Thousands of cases never see cruel light of publicity

All the Officials Seek to Settle People’s Trouble Out of Court If Possible — Sifting Out False from True Evidence a Big Task for the Crown Attorney — Jacob Cohen, J.P. Has Troubles of His Own Settling Those of His Countrymen

From the Toronto Star Weekly, September 17, 1910

“I’m an angel,” she reiterated to Clerk Webb, quite soberly — coldly, for people so often would gainsay her.

“Yes,” he temporized. “I always knew that.” He had never seen the lady before but Clerk Webb is a diplomatic man.

For the woman it was a pleasing surprise to have found one man so sympathetic, one whose keener perception could recognize ethereal merits so readily. That was just the one detail about which so many others had been careless and caused her endless days of mundane worry. This was refreshing. As for the clerk, he has a kindly face and a soothing manner.

“Who says you’re not?” almost wrathfully he was prepared to take up her cudgels of defence. He must think rapidly.

“Everybody, chiefly the landlady,” she confided, warming up to her troubles.

Tactfully he agreed that landladies sometimes are annoying for already he thought he had summed up her ailment. There is one man in the City Hall who for twenty years has listened to all manner of unusual complaints and those twenty years have made the clerk of the Police Court skilled and patient in divers frailties of the public, fantastic though they may be. Some would have diagnosed her case as insanity, but he has specifics of his own to apply. He termed it merely a delusion, he will even tell you that all people have delusions, though most of them are less troublesome. In time he learned that the lady wanted an injunction against the landlady and all the inmates of her boarding house. She had spoken to them many times, still those stupid mortals persisted in passing to her, an angle, food and dishes direct from their fleshy hands, not cleansed with serviettes.

Logic did its work. Argument that it would be far more in keeping with her caste to overlook the ignorance of poor sordid beings was seemingly rewarded, for she thanked him affably, and went her way, and did not return.

That is one of the scenes “behind the curtain” of Police Court circles. Impetuosity, or unreasoning doggedness, or the heat of anger carry them there every day, shamefacedly, many times in the face of publicity, for by then they have cooled. Ten scenes happen behind the doors where one is aired in public.

Colonel Denison’s Repartee

When thirty-four years ago Colonel George Taylor Denison took up the office of Toronto’s Police Magistrate, Toronto had scarcely cast off her swaddling clothes though her magistrate was [not yet] an old colonel but a young man. Then the most her seventy-one thousands of people could do was to keep their vigorous colonel busy at a half-day session, for he brought his military spirit of brisk despatch with him.

When thirty-four years ago Colonel George Taylor Denison took up the office of Toronto’s Police Magistrate, Toronto had scarcely cast off her swaddling clothes though her magistrate was [not yet] an old colonel but a young man. Then the most her seventy-one thousands of people could do was to keep their vigorous colonel busy at a half-day session, for he brought his military spirit of brisk despatch with him.

But alert though he was, it transpired that the refractory element piled up his duties with such startling rapidity that even he declined to keep pace with those who possibly through the get-even principle, have tried to work him into his grave. At any rate, there are now three daily sessions where originally there was one, and there are two magistrates and two J. P.s who dole out sentences or reprimands.

Still, synonymous with the thought of the Police Court, comes to mind the name or figure of Colonel Denison, for that is the one name which thousands have learned through association, and a good many thousands more have seen so many times in print that it’s grafted to their memory, and there are so many bright anecdotes padded with humor connected with his magisterial career, and so many breezy little skits have been written of his quick-fire methods and his repartee where the prisoner invites it, that among a class of visitors it has become the Mecca to be seen.

Daily they come to be amused, they have confessed it. But, doubtless to say, they go away disappointed, or if they do laugh, they laugh but half-heartedly, as aliens, for they see but half the pith, the rest lies in the familiarity which has sprung up between the colonel and some of the habituals through long years of recognition. The only time the real quips exist is where they continue a conversation filled with cross-fire epigrams broken off thirty or sixty days ago only through press of time. The rest are platitudes. Even at these some may laugh, but that is pure brutality, or mockery, deserving the speedy censure they meet.

Only those can engage him, who through the wisdom of long attempts have learned his pet foibles, who can speak intimately, and at times sanely, of Imperial unity, or things across the sea, for he is essentially British, and as such can pause to fence.

As in all thing official the magic vantage-point is the glamor of the inside, the matured childishness which must see the inner working, for court sounds themselves are prosaic, too tragic to one or other of the participants, barring the incorrigible who do not profit by reasoning.

Stopping the Phone Bells

Another woman strolled into the same room some time ago, and opened fire with a prologue. “The Bells! The Bells!” For a moment the clerk fancied an advance theatrical agent. “The ‘phone bells. They’re ringing in my ears! Can’t you stop them?”

“I never did like telephone bells myself,” he readily assented. That’s the secret of his antidote, complacent agreement. What the woman wanted was a summons to take to central to restrain her from using all ‘phone connections to her head.

