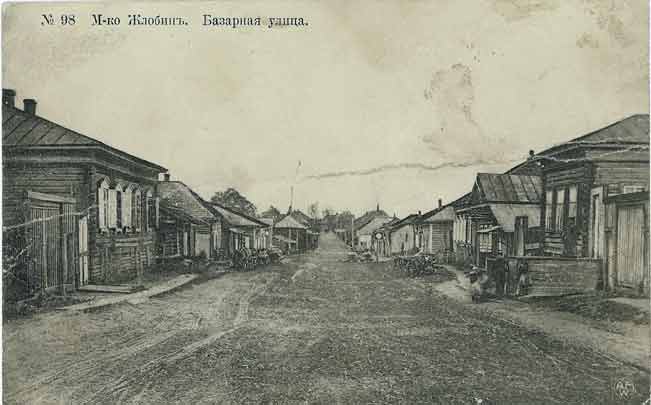

Sometime between 1905 and 1908, my mother’s grandparents said goodbye to their parents and their village of Zhlobin, Belarus, and brought their children with them to Canada. For decades, although they were divided by a wide gulf of geography and history, family members sent letters in Yiddish back and forth between the Old World and the New. Contact was broken during the Holocaust era. I can picture my grandparents, Isaac and Esther Naftolin, may they rest in peace, waiting anxiously for letters that would never arrive.

Miraculously, a newly released Soviet Jew, passing through Toronto in the 1970s, made some inquiries on behalf of friends left behind, and contact between the Canadian and Soviet branches of our family was re-established. In 1988, while engaged in family tree research, I discovered that a cousin in Toronto, a generation above me, had been corresponding in Yiddish with an elderly relative in Russia. I decided to take advantage of the opportunity.

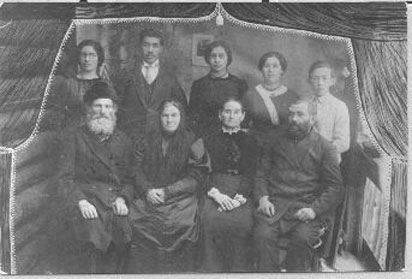

Binyamin Rubinavitch with 2nd wife Shaindl, and son Velvel and his wife Tsirlaya; five of V&T's six children (back row).

Obtaining an address in Cyrillic script, I penned a brief letter in Yiddish with the help of my cousin and mailed it along with several old family photographs. Months later, a response in Yiddish arrived from the daughter of the woman to whom I had written. “I am sad to say that my mother died on December 30,” my Russian cousin Bella Gintsbourg wrote. “I studied the photographs you sent with tears in my eyes. Unfortunately, they arrived after my mother had died. My mother used to cry when she looked at the old pictures of her family in America.”

Still, Gintsbourg was able to identify all of the unknown faces in the old family photographs I had sent her. She also was able to relate the fate of our family’s ancestral village. “All Jews were executed in Zhlobin on April 12, 1942, on the first day of Passover,” she reported.

“They were buried in a mass grave and now there is a monument there.”

I learned much from that first letter from Bella Gintsbourg. “Write to us again and don’t forget,” she closed. “Write in English; it will be easier to read. I kiss you and send heartfelt regards.”

Thus began a prolonged exchange, with letters leaving Toronto in English and arriving from the former Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in Russian. Through this correspondence, I learned first hand of the many difficult choices that politics has forced upon the Jews of the former Soviet empire.

“We are very excited that you are showing us the roots of our family,” Gintsbourg wrote in May 1990. “I tried to research the family tree long ago. I went to Zhlobin, but events like revolution and war destroyed the archives there.” According to Gintsbourg, her parents had survived because her grandparents had left Zhlobin for Leningrad after the Revolution of 1917 “in order to give the children a proper education.” Before the German siege of Leningrad during World War II, they moved to Novo Sibersk in Siberia. “It is amazing to think how we have grown up in absolutely different environments and lived absolutely different lives,” she wrote in October 1990.

In her letters, Gintsbourg admitted that circumstances were forcing her and her husband to leave the country along with many of their Jewish friends. In their early sixties, with only a few years standing between them and their retirement pensions, they felt too old to start a new

life elsewhere, but what choice did they have? They had applied to emigrate to the United States, she said, but had received no reply. Their son and his family were living in a transit camp in Italy; perhaps they would go to Israel, perhaps Germany to be near their son.

Upon investigation, immigration to Canada was not a feasible option for the Gintsbourgs. However, members of our Canadian family set up a fund to help them. Reading reports in the winter of 1991 that the food supply in Leningrad was unstable, we asked what we could send them. “We are in good health,” came the reply. “It’s not true that we don’t have enough food. There are restrictions on meat, butter, sugar and so on, but we have everything we need.” Besides, they added, most packages sent to their country never reach their intended destination.

