Exclusive Report, February 3, 2013

Former Toronto Mayor David Crombie easily charmed a full-house audience at a January 30th meeting of the North Toronto Historical Society in Northern District Library.

Former Toronto Mayor David Crombie easily charmed a full-house audience at a January 30th meeting of the North Toronto Historical Society in Northern District Library.

Although Crombie’s advertised topic was “North Toronto 1912, Then and Now,” references to North Toronto were few and far between. But it didn’t seem to matter to the appreciative audience that filled the auditorium. Crombie focused on the social and technological changes of the last century, spicing up his insightful talk with delightful anecdotes from his years (1972 to 1978) as Toronto’s so-called “tiny perfect mayor.”

Toronto experienced “amazing growth” from the late 19th century onward, Crombie related. In 1881 its population was 30,000 and in 1901 it was 205,000. Fuelling this growth was a steady stream of immigrants, extending from the early 20th century to modern times, that “transformed the demographic basis of the city.”

The railroad was a powerful engine of social change in the late 19th century as was the automobile in the early 20th century. “In 1907 there were 1,500 cars in Toronto, in 1916 there were 10,000 and in 1926 there were 80,000,” he said.

The city was shaped by widely-held “social gospel” that spurred the introduction of a palette of social services and public-minded institutions such as Settlement House, which helped new immigrants adjust to life in Canada. Another aspect of the social gospel was the Lord’s Day Act of 1906, which ensured the sanctity of Sundays in the city. Businesses, theatres and bars were shuttered on Sunday and even playground swings were locked up until well into the postwar era. “It was 1952 when Allan Lamport was elected on Sunday sports for a few hours,” Crombie said.

The social gospel also produced the Temperance Act, through which sections of Toronto, including West Toronto where Crombie grew up, were designated as “dry” (alcohol-free zones). As mayor, he participated in a vote to repeal West Toronto’s dry status. “It was a bit of a struggle,” he confessed with a laugh. “Ten minutes before the vote, in walks (temperance activist) Bill Temple, and he sat down across from me and looked into my soul. To my (everlasting) discredit I couldn’t get my arm up, coward that I am. The power of the temperance movement was still in me.”

The social gospel also produced the Temperance Act, through which sections of Toronto, including West Toronto where Crombie grew up, were designated as “dry” (alcohol-free zones). As mayor, he participated in a vote to repeal West Toronto’s dry status. “It was a bit of a struggle,” he confessed with a laugh. “Ten minutes before the vote, in walks (temperance activist) Bill Temple, and he sat down across from me and looked into my soul. To my (everlasting) discredit I couldn’t get my arm up, coward that I am. The power of the temperance movement was still in me.”

The First World War was a heroic adventure, at first, that fit in with Toronto’s longstanding military tradition, Crombie said: “It was going to be a three-month war.” But it quickly bogged down into a series of military horrors from Ypres to Vimy Ridge — where Crombie’s own grandfather was killed and buried. “My mother used to say, ‘Some lunatic shot a Duke and I lost my father forever.’” For many others the Grim Reaper came in the form of the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918.

After the First World War the city began a long-term planning exercise of the waterfront that resulted in the establishment of Sunnyside beach and amusement park, the Yacht Club, the island airport and other elements. The telephone, air travel, women’s voting rights, the radio, silent and talking motion pictures and other inventions and innovations helped to propel the era’s rapid social change.

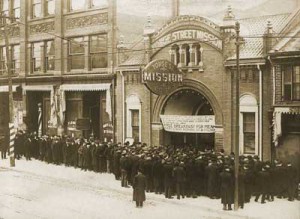

The 1930s brought the Depression and its soup kitchens, hunger marches, vast unemployment and “the pogey.” Then came the Second World War and, in its aftermath, perhaps the most enormous change of the past century: the rise of the suburbs and the Baby Boom generation.

The 1930s brought the Depression and its soup kitchens, hunger marches, vast unemployment and “the pogey.” Then came the Second World War and, in its aftermath, perhaps the most enormous change of the past century: the rise of the suburbs and the Baby Boom generation.

Crombie spoke about the reform movement of the 1970s of which he was a leading proponent, and the height restrictions on new buildings that helped preserve the character and fabric of the city’s increasingly threatened neighbourhoods.

He also recalled escorting Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip to the grand opening of the Sheraton Hotel across from City Hall. “Did the Mayor have an official chain of office?” the Queen wanted to know. City officials suddenly remembered that there was indeed such a ceremonial chain but it had been forgotten in all the excitement. “Yes we do,” someone — perhaps Crombie himself — explained to the Queen, “but it’s worn only on special occasions.”

Crombie’s conclusion seemed to be that the more things change, the more they stay the same. “If I have any message, it’s that if you look at the history books and the nature of city planning . . . everything is new again,” he said. “The basic DNA of Toronto is operating today as it was 100 years ago.”

The honour of introducing Crombie and thanking him afterwards went to Lynda Moon, president of the North Toronto Historical Society. “African Canadians in the War of 1812″ is the topic of the Society’s next meeting at the Northern District Library on February 27, 7:30 p.m. ♦

© 2013

Photos: Military parade on Yonge Street, 1915 (left) and soup kitchen on same street, 1930. Both photos show the Yonge Street Mission and are courtesy City of Toronto Archives (citations to come). Photo of David Crombie, 2010, courtesy BlogTO.