Standing in an underground chamber boasting Roman pillars and cobblestones from Herodian times, the group of about 40 tourists in Jerusalem’s Western Wall tunnel, including myself, listened as the guide explained that we had reached the end of the tour and had to retrace our steps back some 450 meters to the entrance. This was three months ago.

Standing in an underground chamber boasting Roman pillars and cobblestones from Herodian times, the group of about 40 tourists in Jerusalem’s Western Wall tunnel, including myself, listened as the guide explained that we had reached the end of the tour and had to retrace our steps back some 450 meters to the entrance. This was three months ago.

As most of the people began heading back through this extraordinary series of subterranean passages, I noticed the locked chain-link fence ahead.

“Where does that lead?” I asked the guide.

“That’s an exit. It goes up to the Via Dolorosa. The last time we tried to open it, the Muslims started to riot. Now we keep it closed.”

So back we trod, through the various halls, arches and other constructions of Byzantine and Mameluke origin.

Again we passed the Great Stone, a 400-tonne massif big as a house. The ancient Israelites were obviously thinking of permanence when they laid down this stone as part of the foundation for the Temple Mount. The Romans couldn’t budge it when they brought the Temple down in 70 CE.

Again we passed the Great Stone, a 400-tonne massif big as a house. The ancient Israelites were obviously thinking of permanence when they laid down this stone as part of the foundation for the Temple Mount. The Romans couldn’t budge it when they brought the Temple down in 70 CE.

Back, back we walked, retracing our steps through time and space. Again we passed the Great Hall, with its excellent scale model of the Temple, and Wilson’s Arch, once part of a royal bridge connecting King Herod’s palace to the Temple. Again we heard the reverberating hallelujahs and lamentations of pious Jews in prayer.

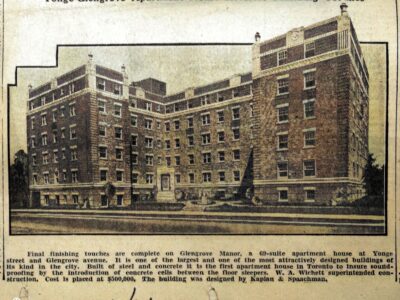

Ascending the stairs, we reached the entrance and exited the glass doors into the bright sunlight as another group readied to make the descent into history. Some 400 visitors pass through here each day, but tourism officials assert the figure could easily surpass 1,000 if the Via Dolorosa exit was used.

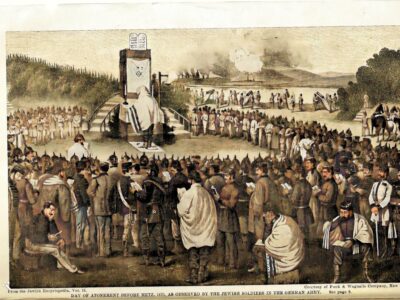

The Western Wall tunnels are a tourist attraction of special significance to Jews. For centuries, under Muslim and British rule, they were buried, filled with debris, all but forgotten. Serious excavation began only after the Jews won back the Old City in 1967. Since the tunnels permit us to glimpse the two-thirds’ portion of the Western Wall that is below ground level, they are a symbol for us that we must look deep beneath the surface of things in order to appreciate our own history and identity as Jews.

Last month (September 1996), the Via Dolorosa exit was opened and deadly riots ensued. Hopefully, this tragic turn will not deter even a single visitor from seeing the tunnels which, contrary to some distorted claims, do not undermine the El-Aqsa Mosque or any other structure.

Last month (September 1996), the Via Dolorosa exit was opened and deadly riots ensued. Hopefully, this tragic turn will not deter even a single visitor from seeing the tunnels which, contrary to some distorted claims, do not undermine the El-Aqsa Mosque or any other structure.

A visit to these intricate underground passages, which offer a unique glimmer of Israel’s ancient glory, is a profound educational experience, not a political statement. No Jewish tourist should depart Jerusalem without seeing the tunnels, any more than he or she would leave without approaching Judaism’s holiest site, the Western Wall. ♦

© 1996