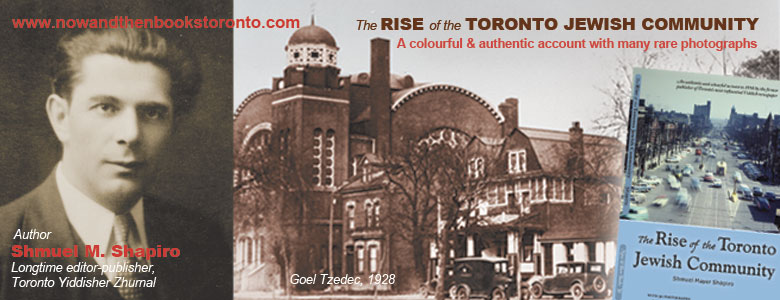

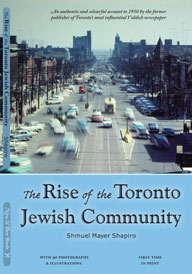

The following passages have been excerpted from The Rise of the Toronto Jewish Community, by Shmuel Mayer Shapiro (1877-1958), the late editor and publisher of the Toronto Yiddish newspaper, the Hebrew Journal. After surfacing in a synagogue archives in 2009, his unpublished manuscript was illustrated with some 90 rare and historic photographs and illustrations and published in 2010 by Now and Then Books. (www.nowandthenbookstoronto.com) It is now also available from Amazon.com as a Kindle e-book. Click here to purchase book from this website.

The following passages have been excerpted from The Rise of the Toronto Jewish Community, by Shmuel Mayer Shapiro (1877-1958), the late editor and publisher of the Toronto Yiddish newspaper, the Hebrew Journal. After surfacing in a synagogue archives in 2009, his unpublished manuscript was illustrated with some 90 rare and historic photographs and illustrations and published in 2010 by Now and Then Books. (www.nowandthenbookstoronto.com) It is now also available from Amazon.com as a Kindle e-book. Click here to purchase book from this website.

In these sections, Shapiro describes Toronto in the period before the First World War, a time when the city was receiving thousands of Jewish immigrants each year and the need to assist them was great. He also describes the various Christian missionaries that used to operate in the old downtown “Ward” neighbourhood.

* * *

Talking Politics

In the first decade of the present century, from 1900 to 1910, the Jewish population of Toronto showed very little interest in politics. The city of Toronto, like the rest of the province, was solidly Conservative. Despite some opposition from the Liberals, the Conservative candidates were always elected to office with overwhelming majorities. There was no socialist party to vote for and the workers seldom put forward a candidate of their own. The more well-to-do Jews, the assimilated Yehudim, and the parvenu rich invariably backed the Conservatives.

Sometimes, when an issue affecting the interest of the local Jewish population as a whole would arise, a few of these individuals would step forward, unbidden, as representatives of the community. In time these self-appointed Jewish leaders became the recognized intermediaries between the civic administration and the Jewish community. They were befriended by politicians seeking office and utilized as vote getters. In return for political favours these so-called leaders of the community would promise to get the Jewish vote for their candidate. On his side the candidate, in his campaign speeches, would promise to defend the interests of his Jewish constituents if elected to office.

Sometimes, when an issue affecting the interest of the local Jewish population as a whole would arise, a few of these individuals would step forward, unbidden, as representatives of the community. In time these self-appointed Jewish leaders became the recognized intermediaries between the civic administration and the Jewish community. They were befriended by politicians seeking office and utilized as vote getters. In return for political favours these so-called leaders of the community would promise to get the Jewish vote for their candidate. On his side the candidate, in his campaign speeches, would promise to defend the interests of his Jewish constituents if elected to office.

