What natural feature gives Bon Echo provincial park, in northeastern Ontario, a special reputation among campers? We arrived here late one June afternoon without knowing the answer — but we soon found out.

What natural feature gives Bon Echo provincial park, in northeastern Ontario, a special reputation among campers? We arrived here late one June afternoon without knowing the answer — but we soon found out.

After pitching our tent, we set off on a hike through the tangled forest, threading through stands of birches and pines along a pine-needle path. Eventually, we perceived that something was shining through the trees ahead. It was of great size and luminescence, and seemed to grow brighter as we approached. Then, breaking through the trees, we came to the water’s edge and confronted Bon Echo’s majestic secret.

We stood before a large, peaceful body of water — Lake Mazinaw — and before the enormous rock that juts out of the lake at a sheer angle, towering 100 meters. Because the rock is directly illuminated by the afternoon sun, its pink, gray, ochre and quartz tones seemed to sparkle with light, reflecting as pastels in the shimmering water.

Mazinaw Rock has been called “Canada’s Gibraltar.” It possesses all the mystical power of the desert buttes of the American southwest or Ayers Rock in Australia. In ancient days, aboriginals painted an array of some 135 red-ochre pictographs on the rockface.

Mazinaw Rock has been called “Canada’s Gibraltar.” It possesses all the mystical power of the desert buttes of the American southwest or Ayers Rock in Australia. In ancient days, aboriginals painted an array of some 135 red-ochre pictographs on the rockface.

In awe of the cliff, we followed the coastline, and soon came to a narrow beach, a lagoon, motorboat and ferry docks, and a wide sandy beach. The air was filled with the whoops and cries of swimmers, castle-builders, beachcombers. After a refreshing swim, we took the ferry across the lagoon, and climbed a cast-iron staircase of 180 steps to the lookout on the rock’s summit.

We overlooked a panoramic vista of forest. The sun was nearing the western horizon and the lake reflected the pale gold of the sky. Because of the extreme declension of the sun, each pine ridge was articulated from its neighbour; we could easily adduce where camp was by the blue haze of smoke. According to legend, a horde of Indian gold and silver is hidden atop Mazinaw Rock. Another legend tells of fierce battles fought atop this rock by rival bands of Algonquin and Iroquois, with slaughtered Iroquois combatants falling dramatically to their deaths.

Lake Mazinaw has many bays, inlets, fingers and islands to challenge canoeists. After breakfast on our first morning, we rented a canoe at Bon Echo Villa, a cluster of stores outside the park. Then we paddled across the lake at its widest, scouting in vain for a suitable landing site on the opposite, jagged shore.

Lake Mazinaw has many bays, inlets, fingers and islands to challenge canoeists. After breakfast on our first morning, we rented a canoe at Bon Echo Villa, a cluster of stores outside the park. Then we paddled across the lake at its widest, scouting in vain for a suitable landing site on the opposite, jagged shore.

One spot seemed safe enough, but subsequently proved so slippery and treacherous that we were forced to paddle a hasty retreat. Finally, landing upon a small rock bereft of vegetation, we took a refreshing swim, then rejoined the canoe, covering ourselves with towels like desert wanderers to escape the hot sun.

Recrossing the lake, we returned to the great cliff. Above us, straight from the pages of Twain, groups of rock-climbers were diving into the water from impressive heights. Maneuvering around other canoes, we passed some Indian pictographs, painted only a foot or two above the water-line.

Rounding a vast crag, we came upon an enormous rockface inscribed with a remarkable inscription, dedicated to the American poet, Walt Whitman.

OLD WALT (1819 – 1919)

“My foothold is tenon’d and mortised in granite; I laugh at what you call dissolution, and I know the amplitude of time.”

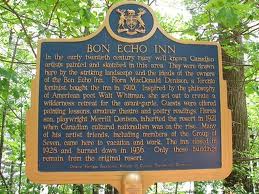

Suffragist and spiritualist Flora MacDonald Denison, who lived in Bon Echo, commissioned this carving on the centenary of the poet’s birth in 1919. Denison ran the Bon Echo Inn, which at its zenith between 1910 and 1920, attracted rich and famous visitors from Canada, the United States and Europe.

Suffragist and spiritualist Flora MacDonald Denison, who lived in Bon Echo, commissioned this carving on the centenary of the poet’s birth in 1919. Denison ran the Bon Echo Inn, which at its zenith between 1910 and 1920, attracted rich and famous visitors from Canada, the United States and Europe.

Relaxing along a small public beach, we noticed dark clouds sailing over the pine ridge and set off in the canoe for the rental establishment, about three miles distant. Over the middle of the lake the clouds had burst, lightning forked and thunder rumbled. We paddled close to land, ready to scramble ashore at a moment’s notice. The air darkened and quivered, but the storm held off until the white dot along the water, a marker of our destination, grew into a full-sized Esso sign.

That night, after the storm had passed, the aurora borealis danced in a sky full of stars, and we went walking with a flashlight. We had not gone too far beyond the campground when we felt the imaginary eyes of wolves and bears upon us, and thought it prudent to return to the safety of our comforting cluster of humanity. ♦

© 2006