Dr. David Eisen had a passionate interest in the history of Toronto Jewry

From The Jewish Standard, November 1990

IT SHOULD NOT come as a surprise to those who knew him that, in his youth, Dr. David Eisen had wanted to become a professional historian. Eisen, who died in Toronto in 1988 at the age of 87, explains in his useful and interesting Diary of A Medical Student that his brother discouraged him from that path with the gloomy but realistic pronouncement that a Jew could not, back then, get a job teaching history in Toronto. Eisen, the youngest son of a Galician peddler who came to Toronto about 1902 and then brought over his wife and six children — pragmatically chose medicine instead. He graduated from the University of Toronto Medical School in 1922 and joined the staff of the Mount Sinai Hospital as Toronto’s first Jewish radiologist. However, as he declares in the epilogue to his diary, “As for myself, I have always retained my interest in history.”

That interest was certainly evident in 1946 when he convened the first meeting of what would become the Toronto Jewish Historical Society and delivered before an august gathering of scholars a learned paper on the subject of Ancient Jewish Coinage. “He was very well steeped in local Jewish history and universal history as well,” said Jack Mandell, a retired businessman who was the executive director of Associated Hebrew Schools and a member of the historical society. “Sometimes, much to my surprise, he caught me on exact dates and certain incidents and events in history, and I was always grateful for that. He could take a lot of criticism and he enjoyed it because he knew how to give it back. He always clashed with fellow member Dr. Aaron Volpe on details but that generally made the proceedings more exciting.”

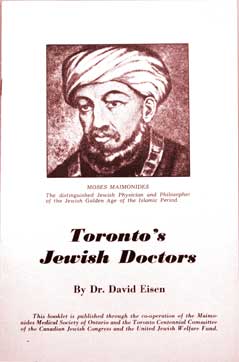

Although he was not among the first Jewish doctors to practice in Toronto, he had known many of them. In 1957, The Jewish Standard published his interesting treatise on Toronto’s Jewish Doctors; it was later reprinted in booklet form featuring on its cover a portrait of Moses Maimonides, the medieval Jewish doctor and Talmudic scholar. Of Toronto’s first Jewish doctor, Samuel Lavine (1875-1959), Eisen records that although it was “the era in which the well-established practitioner wore a high silk hat and made his rounds in a horse and carriage, not so the young doctor. In his early years in practice Dr. Lavine made his calls on a bicycle. Later, he changed to the more fashionable, but less dependable, automobile. The Jewish population at this time was about 3,000. Many people in their middle fifties and younger, some of them prominent in business and professional life, were ushered into this world by Dr. Lavine and cherish pleasant memories of this pioneer doctor.”

Although he was not among the first Jewish doctors to practice in Toronto, he had known many of them. In 1957, The Jewish Standard published his interesting treatise on Toronto’s Jewish Doctors; it was later reprinted in booklet form featuring on its cover a portrait of Moses Maimonides, the medieval Jewish doctor and Talmudic scholar. Of Toronto’s first Jewish doctor, Samuel Lavine (1875-1959), Eisen records that although it was “the era in which the well-established practitioner wore a high silk hat and made his rounds in a horse and carriage, not so the young doctor. In his early years in practice Dr. Lavine made his calls on a bicycle. Later, he changed to the more fashionable, but less dependable, automobile. The Jewish population at this time was about 3,000. Many people in their middle fifties and younger, some of them prominent in business and professional life, were ushered into this world by Dr. Lavine and cherish pleasant memories of this pioneer doctor.”

The Jewish Standard also published numerous studies that Eisen conducted over the years into aspects of Toronto’s early Jewish community. In 1965, Eisen became the chief archivist for the Holy Blossom Temple and, thereafter, the synagogue’s biweekly bulletin often carried delightful little historical pearls from him. “Toronto’s First Dentists” is the title of an article he contributed to the Jewish-Canadian dental fraternity’s Alpha Omega Review in 1967, and a researcher more thorough than I could probably uncover his name in a multitude of other publications. Thus, while occupied with a busy medical career, he established a solid reputation as a historian of Toronto’s Jewish community.