“Often I hear them,” she persisted, “they start always. In church I hear them. Once in the middle of a sermon they came from the preacher’s pulpit. I just got up and told him to stop them, the bells which were ringing in my ears.”

“Well?” He was curious.

“A man came up the aisle and whispered that outside they couldn’t be heard.”

He argued that it was a matter of will power, that she should say to them, “Stop bells,” and repeat it time and again until they did stop. Strange to say, that woman came back in a week’s time with her wildness all gone and thanked him rationally. She could even laugh at her own hallucination.

Crown Attorney’s Trouble

Other things are a mystery, the modus operandi of the Crown Attorney, who figures first in the bevy of secret guarders, the man who must be on his guard both fore and after, for he finds it as great a labor to fight against false evidence which would convict wrongfully as to keep the criminal from slipping through his fingers on “stalled” evidence.

Other things are a mystery, the modus operandi of the Crown Attorney, who figures first in the bevy of secret guarders, the man who must be on his guard both fore and after, for he finds it as great a labor to fight against false evidence which would convict wrongfully as to keep the criminal from slipping through his fingers on “stalled” evidence.

Trivial matters are tacked to Mr. J. Seymour Corley’s skirts as well. Flat refusals are sometimes necessary for the summons seeker. A short time ago a seedy looking man pressed him keenly, vowing for a fact that the prominent business man who had taken his hat at a restaurant and left in exchange one of the better texture was a deliberate thief. At times some people must be shown the door and be mirrored in their littleness, otherwise irreproachable men would be held up to public scandal on the most flimsy evidence.

A stream of people storm his private office who shun the courtroom adjoining. They are those who fight out in the privacy of the Crown Attorney’s rooms the thousands of cases which never reach the courts. They number as many as the court’s hearing, and there have been sixteen thousand on the court’s docket since the new year. These are cases of which neither the magistrate nor the public hear, and many times not even some of the principals. Charges are laid under misunderstanding, the heat of the moment, the pettiness of spite, of pure perversity, and these it is he constantly fights away. Perhaps he goes into details with a solicitor, he is satisfied no complaint exists, perhaps it is a civil matter, perhaps it’s a case of morals, perhaps it’s a trivial matter for police disciplining.

An excited man came one day. He wanted a prominent hattery store arrested. He had bought a hat and its color caused his companions to jeer, but they refused to refund. Departmental stores had made a practice of refunding, so the hatter must be arrested. Scores of other times he’s an educator, discriminating between personal grudge and criminal offences.

Errs on Leniency Side

The time he saves is a factor. The little whispering conversations he has with the magistrate on the bench mean : perhaps that he has grave doubts of the truth of the Crown’s evidence, and the pitched battles fought out in his own room before the session mean that he and the defending counsel have agreed that the salient feature of a case is one point, and around that they must get the decision. Time is saved from wrangling, and the magistrate is unburdened, and perhaps is the only man who does not know each case in part before the hearing.

Always admitting the possibilities of injustice, watching J. Seymour Corley one would say that if he erred he prefers that it be on the side of leniency. Real criminals will come back anyway, he reasons, and so he takes the ground that he is not counsel first for conviction, but counsel for truth.

Human scenes, the most prolix and intricate of all, are waged in the corridor just outside the court door. There a jovial Hebrew man is to be seen daily, the bulwark which stands between the Crown Attorney and the whole Jewish race. He came with the present Crown Attorney, for that official’s time is precious, and oh! my! the turnings of that race are trivial and complex and multitudinous. He is another of those curtain shifters who keep the trouble-seeking swarm from what they seek.

