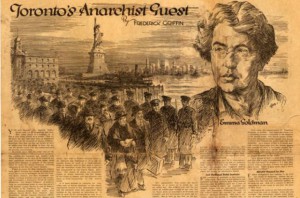

From the Toronto Star Weekly, December 31, 1926

by Frederick Griffin

You can’t imagine the gigantic United States with all its doughboys and buddies being scared of a woman. It is like a man being scared of a mouse. And yet we have the fact that they were so frightened over there by the presence of Emma Goldman, anarchist, that they put her out darkly at dead of night — and they are going to keep her out lest she should topple over the constitution and its nineteen amendments.

You can’t imagine the gigantic United States with all its doughboys and buddies being scared of a woman. It is like a man being scared of a mouse. And yet we have the fact that they were so frightened over there by the presence of Emma Goldman, anarchist, that they put her out darkly at dead of night — and they are going to keep her out lest she should topple over the constitution and its nineteen amendments.

Of course there was the other case of the Countess of Cathcart and her moral turpitude. But whereas her ladyship was finally, with much trembling on the part of the hundred per cent Americans, admitted to their midst, there seems little prospect at present of the barrier being let down for Emma Goldman, erstwhile citizeness of the free and equal republic.

Which accounts for Miss Goldman’s present brief use of Toronto as a haven of refuge from storm and stress in succession to the late Goldwin Smith, scholar, and Mrs. Pankhurst, suffragist, previous notables who gave our provincial atmosphere a temporary flavour of world’s distinction. For Emma Goldman is probably from an international point of view the world’s most notable woman, known as well in Moscow or Vienna as in Paterson, N.J. Name the others: Suzanne Lenglen, Lady Astor, Jane Addams, Queen Marie, Mary Pickford, Mrs. Pankhurst, Margot Asquith, Gertrude Ederle, Madame Curie and the Dolly Sisters — and whom else have you?

Who will say that Emma Goldman is not the most interesting and distinguished of her present-day sisterhood? She has lived more fully than most of them, rebelled more strenuously and unselfishly, suffered more vividly, thought more vigorously. Of her day and generation she is the social Joan of Arc.

Has she any regrets? She is now fifty-six and I asked her: “What of the future? What are your plans? Is your revolt over?” And she answered:

“I believe in living every minute to the fullest extent. I let time take care of itself and never give a thought to the future. My immediate plans are to finish my lecture tour of Canada and then go to Europe for two years to write my autobiography. After that, I don’t know. At least, I hope to retain my youthful spirit and to interest myself in youthful things.”

She paused a moment and went on: “I’ve lived — and the struggle has been worth while. You know, the reason people are so conventional and so unable to budge is because they are tied down by material things. I have found that you can get along with a good deal less than you think necessary and yet maintain health and a degree of comfort.”

On the table of her modest sitting room were half a dozen red roses — beautiful, delicate, fresh buds — on long stems in a bowl. “I’d much rather” — and she gestured lightly towards them — “have roses on my table than diamonds on my neck. A rose is still accessible to me and I don’t want a diamond necklace.” She smiled quickly to emphasize her plain philosophy of living.

“Nothing Else But Liberty”

“Whatever will happen,” she said after a pause, “will happen. I hope to die on deck, true to my ideals, with my eyes towards the east — the rising star.

“Yes, if I had life to live over again, I might avoid some of my mistakes, but in the fundamentals — in the light of the war and of Russia — I am more convinced than ever that nothing else but liberty as the basis of society and of life will ever solve the present problems of the world.”

So much for a glimpse of the mind and philosophy of this stormy petrol of womankind, this avowed anarchist who was admittedly born a rebel and who has always been a rebel against society as it exists, this passionate fighter for liberty, who has always been prepared to tilt with the entrenched forces of coercion as represented by constituted governments. She went to Russia — shipped there by the inflamed and frightened USA — in the hopeful frame of mind of a fundamentalist going to heaven — only to find there a tyranny over the individual worse than that which she had encountered in the United States plutocracy. Her dream of seeing an anarchistic utopia in action shattered, she left Russia of the Cheks in disgust, and has returned once more, at least temporarily, to the western world.