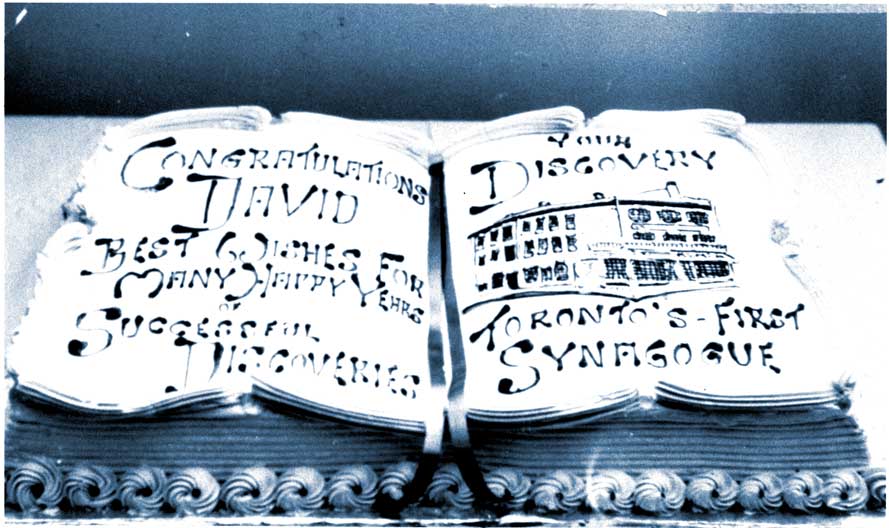

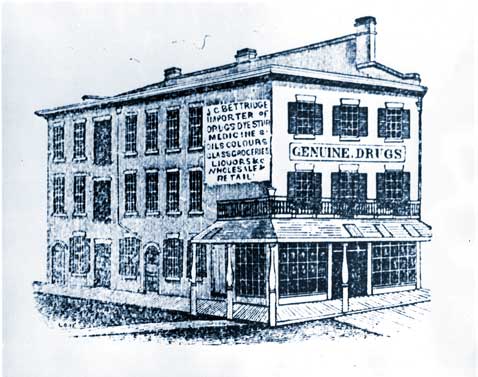

A room above Coomb’s Drugstore served as Toronto’s first synagogue, c1856-1875. Eisen found the illustration..

Among the myriad topics conquered by Eisen’s pen were Early Jewish Settlers, Jewish Pioneers in the Clothing Industry, Toronto’s First Synagogue, An Old Toronto Drug Store, The Richmond Street Synagogue, The King Family of Whitby, and How Our Temple (the Holy Blossom) Got Its Name. He made a comprehensive study of the burials in our oldest cemetery, Pape Avenue, which dates from 1849. An habitue of archives and libraries, he discovered a picture of Toronto’s first synagogue. He wrote about Rabbi Elzas, an early rabbi, and received an informative and complimentary letter from Elzas’s elderly daughter in New York. In a column on Arthur Wellington Hart, the first Jew known to live here (from about 1833), he wrote: “Those of our co-religionists who are insurance agents can now hold their occupational heads high in the knowledge that theirs is the oldest Jewish business in Toronto!”

Eisen published many important professional papers as well. In July 1925, the American Journal of the Medical Sciences carried “Malignant Tumors of the Thyroid,” the first of several articles by him to be featured in its pages. Others appeared in The American Journal of Surgery, Radiology, and the Canadian Medical Association Journal. It was in the latter publication that his unusual and quite fascinating monograph, “An Account of An Epidemic In Palestine in 1040 BC” appeared in 1948.