A Solomon in Wisdom

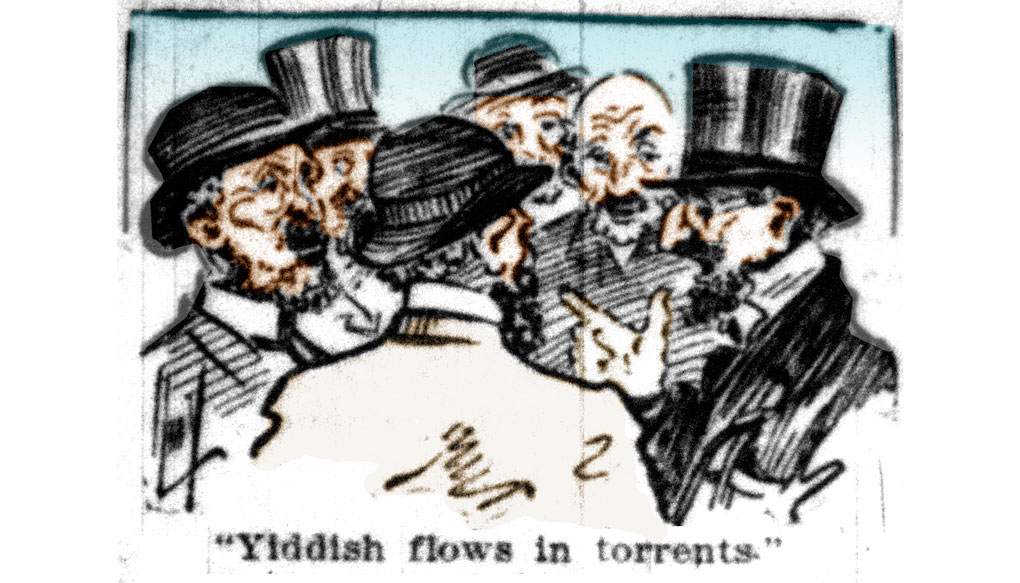

The whole colony know his routine, so they camp upon his trail, and burden his shoulders with their tangles. His daily sessions, unofficial, in the court hallway, occupy the mornings, and his brain is so agile, and his blandishments so soothing, that ten go away smiling where twelve came scowling. Yiddish flows in torrents, and wherever there is a circle of arguing Jewish faces, no one ever needs to ask who holds the oil-keg [i.e., lantern]. Things legal to that race are a mystery, so they rush in blindfolded, and only his weeding out of all but the absolutely criminal stalls off the necessity for an individual foreign court.

The whole colony know his routine, so they camp upon his trail, and burden his shoulders with their tangles. His daily sessions, unofficial, in the court hallway, occupy the mornings, and his brain is so agile, and his blandishments so soothing, that ten go away smiling where twelve came scowling. Yiddish flows in torrents, and wherever there is a circle of arguing Jewish faces, no one ever needs to ask who holds the oil-keg [i.e., lantern]. Things legal to that race are a mystery, so they rush in blindfolded, and only his weeding out of all but the absolutely criminal stalls off the necessity for an individual foreign court.

He will sigh over his “poor silly people,” and shake his head, and bemoan the toil they make him, but there is satisfaction in his manner. And when you twit him with the taunt that he wouldn’t be happy without it, he will only smile inwardly, shake his head again, pat you on the shoulder, and say gently, “Never mind, my boy, it’s all right. You know what I mean? It’s all right.”

That is Jacob Cohen, J. P.

But his wisdom is Solomonic. As sole arbiter of the Hebrew race, guileless externally, he must needs be a wily man. So there are manipulations behind the scenes which save his people from the courts. Ruse or subterfuge, it is all one, the aim is to keep them from themselves. On either arm they nag him . . . . [“Best to let] him go,” he advises the magistrate scores of times, for he tries to avoid technical convictions.

Knows Thousands of Secrets

If Chief Inspector Archibald could tell the secrets he knows of Toronto homes, he would startle the city and set countless tongues wagging to weariness from gossip. For years, Inspector of the city’s morals, ungenteel secrets of people’s lives have flown into his ears and remained locked here. Scathing things he could say of the foolish and injured who have confided in him, the sauce of gossip-mongers till they became drugged to satiety.

For in one corner of the City Hall, the accumulation of twenty-five years of told sorrows, untold to the public or magistrate. He bound in their original form, tempting none.

Upon those blue sheets, capable of being transformed into living searching evidence upon the least provocation, are the signature of 75,000 complaining wives or husbands, of whose infelicity the world never knew, for counsel and cooling wrath saved them from the court’s airing and officials never tell.

Perhaps they are believed destroyed or forgotten, but they still remain to record mercurial pasts in case the writers of them should at any time stray from the conjugal path. They are happy now, happier, no doubt in the knowledge of a common secret to guard — but, oh, what dainty tit-bits for some neighbors to mouth, those who “hate to repeat it, but think you ought to know.” But they’re sold, so long as those who inspired them guard them so, for they’re under lock and key, and only the Inspector himself knows where he carries that key. As for morbidly approaching him, to violate their sanctity — not a bit of it — some tremble even when there is had a two dollar dog fee to settle.

“Ten are settled in my office where one reaches the court,” replied the present Staff Inspector to the questions the other day. “It is only occasionally that we cannot effect a reconciliation.”

A Peace-Making Place

Apropos of this, there has scarcely been a day for month when the court docket has not registered one or more instances of trouble between man and wife. These are scenes which the curtain shifter hides voluminously. Thirty or forty cases a week of abuse, or non-support, or bickering homes, or family cleavage are hidden from the public, hidden gratefully, for then they can still face the world. There’s suffering and tragedy recounted in that office wholesale, but too, there are smiles of reconciliation and happy thanks are returned.

An instance: A nurse and a young doctor ran away, and married in private and hid themselves. But the aunt knew there could be no money, and she wanted the girl’s happiness. So she sought the aid of the department. A telegram for a private nurse was inserted in a daily paper, a ruse but the girl through necessity answered it.

Materially this department exists for the suppression of scandal and the protection of women from themselves, their husbands, and, above all, from the busy-body world, if only they will allow the inspector to keep the door closed from the morbid. And, above all, the scenes behind he court exist for the protection of those upon whom public leaches would prey and humiliate, or for those upon whom troubles have been thrust blamelessly, and who would take the sanest way out. ♦ — G. E. Morton.