It is hard perhaps to reconcile the Canadian view of Emma Goldman, of this placed, experienced woman of the philosophic outlook and the scholarly mind who apparently finds nothing at the moment so interesting as to give in such of the bourgeoisie as care to attend academic lectures on Ibsen, Tchekov and other dramatic giants, with the idea of the wild woman whom the United States jailed for her incendiary beliefs and finally threw out for her inflammatory teachings. But then it must be remembered that the late Eugene Debs, by all accounts as gentle a soul as ever drew breath, was also kept for years in an American jail because of the menace that his teachings were to society. With Comrade Goldman, as with Comrade Debs, the one an anarchist, the other a Socialist, the impulse to fight for liberty, the instinct to rebel, flamed in the mind, the heart, the spirit. They were not matters of manner or appearance.

It is hard perhaps to reconcile the Canadian view of Emma Goldman, of this placed, experienced woman of the philosophic outlook and the scholarly mind who apparently finds nothing at the moment so interesting as to give in such of the bourgeoisie as care to attend academic lectures on Ibsen, Tchekov and other dramatic giants, with the idea of the wild woman whom the United States jailed for her incendiary beliefs and finally threw out for her inflammatory teachings. But then it must be remembered that the late Eugene Debs, by all accounts as gentle a soul as ever drew breath, was also kept for years in an American jail because of the menace that his teachings were to society. With Comrade Goldman, as with Comrade Debs, the one an anarchist, the other a Socialist, the impulse to fight for liberty, the instinct to rebel, flamed in the mind, the heart, the spirit. They were not matters of manner or appearance.

One wonders how the ordinary person pictures Emma Goldman, the Bolshevik, who made America shudder and shiver. Does not the mention of her name conjure up a wild-eyed woman of streaming hair, disheveled dress, shrieking words, fighting fists — more or less after the fashion of the ladies of the tumbrils and the guillotine in the days of the French revolution? I do not want to do Miss Goldman an injustice, and I have no doubt that in periods of active rebellion she has been able to pour out lava in the finest accepted rebel manner, but I would like to depict her as I found her, a dormant volcano at least, peaceful, picturesque and altogether beneficently fitting into our quiet home atmosphere.

In Her Toronto Home

To find her, I climbed a dark stairway that goes up inconspicuously between two stores on Spadina avenue. At the head of them in the shadows, was a locked door at which I knocked. It was all very mysterious. I felt all of a twitter. Was I not about to enter, alone, the secret haunt of a bomb-hurling, blood-curdling, temple-wrecking enemy of the social order? I knocked again, and again. The door opened at last; and a youngish man, Jewish, invited me up another flight of stairs. He left me on the uppermost landing while he went into a front room from which came the busy clicking of a typewriter. This stopped. A brisk voice clipped out, masculinely: “Ask him to wait for a minute in the other room,” and he ushered me into a plainly furnished bedroom. There he entertained me with the brand of cigaret you would walk a mile for and casual chat about the courtesy which he, a newcomer, had found in Toronto. His talk was anything but Bolshevik, but I found it merely a strained attempt to fill in an awkward interlude, and I was about to make an effort to probe, circuitously, his exact revolutionary status when Emma Goldman appeared briskly at the door — she gives that impression of alert briskness — and introduced him casually with “My brother — Doctor Goldman.” So that was that.

“Take off your coat,” she said as she showed me into the front room — her sitting room, from which opened off her sleeping room. “Sit where you will be most comfortable.”

And we talked with the table between us, with the roses on it and her typewriter, in this modest bed-sitting room up over Spadina avenue which is the Toronto home of this celebrated woman.