In this two-page study, he combined his medical training with his professed affinity for history to discuss the etiology of a plague that may have ravaged the region between Jaffa and the Egyptian border at the time of the biblical King Samuel. Discussing the vile contagion that had possessed the Philistines when the Hebrews had recaptured the Holy Ark from them through battle, Eisen — citing sources as diverse and monumental as Castiglione’s “History of Medicine,” Frazer’s “Golden Bough” and Josephus’s “Antiquities of the Jews” — presents a startlingly original hypothesis.

Noting that “the presence of the Ark seems to have had the same disastrous results on the Hebrew side of the border as in Philistia,” he suggests that the Hebrews were smitten not because they looked into the Ark of the Lord but due to the spread of “an epidemic which knows no religious or political boundaries. Assuming that the epidemic was actually a plague, it might be interesting to speculate whether the Ark itself might have been a carrier of the fleas that spread the disease.”

* * *

IN THE PREFACE to his book, The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937, which was published in 1979, Dr. Stephen Speisman called Eisen the “dean of the historians of Jewish Toronto.” Now (ca 1990) archivist for the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC), Ontario Region, Speisman seemed pleased when I told him I was writing this article, commenting that it was about time Dr. Eisen got the recognition he deserved. “He laid the foundation for a great deal of the history of our community that would be written later on,” Speisman said.

IN THE PREFACE to his book, The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937, which was published in 1979, Dr. Stephen Speisman called Eisen the “dean of the historians of Jewish Toronto.” Now (ca 1990) archivist for the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC), Ontario Region, Speisman seemed pleased when I told him I was writing this article, commenting that it was about time Dr. Eisen got the recognition he deserved. “He laid the foundation for a great deal of the history of our community that would be written later on,” Speisman said.

“As a historian, he [Eisen] was very thorough,” according to Ben Kayfetz, the retired former director of community relations for the CJC (1990). “He really researched his topics in great detail. He studied the registers and the city directories and other original sources carefully to learn more about the Jewish residents of Toronto in the early years. He had professional standards of research.”

It was those professional standards, perhaps, that readily convinced Kayfetz and the CJC to publish Eisen’s diary in the mid-1970s when a government grant became available to defray costs. Unmindful of posterity, Eisen had kept the diary between 1917 and 1922 as a personal record of his years at medical school. Half a century later, he felt, correctly, that it had worth as a social rather than a personal document, illuminative of Toronto’s Jewish community in the early decades of this century.

Kayfetz recalls that the book received favourable attention upon its publication in 1976, exactly fifty years after its author embarked upon the practice of his specialty. “It’s a very valuable book,” he comments. “He talks about the flu epidemic of 1918 and how he accompanied certain doctors on their rounds. He describes how after certain elections, the results were shown on a big screen in front of the building of the Hebrew Journal, a Yiddish daily that was then on Elizabeth Street . . . . It gives many immediate impressions of a young man at that time, uncoloured by later developments and happenings.

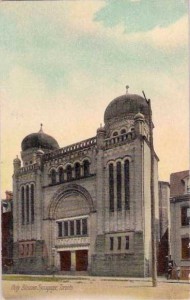

In its introduction, Eisen recalls that he attended four public schools including the Victoria Street School, of which he writes: “My main memory of this school was that from the schoolyard I could see the twin cupolated towers of the Bond Street Synagogue, one block to the east.” Through his life, the direction of his gaze, metaphysically and metaphorically speaking, never varied. Despite a hectic schedule attending classes in which he may have been called upon to dissect a rabbit or hear a professor expound on Mammalian Anatomy, he joined in a wide range of Judaic activities involving such early Jewish institutions as the Toronto Hebrew Students Association, the Menorah Society, and the Zionist Institute.

