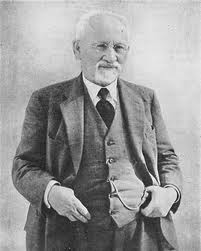

Born in Belarussia, and later a resident of St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kovno and Riga, Simon Dubnow (1860-1941) published his first essay about the Jews of Russia in 1880, and understood at a relatively early age that the subject would always be of particular significance for him.

Born in Belarussia, and later a resident of St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kovno and Riga, Simon Dubnow (1860-1941) published his first essay about the Jews of Russia in 1880, and understood at a relatively early age that the subject would always be of particular significance for him.

He wrote in his diary in 1892, “My life’s task has become clear to me: to spread historical science and work especially on the history of Russian Jews. I have become a missionary of history.”

By that time, he knew that his self-declared task was too big for one man. That is why, the previous year, he had galvanized the intellectual community with a broad public appeal for assistance in collecting and preserving source material related to the history of the Jews in Russia.

Written specifically for the Jewish Publication Society of America, Dubnow’s History of the Jews of Poland and Russia appeared in English translation in three volumes between 1916 and 1920. There have been numerous reprints throughout the century, the most recent being a re-issue by Ktav in 1975.

Avotaynu Inc., the New Jersey-based Jewish genealogical printing house that publishes this journal, has presented the latest incarnation of Dubnow’s classic in a large, single volume of 600 pages. Dr. Israel Friedlander’s original translation has been completely reset and enhanced with a more thorough index; without, however, any maps, illustrations or photographs to illuminate the text.

Dubnow’s masterful study opens with early Jewish settlements on the shores of the Black Sea, and continues methodically to the agitations, disabilities and pogroms that sparked the waves of mass exodus of the late 19th century. His special talent apparently lay in crafting a grand intellectual synthesis without neglecting the small, telling details, which he presents in their full colour. The flavour of original sources is evident on almost every page.

Reviewers have lauded Dubnow for his brilliant writing style, his clear language, his objective yet sympathetic approach to the Jewish people, his evenly-paced perspective, and his wide-ranging, sociological view of history: he does not favor economic, religious or any other aspect of history above another.

Some reviewers assert that the famous historian tended to “compartmentalize” the Jews of Russia, as if the rest of the world didn’t exist. However, this criticism seems to violate Dubnow’s own theory of Jewish history, for he had become convinced of the unity of the Jewish people, despite the seeming discontinuities of isolated regional populations.

By way of background, Dubnow believed that the diaspora “was not only a possibility but a necessity,” even as an historical inevitability. He once wrote: “A people small in number but great in quality, situated on the crossroads of the giant nations of Asia and Africa, could not preserve both its state and its nationality, and had perforce to break the barrel in order to preserve the wine — this was the great miracle of mankind.”

He differed from his predecessor, the great Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891), in positing that the core of Jewish existence was more than culture and religion; it was also the highly-developed communal structure that kept Jewish society flourishing wherever it was planted, Dubnow taught. Unlike the growing cadre of Zionists around him, Dubnow did not believe that a national territory was necessary to sustain Jewish life. However, this opinion was formed well in advance of the Nazi era.

He differed from his predecessor, the great Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891), in positing that the core of Jewish existence was more than culture and religion; it was also the highly-developed communal structure that kept Jewish society flourishing wherever it was planted, Dubnow taught. Unlike the growing cadre of Zionists around him, Dubnow did not believe that a national territory was necessary to sustain Jewish life. However, this opinion was formed well in advance of the Nazi era.

It is particularly gratifying that Avotaynu has brought out this fresh edition, considering that the Nazis seemed bent on destroying Dubnow and everything he represented. Dubnow was murdered by a Gestapo henchman in Riga in 1941; according to the Encyclopedia Judaica, his killer had been a former student of his.

Afterwards, the Nazis went to great pains to destroy him conceptually as well. They burned the third volume of his autobiography in its entirety — every last copy, it seems, but one. It turned up in 1956, allowing a complete edition of the autobiography to roll off the press the following year.

The master work of a brilliant historian, History of the Jews in Poland and Russia provides an exemplary background for researchers desirous of learning the particular social, economic, religious and other historic factors that shaped the lives of our Ashkenazim ancestors, from their earliest origins until the era of the First Great War. ♦

© 2000