From the Toronto Star Weekly, February 21, 1914

Small Sums risked by Regulars in Public Seats

By Leo Devaney

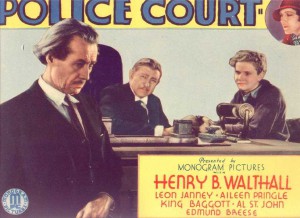

Just the other day a man who obtained food from one of the free missions in the city of Toronto was arrested as he was about to enter a picture show. He appeared in the Police Court charged with vagrancy, was convicted, and is now serving a term of thirty days in jail. The magistrate decided that any man who had money to go to a place of entertainment and then begged for food was a vagrant.

Just the other day a man who obtained food from one of the free missions in the city of Toronto was arrested as he was about to enter a picture show. He appeared in the Police Court charged with vagrancy, was convicted, and is now serving a term of thirty days in jail. The magistrate decided that any man who had money to go to a place of entertainment and then begged for food was a vagrant.

If that man had only known he might have obtained the amusement his nature craved in the very court room where he was sentenced. Toronto is fairly well supplied with theatres. For those who like a burlesque show, the theatrical managers have supplied two houses. Two or three other theatres provide vaudeville bills, while King street has its places where musical and light comedy shows are given, and even the melodrama — the villain-still-pursued-her kind of a play — is provided. But every day the Toronto Police Court provides a hodge-podge of all of them with Colonel George Taylor Denison as impresario and Crown Attorney J. Seymour Corley to supply the lights and shadows which is one of the prominent features of every well-conducted place of amusement.

Should one’s fancy turn to the more humorous side of the theatre, not educative or enlightening but more or less amusing, such as burlesque, one may see a Hebrew-Irish dialogue that will far outshine the “canned” variety offered in the different burlesque houses. It outshines it because it is spontaneous: because there is something at stake and because it is not rehearsed and carried out for forty weeks of every year. The Irish policeman is looking for credit: the Hebrew who fractures Toronto’s bylaws is looking for an acquittal, knowing that if he is allowed to go, even on remanded sentence, he saves the amount of the fine.

Monologue Artists

The Police Court has its monologists: well-known characters who are frequently in the hands of the police for minor offences and who have always a smooth, running story to explain their fall from grace. Their versatility is shown by the number and variety of yarns they tell, and for wit and earnestness of expression they are far and away ahead of the men who lean over the footlights and do their best to draw a “hand” by some near-clever line of chatter.

To those who like to see their fellow creatures in trouble, and who visit the theatre with the intention of witnessing a heavy melodrama, the Police Court provides much to interest them. Why pay to go to the theatre, sit through four acts to hear how a man beats his wife and forces her out into the street with her child, when one can see the real thing, “life as it really is,” without any of the sham of stage properties, and hear the impresario dispense with the whole case in seventeen and one-half minutes? And as a fitting background for the burlesque, the melodrama, and the rest of the serio-comic offerings in the Police Court are the rows of benches back of the wire-topped dock. Every day sees the same faces with the same expressions watching their less fortunate brothers and sisters, brought up, their cases heard, and justice dealt them.

Romance received a rude shock when it was decided to hear the women’s cases in a separate court. Under existing conditions a man who assaults his wife appears before Colonel Denison in the ordinary Police Court, but should two women go forth to battle over some modern Young Lochinvar their troubles are heard before a selected audience composed of women from different societies, a few lawyers, and an odd “mob sister” or two, who chronicle the cases for the readers of this particular brand of “news.” Although much of the glamour which attracted the species of male who frequents the Police Court disappeared with the removal of women’s cases to another court, the action of the authorities failed to check the daily gathering. They come early and they stay late, and so practiced have they become through years of association with the Police Court that any of the regular, old-time habitué will tell you before a case is half over just what the magistrate’s decision will be. And they frequently hit it right.

Visitors’ Row

A newspaper man strolled over to the “Visitors” Row” the other day and watched those who had assembled. As he stood he saw two men whose faces were familiar to the constable at the door passing coins to each other.

“Matching coins?” he asked.

“Nix: bettin’ on the decisions.”

“What’s the idea?”

“Well, we listens to the evidence a while, then I bes Shorty or Shorty bets me what’s goin’ to happen to the guy. Now watch, I’m bettin’ him a cent that this case will be remanded till called on. D’you want to come in?”

The reporter didn’t.

“How do you stand as a rule, when the day’s gambling is done?” he inquired.

“Well, I beat Shorty for six cents yesterday, an’ I’m four cents to the bad on today’s results.”

As the court adjourned while the magistrate went into another court one of the gamesters explained to the reporter why and how he happened to become a frequenter of the Police Court. His own words are more expressive than any paraphrase.

“Y’ see, I work, I do. I’m an insurance agent. I sell insurance that anybody can take. Y’ pays ten cents down and ten cents every month. It’s called industrial insurance and you can find men sellin’ it all over the city. In my line we can do nothin’ in the mornin’s but we have to be down there just the same at the office. As soon as we report to the manager we come over here and stay here until court is over.”

“How about these other fellows here — what do they do?”

“Well, some of them work and some of them don’t Some of them work in picture shows where they don’t have to show up until afternoon, and the others work in poolrooms. Ther’ ain’t nothin’ to do in the mornin’s so we come over here. Might as well be here as freezin’ on the street.”

“Whaddya bet on the next one, Shorty?” ♦