In its introduction, Eisen recalls that he attended four public schools including the Victoria Street School, of which he writes: “My main memory of this school was that from the schoolyard I could see the twin cupolated towers of the Bond Street Synagogue, one block to the east.” Through his life, the direction of his gaze, metaphysically and metaphorically speaking, never varied. Despite a hectic schedule attending classes in which he may have been called upon to dissect a rabbit or hear a professor expound on Mammalian Anatomy, he joined in a wide range of Judaic activities involving such early Jewish institutions as the Toronto Hebrew Students Association, the Menorah Society, and the Zionist Institute.

December 10, 1917: “The British capture of Jerusalem was announced today. I certainly felt a thrill when I heard about it. I was retrieving my hat and coat from the cloak-room attendant at the Reference Library and noticed the large headlines in the newspaper that he was reading. When I reached Spadina Avenue, I bought all three evening papers. . . .”

November 18, 1918: “Today I noticed in the Star Weekly an article in the form of a review of a book written by a Dr. Rihbany, a Syrian, who pleads the Arab cause and asks America ‘to save the Near East’ from the rapacious Zionists. Quite a few misleading statements were made by the reviewer, presumably on the basis of what appeared in the book. I wrote a letter to the Star criticizing the review.”

Some entries suggest the flavour of life in a city seemingly unwilling to accommodate to the growing number of Jews in its midst. “Yom Kippur today,” he records on September 26, 1917. “Lectures started but I did not attend. I spent the morning in the recently founded synagogue across the street. . . .”

Many entries in Dr. Eisen’s diary illuminate a community developing its own personality and character. Perhaps the most interesting entries are those about a city grappling with a flu epidemic that claimed 58 people in one day and closed down every dance hall and movie theatre; about the predawn firecrackers and bonfires on downtown streets upon news of the Armistice; and about Jewish life, glimpsed in passing but telling detail, at a time when a youthful Zionist movement was sparking a global Jewish spiritual and nationalistic revival.

* * *

THE FEW PERSONAL DETAILS allowed to stand are poignant. April 2, 1919: “After two years of illness, poor father died at 2.40 a.m. on April 1 . . . . It must have been a great suffering that would cause father, who normally was of a rather choleric disposition, to become, near the end, so patient, meek and gentle.” And of course, by the time the journal ends, Eisen had not yet met my father’s first cousin, Vera Alexander, a fourth-year student at University College whom he encountered at a dance in 1929 and married the following year — “the most important step in my life,” he reports in the epilogue.

THE FEW PERSONAL DETAILS allowed to stand are poignant. April 2, 1919: “After two years of illness, poor father died at 2.40 a.m. on April 1 . . . . It must have been a great suffering that would cause father, who normally was of a rather choleric disposition, to become, near the end, so patient, meek and gentle.” And of course, by the time the journal ends, Eisen had not yet met my father’s first cousin, Vera Alexander, a fourth-year student at University College whom he encountered at a dance in 1929 and married the following year — “the most important step in my life,” he reports in the epilogue.

Likewise, the diary throws little light on his years at Mount Sinai, which had only 35 beds when he started working there alongside L.J. Solway, A.I. Willinsky, L.J. Breslin and other Jewish medics whose names are still widely known in the community. Eisen became president of the Toronto Jewish Medical Association, its staff organization, in 1929. An anecdote in the epilogue of his diary suggests something of what it must have been like to be a radiologist at a time when scheduling a chest x-ray of the lungs generally signified to a patient that his doctor suspected some serious disease.

“I recall the case of a Jewish woman who came into my office with tears in her eyes and who freely vocalized her worries in Yiddish. She knew she had consumption — otherwise why would her doctor have wanted an x-ray? What will happen to her little orphans after she died? Her husband will probably remarry; and how much love will her children get from a stepmother? She almost had me crying too. When I examined her films and found them perfectly normal I could not restrain myself from telling her so, even though the proper practice for a radiologist is to report the results first to the referring doctor. Her reaction to my reassurance was remarkable. ‘What! Nothing wrong? No consumption? So what did I need an x-ray for? I just threw away ten dollars.'”