Apart from these professional Jews, however, few other Jews took an active interest in politics, whether municipal, provincial or national. They saw little real difference between the two parties or their candidates. One was as good or as bad as the other and in any case, they felt that both parties represented the same interests. Furthermore, the immigrant couldn’t understand the English speeches of the rival candidates, the issues were obscure to him, and there was no Jewish candidate running who could appeal to this national pride. In the eyes of the immigrant all parties were alike in that they took very little interest in the affairs of the working man.

The centre of the immigrants’ political activity, forty and fifty years ago, was to be found in the numerous ice-cream parlours and Jewish soft drink pubs that had sprung up, like mushrooms after a rain, all through the Jewish district. As soon as the immigrant managed to accumulate a few dollars he would invest his saving in an ice-cream parlour. The sale of ice cream was actually only a very small fraction of the storekeepers’ business. Here it was possible to get a meat sandwich or a hot cup of tea, a package of cigarettes or a glass of siphon water, the popular drink at the time (today’s bottled drinks were still unknown).

In the back of the store were a few small tables where the customers could sit down and order a meal. However, most of the time the regular customers just sat and talked, or read the newspapers, or played a game of dominos or cards. The discussions were always lively and often stormy, with everyone in the store taking part. Jewish problems were carefully analysed; political affairs were discussed noisily with no pretense of objectivity. Tempers often flared and it was not uncommon to have an argument end in a brawl. Young suitors courted their belles under the benevolent eyes of the storekeeper and his customers. Not a few happy marriages had their beginnings in these ice-cream parlours.

A few of these places were frequented exclusively by the local Jewish intelligentsia. After work, intellectuals of every type, Zionists and socialists, genossen and chaverim (beneficiaries and comrades) would drop in for a cup of tea or a game of chess, often staying long into the night, talking and arguing, with everyone trying to prove the superiority of his group or ideology.

One of the most popular places stood at the corner of Louisa and Elizabeth Streets, in the very heart of the then Jewish neighbourhood. It was owned by several partners, Mr. Shimon Colofsky and the two brothers Messrs. Samuel and Joseph Rosenfeld. There are good grounds for believing that their chief reason for opening the store was to provide a social centre for immigrant intellectuals. Themselves workers — the two Rosenfelds made a comfortable living as carpenters and Mr. Colofsky ran a small business with some success — the owners were eager to promote the intellectual life of the young community. When their day’s work was done, these gentlemen liked to repair to their store, wait on the customers, and listen to the various discussions going on. Some evenings the customers were entertained with more formal discussions, readings from the Yiddish classics and talks on Zionism, territorialism and other subjects of special Jewish interest.

But literature and politics were not the sole interest of the habitués. Chess was very popular and tournaments were held frequently. One of the most interesting players was a Mr. I. Rosen, a bookkeeper by trade. He was always the first to come and the last to leave, and was looked up to as a great authority on all matters relating to chess. He spent all his time at the chessboard, only occasionally absenting himself to take some little job that he couldn’t very well refuse.

Another such store, belonging to Messrs. Chanan and Boris Dworkin, was located at the corner of Albert and Chestnut Streets. It was later moved to 64 Elizabeth Street. The proprietors extended credit to their regular customers and their generosity soon brought them a larger trade. The customers coming here were, generally speaking, bitter opponents of Jewish nationalism, being mainly Bundists, anarchists and other anti-Zionists.

A third store, located at 102 Agnes (today’s Dundas) Street was owned by Mr. Yitzhak Herman, a native of Wolin. The store was a favourite rendezvous for Poalei Zionists, Talmudic students who liked a game of chess, and various young men starved for the life of the mind. Passing for an intellectual, Mr. Herman was in reality a rather naïve person. Watching the customers queuing up to his counter for cigarettes and tobacco, he decided that the retail tobacco business had a great future. When he learnt further that the Imperial Tobacco Company made huge profits buying tobacco and making their own cigarettes, he decided that there was no earthly reason why he couldn’t do the same thing. He began to package and sell his own tobacco a few cents cheaper per package and watched with elation as sales rose briskly. He soon became inebriated with visions of getting rich quick.