“I am not accustomed to this primitive method of heating,” she said once as she bustled over to throw coal on the tall little stove in the middle of the floor which gave the rooms the frontier flavour of a room in the north country. “Sometimes I forget about it and it goes out on me.”

She said this as if she utterly lacked any sense of irritation or complaint — in the same passionless tone exactly which she used later when telling of her harsh treatment at the hands of the American authorities. Yet throughout she gave every evidence of a capacity for intense feeling; and always in her talk there was a delicious undercurrent of humour — but it was as if she had a tremendous restraint, as if her experience and philosophy had long since taught her that life and living, and especially the religion of liberty to which she so passionately adheres, were much bigger than a mere desolated hearth, imprisonment or deportation.

In the narration of her career, she might have been talking to a stranger as she clipped out briskly the bald recital, without comment, without venom, without a single parenthesis or emotion or emphasis, without a word of intolerance or disgust or personal feeling. You knew she felt acutely, you could sense the strain of re-living some of the harsher moments of her career — her voice grew hoarse with the telling and she had to excuse herself to get water — but never was there a lessening of this quiet, almost gentle, control.

Her appearance? You might see Emma Goldman in a crowd or a streetcar and not notice her. She is short and with the full figure of middle-aged women of her race. But her figure gives an impression of firmness and strength; and her movements are quick and energetic. She is light on her feet, as the saying goes; light, one thought, as a girl. Her face, bold, square, strong and strangely spare for a full-fleshed woman, has a masculine rather than a feminine note. It is calm, serene possibly would not be too rich a word, with the serenity that experience brings; unwrinkled, when you consider that here is a woman of fifty-six whose life had not been placid or easy. It is a pioneer face. Possibly the only suggestion of the rebel is in the hair which rises sturdily from the brow and seems to bend back ruggedly against its will cross the head. This hair, just touched with gray, gives quality to the general vitality which the face holds. Alone, it would prevent her from ever appearing commonplace.

It is strange, perhaps, but I came away without a definite remembrance of the eyes that looked through black-rimmed glasses. When she talked, she kept them lowered, not merely in the absorption of remembrance, but as if she wished to keep shuttered the soul that might flare in them when she spoke of tyranny or inhumanity.

“It’s a long story” — and Miss Goldman laughed when I asked her how she became an anarchist. “It began with a very tragic event in my youth — though I always say that rebels are born and not made. I think I’m a born rebel.”

“It’s a long story” — and Miss Goldman laughed when I asked her how she became an anarchist. “It began with a very tragic event in my youth — though I always say that rebels are born and not made. I think I’m a born rebel.”

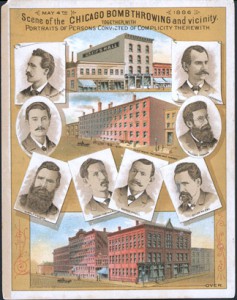

She was sixteen in 1886, when five men were hanged for alleged complicity in am American bomb-throwing incident. Subsequently, when Governor Altgeld after investigation, freed from jail three of their fellow accused who had escaped execution he issued a statement that they had been sacrificed by a packed jury to the clamour of the press, and that the five who had been hanged were innocent, too. At that time she was a young seamstress, dressmaker, in Rochester, where her parents and people lived. The injustice of the whole affair made a deep impression on her, and from that moment she began her study; she began her fight against oppression; she became rich soil for the seeds of anarchism.

In 1889 Emma Goldman went to New York with fifty cents in her pocket and a desire to make a career. None of the successful Babbitts of American life, the poor boys who became steel magnates and oil barons, had a better traditional start than this girl Wittington (?) of nineteen. But she was differently routed for fame. She kept on at dressmaking; and she took an undergraduate course in militant radicalism. At that time there were few rebel stirrings of a native American character. But Emma’s mother was German; German was the first of many tongues she learned to speak and she found in the German and Yiddish labour movements the impetus to the anarchism which she subsequently embraced.