Preparing one’s diary for printing can only be an exercise in nostalgia and introspection, with perhaps more than a touch of self-aggrandizement. It must also be an occasion for marking the passage of time. Eisen does this elegantly in the epilogue when he comments that “the elapse of a half century has changed the earnest young man about ‘town and gown’ into a grizzled septuagenarian with two daughters and eight grandchildren.”

His daughters, Barbara and Joy, were that rarity among rarities, mirror-image identical twins. Both became nurses, marrying a doctor and a lawyer respectively, and producing four children each. One of the pair, my second cousin Barbara Organ, told me that her father had purchased a car when he first began to practice. This, of course, was after the era of the high silk hat and the horse and carriage, but still before the time when motorists were required to pass stringent driving tests and obtain licenses. “My father was an old-fashioned driver,” she said. “He kept his eyes on the road and never used mirrors. And that’s exactly the way he carried out his life.”

His daughters, Barbara and Joy, were that rarity among rarities, mirror-image identical twins. Both became nurses, marrying a doctor and a lawyer respectively, and producing four children each. One of the pair, my second cousin Barbara Organ, told me that her father had purchased a car when he first began to practice. This, of course, was after the era of the high silk hat and the horse and carriage, but still before the time when motorists were required to pass stringent driving tests and obtain licenses. “My father was an old-fashioned driver,” she said. “He kept his eyes on the road and never used mirrors. And that’s exactly the way he carried out his life.”

One day when her father was in his early seventies, Barbara related, he walked across the street without looking and was struck by a car. “Luckily, he wasn’t very seriously injured, but he was very shocked by this,” she said. “He was a man who had never been sick in his life. He never had smallpox even though he had diagnosed it twice. He had thought he was immortal. The day he was hit, he quit his practice. That year, he went to work on his book. When that was finished, he had achieved his life’s ambition.”

Interestingly, several of Eisen’s grandchildren seem to have followed at least partially in his footsteps. One granddaughter, Julie Organ Paradis, is a nurse. One grandson, Norman Wolfson, has completed an undergraduate degree in history at York University, having concentrated on the British mandate in Palestine. Saturday mornings he teaches grade six cheder at Holy Blossom. I visited him recently at his home in East York, and he excused himself for a moment and returned with a framed wrestling trophy that his grandfather had won in the 1920s. “He gave it to me because I was also a wrestler — I competed in the North York finals in 1975,” he told me. “He used to joke with me that when he was wrestling, if any guy had long hair like mine, he’d have used it to his advantage. It was his way of telling me to get a haircut.”

In 1977, the doctor’s daughter Barbara and grandson Michael Organ, then two years shy of bar-mitzvah age, interviewed him for about ninety minutes about his early memories and experiences. The tapes indicate someone with an eye for empirical detail, methodical in thought and speech, who never lost the rigorous scholastic habits drilled into him by an Edwardian public school education.

Arriving with his mother at Union Station as a child of three or four, he recalls, “someone made a grab for me, and I shrank away and grabbed my mother,” adding that the intruder was his father. He also describes the old, predominantly Jewish section of Toronto known as The Ward, and the “unsatisfactory” religious education he received at home from a succession of rebbes and learned rags peddlers “who worked by day and in the evening eked out a few extra pennies by teaching religious studies …. I often saw their eyes close from tiredness.”

In these tapes, Eisen divulges that he had written a series of exams to compete for one of five lucrative scholarships in history from McMaster University, which was then located in Toronto. He won the first scholarship — tuition and money for books and other living expenses for four years — but declined it on his brother’s advice and went into medicine “at the last minute.” Fortunately for Toronto’s Jewish community, however, he never turned his back on history.

