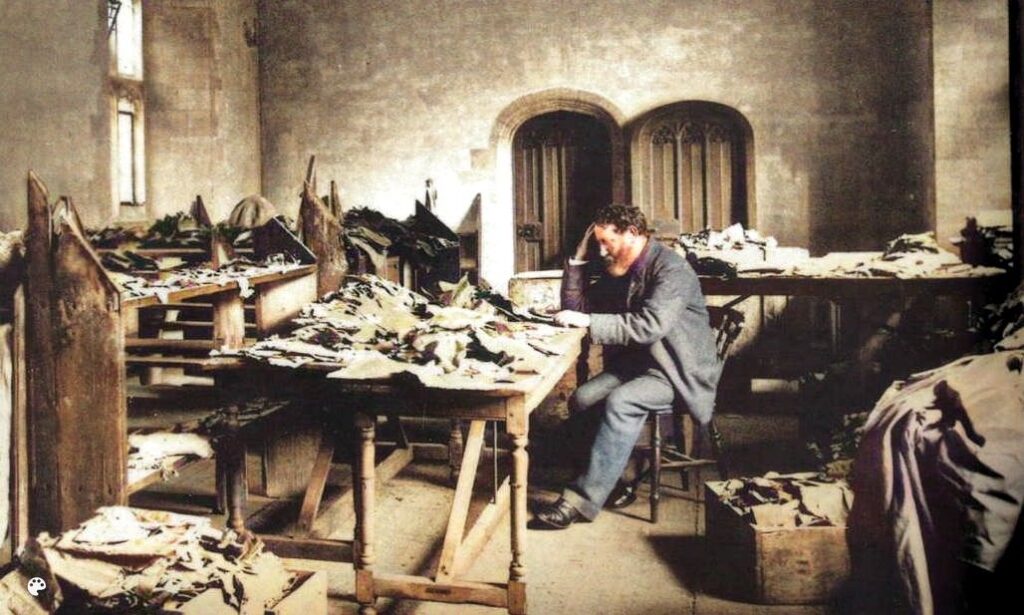

Upon his return from Cairo, Schechter dedicated himself to the monumental task of classifying the hundred thousand genizah fragments he had recovered. In a large room he set up a series of ordinary cardboard boxes, labeled Bible, Talmud, History, Literature, Philosophy, Rabbinics, Theology, and so on. He would take a piece of paper or parchment from the mass, examine it with his magnifying glass, then place it in the proper box.

Upon his return from Cairo, Schechter dedicated himself to the monumental task of classifying the hundred thousand genizah fragments he had recovered. In a large room he set up a series of ordinary cardboard boxes, labeled Bible, Talmud, History, Literature, Philosophy, Rabbinics, Theology, and so on. He would take a piece of paper or parchment from the mass, examine it with his magnifying glass, then place it in the proper box.

In “A Hoard of Hebrew Manuscripts”, a brief and insufficient memoir of his Cairo adventure, he took pains to correct a common misperception. “I should like at once to correct a mistake with which I often meet in books and articles, in which I am described as the discoverer of the Genizah. This is not correct. The Genizah practically discovered itself.” However, it was Schechter who saved its contents for scholarship.

In essence, Schechter’s “hoard of Hebrew manuscripts” were the Dead Sea Scrolls of his day, and they yielded many sensational discoveries beyond the Hebrew Ben Sira. Thousands of fragments were eventually assembled into dozens of complete Bibles in a multitude of languages, many dating from the 10th century CE. Many original pages of Talmudic commentaries by Maimonides (1135-1204), Alfasi (1013 1103) and other renowned Jewish philosophers were retrieved from oblivion. In particular, the genizah richly illuminated the period of the Geonim, the rabbis of the Babylonian academies (7th to 11th centuries), and offered many documents and works of and relating to Saadia (882 942), the most famous Geon. It also yielded an early manuscript of Sefer ha-Kuzari, a 12th-century Hebrew work that told how the Chazars, a pagan people of south Russia, had converted to Judaism in the 8th century CE.

After salvaging this immense wealth of manuscripts, Schechter did not rest on his laurels. Eventually he came to the United States, where he became a chief architect of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, the major institution of Conservative Judaism.

Just as Schechter lamented the lack of Jewish learning among the Jewish masses, so Bentwich laments how quickly his formidable legend has dissipated. “If ever there was a Jewish sage who should have had a Boswell to record his daily sayings, it was Schechter,” he writes. “The essence and genius of the man were shown as much by the table talk and the explosive conversation as by the written word or the scholarly lecture….

“A child of the ghetto, he was also a prophet of Israel. His life, divided between several countries, is an epitome of the development of the Jew in the modern world; and there was no man in his Jewish generation who made so deep an impression upon the thought of his people.”

The Israel Museum in Jerusalem paid a fitting tribute to Schechter two years ago when it hosted a major conference on the Dead Sea Scrolls and focused a significant part of the proceedings on the Cairo Genizah 100 years after Schechter’s important voyage of discovery. Anyone familiar with that accomplishment should not have been surprised. ♦

See also: Obit: Solomon Schechter, foremost Jewish scholar (1915)

Comments:

Dear Bill,

Thank you very much for your fascinating and well-written blog post about the Cairo Genizah. I have a special interest in the topic, as I recently published a book on the subject – Sacred Treasure: The Cairo Genizah. I’m delighted that you too have chosen to share this fascinating story. As you know, the Cairo Genizah is arguably the most important discovery of modern Jewish scholarship, but very few people know about it. I hope that your work – as well as my own and that of others – will help raise awareness of this priceless trove of manuscripts.

I took particular note of Schechter’s comment that you quoted in your article, “The Genizah practically discovered itself.” I read Schechter’s account of his visit to the Genizah dozens of times, but I never noticed that insightful comment. If I had, I might have used it as a chapter-title.

In any case, thanks again for the post. I enjoyed reading it very much. — Rabbi Mark Glickman, USA.

© 2011

1 comment for “Solomon Schecter and the Cairo Genizah”