In 1893 she took part in a cloakmakers’ strike, quoted in a speech no less an authority than Cardinal Manning that “necessity knows no law,” was charged with “supposed inciting to riot,” and was given a year’s imprisonment, which she served, on Blackwell’s Island.

Jail Hardened Rebel Instincts

She confesses to gratitude to the American authorities. This year in jail tempered and hardened her rebel instincts, gave them definite direction — and in addition gave her a year of intensive reading in which she acquired the English tongue and an appreciative acquaintance with Emerson, Whitman, Spencer, all the writers whom she regards as men of freedom, spiritual anarchists. She had a university course not merely in rebellion but in literature. From that time dates not merely her real anarchism, but her culture. perhaps it is not too much to say that she would not be today giving Toronto authoritative lectures on the dramatists if she had not had that year’s jail study.

From it she emerged with experience, a hammered-out philosophy and shattered health. She had been anxious to be a nurse and the late Dr. White, jail physician, a great humanitarian, gave her the opportunity to learn the fundamentals. There was a prison hospital ward of sixteen beds. He scoffed a the sentence imposed on such a slip of a girl as Emma was then and he had her transferred to the hospital ward. And there the young anarchist played the part of a jail Florence Nightingale. She got very little sleep. Four or five times a night she had to be up attending to the sick inmates. And as a result her own health gave way.

When she came out she went to Europe, went to Vienna, to study. There she took courses in dietetics and children’s diseases, as well as pursuing her quest for a mastery of the world’s great literature. At that time there was a minor renaissance in Europe, a minor golden age of thought and letters; and Emma Goldman was caught in it and developed by it at first hand. She threw herself into it with all her hunger for liberty and light and she came out of it equipped for the struggle that was to be hers.

In Vienna she sat at the feet of the famous Professor Freud in his original lectures. Her contacts of this intellectual kind are remarkable when you learn that she had an acquaintance that ranged from Freud to Theodore Dreiser, and from Lenin to Sinclair Lewis. Dreiser and Sinclair in their youthful formative days were by way of being disciples of hers when she was running a magazine later in New York.

Returning to the United States, she toured the country in 1897 from New York to Santiago, lecturing on all sorts of subjects — this woman who had arrived in new York not ten years previously immature and virtually unable to speak English. This first of her cross-country tours made her an American national figure, not because of her lectures but because of the persecution of her by the police who stopped her meetings and frequently arrested her. It drew to her side hundreds of sympathizers. Indeed it may be seen how surely the United States themselves forged the famous woman who is today Emma Goldman, anarchist and outlaw.

Then came the assassination of President McKinley in Buffalo. And again she owes a lot to American injustice — especially to the injustice of the Hearts press. The Hearts papers shrieked to the inflamed American people that Emma Goldman had inspired the young man who shot McKinley. As a matter of fact it is pretty general historic knowledge that the Heart papers had carried on such a campaign against McKinley that there were people not above accusing them with being the inspiration of McKinley’s murder. But the Hearst papers centred on Emma Goldman as the cause.

“As a matter of fact” — and Miss Goldman said this with a calm inconsequence that chilled one like the touch of death — “if I had been in New York at the time, I would not have been alive today. There is little doubt that I would have been sacrificed.”

$20,000 Reward for Her

Emma Goldman had nothing to do with the death of McKinley. Before the assassin went to the electric chair, he assured the warden that she had had absolutely nothing to do with his act. And yet a reward of $20,000 was offered if she culd be got into the state of New York.

She was in St. Louis at the time and immediately took the train to Chicago, where she was arrested. Her subsequent release came about not so much because of her innocence which a third degree grilling from ten in the morning to midnight could not shake but because of petty internal politics in the Chicago police force which is too long a story to detail. But she was freed to spite certain parties involved in a local quarrel.

The panic over, she returned to New York city in November, 1901. But every door was closed against her; she could not even use her name. Temporarily she took the disarming name of Smith, E. G. Smith; she lived in an east side tenement and she nursed for the east side doctors.