Ironically, Bella Gintsbourg and her husband, Volodya, wanted to send us a package: some family prayerbooks dating from 1878. They arrived in August 1991, just as news broke of the hardline coup against Soviet leader Mikhael Gorbachev. As events unfolded in Moscow over the next few days, several relatives in Toronto were intensely and somewhat guiltily preoccupied with the fate of our cousins in the crumbling empire. Had we done everything possible to help them? Would they still be allowed to leave?

Their next letter reached us in September around Rosh Ha-Shana, the Jewish New Year. “Thank God the horrible events of August are over. The situation here is unpredictable at best. It seems most unfortunate for us, at our age, that everything is so indefinite and that a critical situation may arise again at any moment.”

That spring, the Gintsbourgs made an exploratory trip to Israel, where they were repeatedly advised against making aliyah (immigrating) because of the difficulties of finding jobs and affordable housing. So they chose to go to Germany instead. Their next letter, postmarked from Dillenburg in the German Republic, was an unhappy one. Although officials had assured them there was a Jewish community in a nearby town, upon arrival they found that no Jews lived in either city. “We found it very hard to get an apartment, since no one wanted to rent to us. We found that everything we heard in Russia about how Germans want to take in Russian emigrants was wrong. Nobody needs us here.” Living on social assistance, they found even a visit to their children and grandchildren in Italy beyond their means.

After eight months, they emigrated to Israel. Their next letter was postmarked from Bat Yam, the Tel Aviv suburb where they had settled into an apartment. Life was a bit easier but still no bed of roses, they wrote; somewhat stoically, they didn’t elaborate on their complaints. In the last letter that I received from them, they expressed the opinion that the political uncertainty of their Soviet homeland had robbed them of the tranquility they had hoped for in their remaining years.

That was in 1993. I wrote back after a few months but the post office returned my letter unopened. Evidently, the Gintsbourgs had moved and had left no forwarding address. On a visit to Israel in 1994, I tried to phone them but found they were not listed in the phone book. Was our correspondence to terminate so abruptly? Would there be no meeting between two branches of a family that had separated nearly 90 years before?

LAST YEAR, the week before Passover, it was my good fortune to be in Israel again. While in Jaffa, a town midway between Tel Aviv to the north and Bat Yam to the south, I asked a taxi driver to take me to the last known address I had for the Gintsbourgs in Bat Yam. It was a spur of the moment thing. I didn’t know what I would find. But I considered it a very good omen that the taxi driver was friendly and could speak Hebrew, English, Yiddish and a smattering of Russian, remembered from his childhood.

We found the apartment block; another name was on the mailbox. Still, we entered the dim corridor and climbed the stairs. I knocked on the door, heard a woman’s voice, and said:

“Gintsbourg? Bella?”

“Da,” came the response, then some words in Russian. My driver took over. I heard him say my name and explain something about a cousin from Canada. The door was opened to reveal my cousins, Bella and Volodya, looking bewildered.

Bella stared intently at me as if making sure I resembled the photograph I had sent. I probably stared just as intently back at her. We hugged like strangers. This was possibly the first time the two branches of our family had made direct contact in almost 90 years.

We were invited in. I was directed to the most comfortable chair in the apartment as we attempted small talk in Russian and Yiddish through the overtaxed linguistic conduit of Yiza, my driver-translator. Bella poured some tea. Volodya, meanwhile, began straightening books and pockets of clutter on this shelf and that.

“Yiza, tell them I was in Israel two years ago but couldn’t find their phone number.”

A moment later I heard: “They say they’re not listed in the phone book because they took over the phone from the previous tenant. They want to know, how is your mother?”

“She is fine. Thank God. How is their son in Italy?”

If Yiza minded being the conveyor of small talk in three languages, scrambling here for a phrase in Yiddish and there for a word in Russian, he did not show it.

It amazed me that after three years in Israel, the Gintsbourgs spoke almost no Hebrew. Since they are retired, they live in an isolated community, far from their grandchildren, interacting primarily with other Russian emigres. I felt extremely lucky that my great-grandparents chose Canada.

The visit was short and sweet. As I was leaving, Bella and Volodya gave me their phone number and a promise that they would write. In return, I gave them a bottle of the Bronfman’s own Seagram’s Whiskey that I had brought from Canada on a hunch that it might come in handy. It did. ♦

© 2000

Visit the All-in-One Sketch of the Rubinoff-Naftolin Family Tree