* * *

BY THE TIME I became acutely interested in my paternal grandmother’s Alexander family tree and simultaneously in Toronto’s Jewish community, the Alzheimer’s disease that eventually claimed Dr. Eisen was too far advanced to allow us to meet. However, on a sunny winter afternoon in early 1987, I visited his wife, the eldest daughter of my great-uncle Harry Alexander, who had been a pioneer in the motion picture industry in Canada. Vera was also somewhat of a pioneer, having earned a degree in history and literature in the days when relatively few women had such aspirations.

BY THE TIME I became acutely interested in my paternal grandmother’s Alexander family tree and simultaneously in Toronto’s Jewish community, the Alzheimer’s disease that eventually claimed Dr. Eisen was too far advanced to allow us to meet. However, on a sunny winter afternoon in early 1987, I visited his wife, the eldest daughter of my great-uncle Harry Alexander, who had been a pioneer in the motion picture industry in Canada. Vera was also somewhat of a pioneer, having earned a degree in history and literature in the days when relatively few women had such aspirations.

She and my grandmother Dora, her aunt, had both possessed the same Hebrew name Dvorah, and I had wondered whom they had been named after. Thinking this suitable grounds for an introduction, I had phoned her, hoping she would also tell me more about the Alexanders. Offering kind regards to my father, she had invited me to visit, but had subsequently fallen ill, requiring hospitalization at the Mount Sinai. About six or eight weeks later, she sent the following note: “Dear Bill, Thanks so much to you and your dad for your lovely card of good wishes. I am home now from the hospital, ‘taking life easy.’ When you’re ready, do call me, and we can make a date for you to come and see those pictures in which you are interested.”

A thin, white-haired, aristocratic-looking lady greeted me at the door of the apartment in the well-appointed midtown building in which she had lived for some two decades. She seemed very thin and her wrists and arms a bit too brittle for comfort. She spoke with the same youthful voice that I had heard over the telephone, and even though I had known all along that she had been born in 1910, it astonished me to hear this young, enthusiastic timbre emanating from a being so advanced in years. “Yes, I was sick, and I had a pretty bad time of it, but I’m okay now, just can’t go out very much any more, except a couple of times a week to visit my husband in the hospital.”

She was very generous with me, sharing both her photographic collection and her knowledge of the Alexander family. Despite her apparent fragility, she possessed a certain grace. She produced a plate of sugary cookies and wheeled in a sterling silver tea service, pouring tea into fine china cups as if it were still only 1947 or thereabouts. She spoke a great deal of her husband, boasted of his diary and his association with the Holy Blossom, showed me scrapbooks full of his published works.

“My husband was a very meticulous researcher,” she said. “The librarians used to hate him because he made them get material from the oldest, dustiest shelves where hardly anyone ever went. He was extremely proud of some of his discoveries. Through his meticulous research, he discovered the name of the first Jewish child born in Toronto, a girl [Elizabeth Driscoll, born 1838]. He also found a picture of the very first synagogue in Toronto — the only picture that has ever come to light so far.”

And here she showed me a snapshot of a large, elaborately decorated cake in the shape of an open book, with the outline of a building done in icing on one side and some writing on the other. “I had the picture of the synagogue put onto a cake,” she explained. “This is a photograph of it.”

When I had to leave for an appointment, she seemed disappointed, and invited me to return. I was at the elevator before I realized that I had, most uncharacteristically, forgotten my overcoat.

Our next meeting, alas, was at the Holy Blossom Temple a few months later for the funeral of her beloved husband. She was in a wheelchair and it was obvious that her health and spirits had deteriorated greatly. I sent condolences and received the following prompt acknowledgement: “Our sincere thanks to you and the family for your kindness in honouring David’s memory through the contribution of ‘The Light Beyond’ to the Albert J. Latner Jewish Public Library. I know David would have liked very much to meet you and discuss your common interests. Yours, Vera.”

We never met again. I am saddened to report that, some nine months after the death of Dr. Eisen, his widow followed him into the grave. ♦

This article first appeared in The Jewish Standard (in two consecutive issues) in November 1990. © 2012 by Bill Gladstone.