Unfortunately, a week after he launched his scheme he was visited by revenue officers from the Excise and Revenue branch of the Dominion government. Mr. Herman now discovered to his dismay that the violation of patent rights was a serious matter and the evasion of excise duties even more so. Mr. Herman had a hard time convincing the authorities of the innocence of his scheme. The legal suit cost him a tidy sum but he was lucky to escape with his whole skin. Previous to this incident, he had worked in a local shoe factory; now he was forced to return to his old job and leave the management of the store to his wife.

A fourth ice cream parlour was opened at the corner of Armoury and Chestnut Streets by a Mr. Greisman. Most of Mr. Greisman’s customers were Galician Jews who had come from the part of Poland annexed from Austria after the First World War.

Another ice cream parlour, Michaelson’s at 97 Agnes Street, became the headquarters of Roumanian Jews and the meeting place of young men and women with a passion for the theatre. Having acted on the stage in the old country, Mr. Michaelson, the owner of the store, never stopped talking of his past theatrical glories. He was always nostalgically reminiscing of the good old days when his appearance on the boards was the signal for tremendous applause.

Vanity apart, however, Mr. Michaelson’s interest in the theatre was sincere. He was in fact the first in Toronto to produce a Yiddish play. In 1904 he organized an amateur theatrical group with himself as director. And a year later, in 1905, he was instrumental along with Mr. Abramov in bringing to Toronto a cast of professional actors from New York, thereby laying the groundwork for the legitimate Jewish theatre which later arose in the city. The company gave a series of performances of famous Yiddish classics in a hall that Michaelson rented for the occasion. But interest on the part of the community was lukewarm and the group had to disband after a few months.

Vanity apart, however, Mr. Michaelson’s interest in the theatre was sincere. He was in fact the first in Toronto to produce a Yiddish play. In 1904 he organized an amateur theatrical group with himself as director. And a year later, in 1905, he was instrumental along with Mr. Abramov in bringing to Toronto a cast of professional actors from New York, thereby laying the groundwork for the legitimate Jewish theatre which later arose in the city. The company gave a series of performances of famous Yiddish classics in a hall that Michaelson rented for the occasion. But interest on the part of the community was lukewarm and the group had to disband after a few months.

Two of Toronto’s first Jewish restaurants opened in 1900 or slightly thereafter. One, at 119 Elizabeth Street, was run by Mrs. Tucker; the other, on Teraulay Street, was managed by Mr. M. Goldenberg. These restaurants had their regular customers who used to stay on after meals to talk with friends. But these restaurants never equaled in popularity the less pretentious ice cream parlours as centres for social gatherings. In fact, apart from the few synagogues and a small socialist club on Queen Street, there was no Jewish centre at all for people to meet and spend an evening together in a friendly atmosphere. The situation didn’t improve until two Toronto Jews — Mr. S. Fleishman, a local musician, and Mr. David Sussman, one of the founders of the Ostrovtzer Synagogue — realizing the needs of the growing Jewish population of the city, opened the Center Palace Hall on Elm Street.

Assisting the new arrivals

In the early years of the century, the small Jewish community of Toronto had many serious problems to cope with. The most pressing one was, of course, how to absorb the large number of immigrants that were steadily arriving. The housing situation in the city was serious. Accommodation for the newcomers had to be found at once, and food, and clothes. The vast majority of the arrivals were wretchedly poor, with their worldly possessions literally on their backs, in the form of heavy bundles strapped onto their bodies. Their tattered suitcases bulged with hand-sewn pillowcases, feather-filled bedding, heavy woolen underclothes, and the traditional pair of silver candlesticks. They had no money to speak of. Their clothes were old and worn, their bellies empty, their spirits low.

There was then no Canadian Jewish Congress or Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society to turn to. These and similar organizations did not arise until later. In those days the small Jewish community in Toronto had no organizations to look after the needs of the immigrant. There were no experienced social workers to meet the immigrant as he came off the boat, to provide him with a lodging however temporary, and to advise him on the choice of an occupation. The immigrant then had to rely on his own resources, initiative and enterprise.

