Fifty years after the Dead Sea Scrolls first came to light, biblical scholars around the world are preparing for a major conference on the scrolls that is set to roll — or unroll, as the case may be — July 20 to 25 (1997) at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Fifty years after the Dead Sea Scrolls first came to light, biblical scholars around the world are preparing for a major conference on the scrolls that is set to roll — or unroll, as the case may be — July 20 to 25 (1997) at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

While the scrolls have been the focus of scholarly gatherings before, this one promises to be special, and not just because it marks the jubilee of the discovery of the first seven scrolls in a cave in the cliffs at Qumran, above the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea in 1947.

For once, the field of study surrounding these ancient manuscripts seems remarkably free of the scandals, secrecy and sensationalism that have plagued it for decades. Until relatively recently, an inner circle of scholars maintained an obsessive stranglehold on the scrolls; it was broken only when some renegade academics helped smuggle some pirate editions into print about 1990. Since then the Oxford University Press has published authorized facsimile editions of almost all of the scrolls and reconstructed fragments, except for those still in futile jigsaw-puzzle condition.

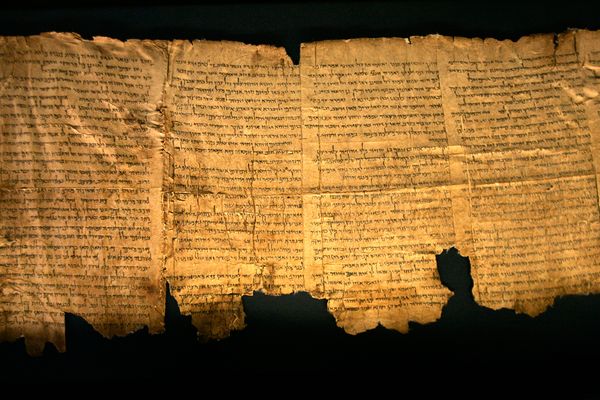

Organizers have sought to make this a large-scale public event open to all. The Israel Museum, where several of the scrolls are on permanent dispaly, is mounting three special exhibits. More than 40 international authorities are preparing to deliver specialized academic papers. One of the more technical sessions focuses on innovative approaches like carbon-14 dating, analysis of ancient inks, examination of the DNA of animal-skin parchments, and digitized computer enhancement of difficult sections of text, a technique that can radically improve legibility. There is also much of a general and cultural nature. As a preliminary program indicates, one of the non-technical sessions involves “a discussion by novelists, sociologists and psychologists of the mystical dimensions of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls as expressed in popular culture.”

According to planners, the opening ceremony will be a high-profile state occasion with the Israeli prime minister and many dignitaries in attendance as well as musicians and dancers to set a festive mood. “At this point we have good reason to be celebrating,” said Hershel Shanks, editor of the popular U.S.-based journal, Biblical Archaeology Review. “It’s a wonderful time for the scrolls. Research is burgeoning, a lot of younger scholars are involved, the scrolls are now open to everyone, publication is proceeding apace, and we’re getting a better understanding of them every day.”

Lawrence Schiffman, the Edelman professor of Hebrew and Judaic studies at New York University who is part of the congress’s academic planning committee, also sees reason for some jubilation at the jubilee: “What this conference is celebrating is the fact that after all the troubles associated with the scrolls, this is really a field that is now going in the right direction.”

Certainly the two Bedouin shepherds who uncovered the first seven, nearly intact scrolls in a cave in 1947 while searching for a lost goat could not have prophesied the immense importance of the find to our understanding of Second Temple-era Judaism and the immediate pre-Christian era. Between 1952 and 1956 ten more scroll-bearing caves were discovered, both natural and manmade, bringing the number of found scrolls to about 850.

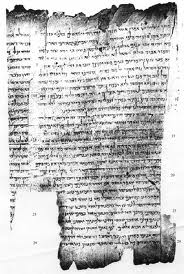

To categorize them by content, roughly one-third are biblical texts, representing every book of the Hebrew Bible except Esther. Another third are post-biblical and apocryphal works composed by outsiders to the Qumran sect: for example the Temple Scroll, at 10 metres the longest scroll, speculated to be an excluded sixth book of the Torah. The last third are mostly works composed by sect members, like the Manual of Discipline, which lays out the rules of the religious commune.

Then there is the Copper Scroll, uniquely different at a glance since it is written on copper foil, not animal parchment like the others. The Copper Scroll is not a Biblical or literary work. It is a treasure list that dryly enumerates 64 locations of hidden massive caches of silver and gold. Archaeologists speculate that Israelite tax collectors, unwilling to bring the annual tithes to Jerusalem during the Roman siege, dutifully divided and hid the bounty instead. Despite several treasure hunts, not one shekel of it has surfaced.

