“To be a Jew and a Canadian is to emerge from the ghetto twice.”

“To be a Jew and a Canadian is to emerge from the ghetto twice.”

When Mordecai Richler made that insightful observation in 1971, Canada was still a literary backwater and postwar Canlit was just beginning to explode onto the international scene.

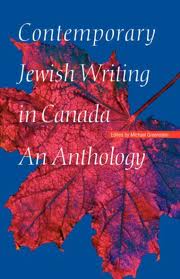

Today, as Michael Greenstein demonstrates in a newly published anthology of Canadian Jewish writing, even our Jewish writers are no longer confined to a parochial ghetto: many, including the late Richler, are fully part of the mainstream culture.

A Toronto-based litterateur who is an adjunct professor of Jewish studies at McGill University, Greenstein is the editor of Contemporary Jewish Writing in Canada: An Anthology, which was recently published in hardcover by the University of Nebraska Press, largely for the U.S. academic market (2004).

Through a lively cross-section of 17 stories and novel excerpts, the anthology reminds us that Jewish Canadians are blessed with a cornucopia of thoughtful, engaging and significant writers, the best of whom breaks all parochial bonds to emerge from the proverbial ghetto.

In a relatively modest number of pages (232), the book manages to highlight our humble Yiddish beginnings, focus on our three main regional centres of Jewish literary production (Montreal, Winnipeg, Toronto), explore our national French-English dichotomy and emphasize the wide diversity of Jewish writers presently writing in Canada.

Countless American undergrads who find this book on their course lists are in for a special treat, especially those who have never encountered the likes of Leonard Cohen or Mordecai Richler. The book opens with excerpts from The Favourite Game, Cohen’s unique 1963 novel, and continues with a segment from Barney’s Version from Richler’s mature period.

It also offers excerpts from the relatively recent mainstream novels Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels, which became a celebrated international bestseller, and Martin Sloane by Michael Redhill, which established its author’s literary reputation in Canada.

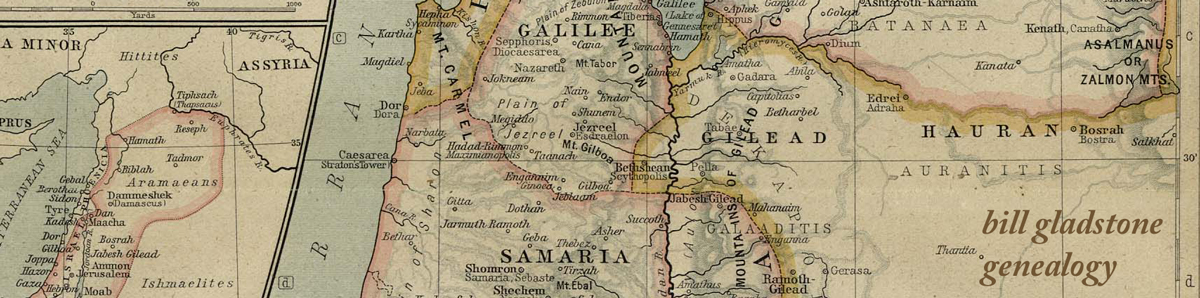

These works, which are partly set in Greece and Ireland respectively, underline a central theme of Greenstein’s symphonic introduction — that Canadian Jewish writers transcend local geography to “find mythologies outside of national boundaries.”

The anthology is spiced with the Yiddish flavouring of “Mrs. Maza’s Salon,” Miriam Waddington’s memoir of her childhood rendezvous with one of Montreal’s leading Yiddish literary lights. Chava Rosenfarb’s story, “A Friday in the Life of Sarah Zonabend,” offers another Yiddish “tam.”

To my knowledge, no previous anthology of this kind has included selections translated from the French, but here we’re offered significant items by Monique Bosco, Naim Kattan and Regine Robin. The book also weighs in with excerpts from two novels by Robert Majzels and an essay by David Solway about Irving Layton, as well as short stories by Robyn Sarah, Judith Kalman, Norman Levine, Matt Cohen, Gabriella Goliger and Aryeh Lev Stollman.

Can such a book get to press without a selection by A. M. Klein? Greenstein thinks so; he more than compensates for the omission by paying due homage to Klein and other excluded worthies in his erudite opening essay.

By putting such a pre-eminent focus on what he calls “the drift of new voices” (even including a section from a novel not yet in print), Greenstein makes an important point. For all the riches of the Canadian-Jewish literary past, this is a genre that seems to be exploding into a new and multifaceted glory just as Canlit began to do a few decades back. ♦

© 2004