After the McKinley affair, she went abroad. Returning, she began publishing the Radical Literary Review. It was as editor of this that she met such ardent young literati as Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Edgar Lee Masters and others. Her office was a sort of forum for the radical-minded. In 1910 she published her first book, Anarchism and Other Essays; in 1914 she published The Social Significance of the Modern Drama. She lectured all over the country.

Then came the war. All her life she had been opposed to war — it was part of her fundamental philosophy. She had fought against it, written against it; so when the great war came, she dropped everything else and threw herself with all her vigour into anti-war agitation.

Now there is a queer streak of ironic humour in America’s subsequent treatment of her. But this anti-war talk of hers was not at all unpopular in the country whose popular slogan was “I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier” — the country which re-elected Wilson on the cry, “He kept us out of war.”

When the United States belatedly entered the war in 1917, well! to quote Emma Goldman’s words ‘’ — “They stopped talking against the war. I didn’t.” And, for almost the only time in our chat, she smiled.

It was not that her talk was unpopular with the great American multitude. She concentrated against conscription after America’s declaration of war and on May 9, 1917, she began her own campaign. Enormous crowds came to hear — she had one audience of 50,000 in New York city — and to cheer. And then on June 5th, coincident with national registration, her magazine came out with a cartoon, with a thick black border . . . dedicated . . . “in memory of democracy.”

The United States authorities stopped her magazine, raided her office and seized books and the writings of years which she has never recovered. But all the time she was lecturing with flaming words all up and down the country.

How She Was Deported

She was arrested, of course, tried on a charge of conspiracy to defeat the operations of the government, fought her own case without counsel and was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment and deportation.

Now Emma Goldman was an American citizen, for her first marriage had been to a naturalized American citizen. But she related that the American authorities went to Rochester, found the aged immigrant parents of her first husband and terrorized them into saying that the naturalization that he had taken out forty years previously had not been in order — that he had not been five years in the country when he made his declaration, and was not even twenty-one. So that he was never really naturalized. And, ergo — Q. E. D. — neither was his wife!

Therefore, further, she could be quite legitimately deported when the time came.

Now when Emma Goldman finished her twenty-one months in a Missouri jail she might have, if she had adopted a Brer Rabbit strategy and lain low, escaped deportation. But it was not in her gospel to lie low. Out on $25,000 bail pending deportation, she toured the country lecturing: and on December 10th, 1919, more than a year after the war was over, but at a time that the United States were shuddering over Bolshevist shadows at every corner and filling the jails with every possible suspect from Debs downward — she received a wire in Chicago to report to Ellis Island for deportation. She caught the Twentieth Century Limited and drove from the station to the immigration pens. Here she was held.

At four o’clock on the morning of December 21st, a dark, drear, chill winter’s morning, she was awakened out of sleep and told to dress. And she and 248 other politicals, scores of them working men still in their working clothes, many of them men who had been arrested at their jobs and whisked off for deportation, without their families knowing whether they had disappeared, were led out on board a tender — passing between massed lines of soldiers, immigration officers and officials of the departments of Labour and justice, a regular embattled army of guards. The entire paraphernalia of America’s might had been mustered to see that Emma was safely put on board the Buford, a miserable ship of Spanish-American war antiquity. On board were seventy soldiers to see that she and the others did not mutiny.

The captain sailed with sealed orders and cruised all over the Atlantic for twenty-eight days, finally ending up in Finnish waters where, by agreement with Finland, Emma Goldman and the others were landed en route to Russia.

Which brings her pilgrimage to date. For her Russian adventure is known. She did not find there the land of liberty of which she had had anarchistic dreams. But that has been told. Enough that she is here in Toronto, a woman of remarkable experience . . . . It seems pretty safe to prophesy that . . . (hard to read) her experience in Russia was not enough to extinguish the flame that is in her heart. ♦