What, in essence, do these 850 crumbling parchments tell us? Predating previously-extant Biblical texts by at least a millenium, they illuminate the little-documented period of Judaism between the close of the Hebrew Bible in the 5th century BC and the compilation of the Mishnah, the book of Jewish oral law, about 220 AD. As well, they underscore the deep theological connections between Judaism and early Christianity.

“The scrolls tell us that ideas like the expectation of a messiah and the Son-of-God concept were floating in the air back then — they were part of Judaism,” Shanks said. “As many scholars now realize, if you want to understand Jesus you have to understand the Judaism of the era.”

Since multiple and differing versions of the books of the Hebrew Bible were found at Qumran, it’s now commonly recognized that these books did not maintain an unvarying literary form since their inception, as Jewish normative tradition insists. “The scrolls are sometimes perceived as threatening the sanctity of the Hebrew Bible, and it’s unquestionably true that the authority of the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible has been diminished,” Shanks said. “But that only means we have better texts, so it’s actually a wonderful development.”

Besides the famous Dead Sea scrolls, congress participants intend to focus on three lesser-known groups of documents found in the region. The additional collections are the scrolls found at Wadi el-Daliyeh, north of Jericho, dating from the 4th century BCE; the various Bar Kochba documents found along the shore of the Dead Sea, dating from the time of the Jewish rebellion of 132 to 135 BCE; and the Masada texts, which predate Rome’s capture of that Jewish mountain fortress in 73 CE. “All these things, whether they’re biblical texts or post-biblical literature, need to be integrated together to help us reconstruct the history of Judea in ancient times,” Schiffman said.

Participants also intend to focus on yet another highly relevant set of documents. This set includes the Fragment Of A Zadokite Work (also known as the Damascus Document) and other items among roughly 200,000 medieval Judaic manuscripts and letters retrieved from a genizah — a hidden chamber — in Cairo’s Ben Ezra synagogue about 1897.

One of the first manuscripts pulled from the Cairo Genizah, the Fragment Of A Zadokite Work was a medieval copy of an unknown work written much earlier that describes the origin of the Sadducees, a Jewish priestly sect from the time of the Second Temple. Archaeologists later found 10 manuscripts of the same document in one of the 11 known scroll-bearing caves at Qumran.

Until recently, the consensus among biblical scholars was that the Essenes, a Judaic religious sect of extreme piety and asceticism, were the faction that had kept a library of some 550 scrolls in Cave 4 at Qumran and had stashed more than 300 other manuscripts in other caves when the Romans attacked their isolated camp in 68 AD. But the Fragment Of A Zadokite Work and the Halakhic Letter — a scroll that hit the scholarly community like a bombshell when it was made public only in 1984 — offer convincing evidence to Schiffman and others that it was the Sadducees, not the Essenes, who established the large monastic settlement on the heights above the Dead Sea, the excavated ruins of which tourists may inspect today.

A Jewish priestly class, the Sadducees were loyalists of the Zadokites, the First Temple-era priestly family that lost control of the Jerusalem high priesthood about 152 BC. Qumran’s mystery sect set up camp only a year or so later, archaeologists claim.

Medieval copies of other Dead Sea works found in the Cairo Genizah include six fragments of Ben Sira, a “wisdom text” (like Proverbs) composed in 180 BC. Previous to their discovery, no Hebrew text of Ben Sira was known to exist; we had it only in Greek. Later, pieces of the manuscript turned up at Qumran and a version nearly one-third complete surfaced at Masada. Between the Cairo, Qumran and Masada copies, archaeologists have managed to piece together the full Hebrew text.

To highlight the importance of the genizah documents to scrolls research, the Israel Museum is mounting a special exhibition to commemorate the 100th anniversary of their discovery by Solomon Schecter, a Cambridge professor. The museum is mounting two other related exhibitions. A Day At Qumran concentrates on the sect that variously composed, copied and collected the scrolls, while the Architecture of the Shrine Of The Book focuses on the museum’s distinctive building in which several scrolls are displayed.

As well, the Israel Antiquities Authority is presenting an exhibit on the Conservation and Preservation of the Dead Sea Scrolls at the Rockefeller Museum in East Jerusalem.

No matter how thorough their scientific training, some scrolls scholars do not scoff when asked about the so-called “curse of the scrolls.” Too many people associated with these revealing and revered ancient manuscripts have succumbed to alcoholism, severe mental problems, poor health and premature death. Neither Schiffman nor Shanks dismiss the curse as baseless superstitious lore. “I was attacked by the curse,” Shanks said. “Months after we succeeded in ‘liberating’ the scrolls I was in a critical care unit of a hospital with a shunt in my head. I had suffered a hemorrhage.”

Schiffman further associates the curse with a torrent of bad scholarship and sensational publicity comparable to the hype surrounding the Kennedy assassination or the now-discredited shroud of Turin. He cites the case of two American rabbis who made headlines several years ago by claiming to find references to Jesus in the scrolls. “What they actually found were references to Joshua from the Book of Joshua. But the rabbis didn’t know it, and the story got into the Los Angeles Times.”

The curse of the scrolls may also be defined as “excess — loss of self-control,” according to Schiffman. “People write all these strange things and rush them to market for a lot of strange reasons. That’s what we’ve been seeing.”

He seems convinced, however, that the Jerusalem gathering will dispel the curse once and for all, and set the field on a path towards a stable scientific future. ♦

Originally appeared in the Globe and Mail. © 1997 by Bill Gladstone

* * *

Dead Sea Scrolls were preserved in Qumran caves

Fifty-five years after a Bedouin shepherd went in search of a lost goat and found seven ancient scrolls in a cave at Qumran, we know surprisingly little about the Jewish sect that produced the roughly 850 scrolls that were eventually found in 11 caves above the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea between 1947 and 1956.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are regarded as a major scientific discovery of the last century, just as their suppression for decades by a secretive clique of Christian scholars ranks as one of the century’s biggest academic scandals. But all that is history, now that almost all of the scrolls have found their way into print. These crumbling parchments have been of immense importance to our understanding of Second Temple-era Judaism and the immediate pre-Christian era.

The consensus among biblical scholars is that it was the Essenes, a Judaic religious sect of extreme piety and asceticism, who produced the scrolls, keeping a library of some 550 of them in Cave 4, and stashing hundreds of others in various caves when the Romans attacked their isolated camp in 68 CE.

New York University Professor Lawrence Schiffman, however, offers a thoughtful hypothesis that it was the Sadducees, loyalists of the First Temple priesthood, who established the large monastic settlement on these heights above the Dead Sea, the excavated ruins of which tourists may inspect today. Qumran’s mystery sect set up camp about 150 BCE, only a year or so after the the First Temple-era priestly family lost control of the holy franchise, some archaeologists claim.

New York University Professor Lawrence Schiffman, however, offers a thoughtful hypothesis that it was the Sadducees, loyalists of the First Temple priesthood, who established the large monastic settlement on these heights above the Dead Sea, the excavated ruins of which tourists may inspect today. Qumran’s mystery sect set up camp about 150 BCE, only a year or so after the the First Temple-era priestly family lost control of the holy franchise, some archaeologists claim.

An audiovisual presentation in the newish Visitor Centre at Qumran paints a picture of strict religious devotion by a community consisting entirely of celibate males.

“Think of a Catholic monastic order with a strict rule, then you’ve got some concept of daily life here,” said our guide, Mike Rogoff, during a recent tour. “Vows of purity, chastity and poverty — all of these applied.”

But archaeologists are puzzled that some women and children were also apparently buried in the communal cemetery.

Many of the rules that guided the Qumran community were laid out in the Manual of Discipline, one of many scrolls composed by sect members. Another, the War Scroll, challenges the consensus opinion that the sect was pacifist in nature. The War Scroll is a combat manual that describes an apocryphal battle between the Children of Light (the Qumran sect) and a metaphorical enemy, unidentified in real terms, called the Children of Darkness.

Obviously, the Qumran sect were millennialists.

“They saw themselves as the Sons of Light — the forces of good fighting against the forces of evil,” Rogoff said. “There was supposed to be seven battles fought — I always think of this as an eschatological world series. Three would be won by the Sons of Light and three by the Sons of Bad. And then the Sons of Good would win in the end. The scroll is a game plan for an end-of-the-world battle.”

We stroll through the rebuilt foundations of an aqueduct, reservoirs, cisterns, observation tower, kitchen, pantry, dining hall, mikvah, pottery workshop and the rectangular scriptorium. “This is where they actually wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls,” Rogoff explained. “They found ink-pots, one of bronze and one of clay, and a sort of desk.” (Visitors may also hike along mountain trails and explore some of the many caves in the area.)

Roughly speaking, about one-third of the 850 scrolls are biblical texts, representing every book of the Hebrew Bible except Esther. Another third are post-biblical and apocryphal works composed by outsiders to the Qumran sect, like the famous Temple Scroll. The last third are mostly works composed by sect members. They were written on leather, papyrus and — in the singular case of the Copper Scroll — copper. Many, including the War Scroll and the celebrated Isaiah Scroll, are on view in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum, which affords them the reverential treatment they deserve.

As 19th-century geographer George Adam Smith observes, the biblical-era history of the Dead Sea area may be said to begin with Sodom and Gomorrah, and to end with the massacre at Masada. The barren desert landscape around this unique, low-lying lake also evokes images of the Ein Gedi oasis and Ezekiel’s vision.

Ever since 1947 — precisely contemporaneous with the founding of the modern Jewish state — we also associate the region with the extraordinary discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the many aspects of Jewish history and writings that they illuminate so richly. ♦

© 2002