Nevertheless, the newcomers did receive some assistance, however small, from the generation of immigrants before them. This help was largely private and voluntary. And it did not come from the rich who, generally speaking, held themselves aloof from the Yiddish-speaking masses.

Shocked by the general apathy towards the plight of the new arrivals, a number of the more humanitarian members of the community decided to do something. They personally began canvassing for funds, knocking at doors of private houses and asking for donations of money, clothes or medicines. They would then hand over the money or articles of clothing to the most needy cases — sometimes keeping a family from starvation, sometimes saving a sick child, sometimes helping an expectant mother with medical care she couldn’t herself afford. This help was sometimes considerable and was deeply appreciated by the newcomers. A few unscrupulous persons sometimes took advantage of the wave of public sympathy for the suffering immigrants and exploited this sympathy for their own profit: callously they appropriated the moneys they collected.

More organized attempts were also made to collect relief to alleviate the widespread poverty within the Jewish population. Although such efforts met with only slight success, they were nevertheless the first organized activities in the young community. A single instance will suffice. A small dispensary was opened at 218 Simcoe Street and free medicine distributed to the needy. In the same three-storey house there was also an orphanage, taking up two rooms. One of these rooms was used as a cheder, where the children were given an elementary Jewish education; the other was reserved for the staff, which consisted of one supervisor.

The house had originally been rented at $25 a month and was eventually bought for $11,000. When, six months after the building was purchased, the first payment fell due — the amount was exactly $50 — there wasn’t enough money on hand. Fortunately, an employee of the Chestnut Street branch of the Crown Bank, Mr. Joseph Gurofsky, offered to provide the money if he were given a promissory note signed by several respectable men. Ten persons came forward to endorse the note, each guaranteeing to pay $5 if it was not redeemed. Mr. Gurofsky then gave the money and the interest on the house was paid. When the note was finally redeemed it was given to Mr. S. Frimes, a local jeweller, in whose keeping it has since remained.

The Christian Missionaries

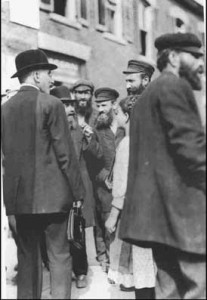

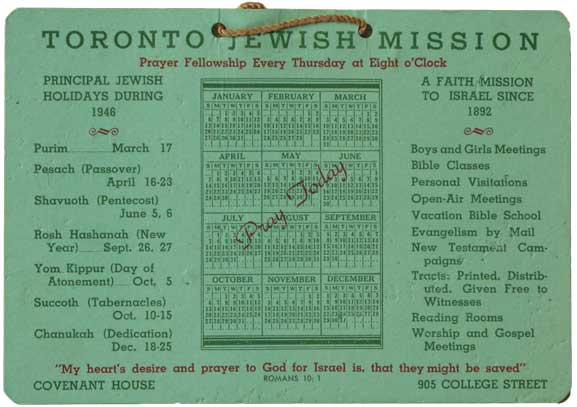

Again, there were those who tried to profit from the misery of the immigrants; this time, however, there was no attempt to fleece the public and the motives were spiritual, not financial. We are of course referring to the missionary societies, whose purpose was to save souls — Jewish souls. And particularly those of the unhappy immigrants who could at times barely manage to keep body and soul together. These missionary groups were quick to take note of the often desperate plight of the newcomers and proceeded to intensify their work among the Yiddish-speaking masses. Converted Jews, able to speak Yiddish, were sent out to preach the gospel of Christ to their erring brethren and to bring the “light” to them. Of course, material help was offered too. Mission houses and hostels, where hungry and homeless newcomers could get a meal or a night’s lodging, were built in the Jewish district. And the missionaries at the beginning had, it must be admitted, some success. Many an immigrant, hungry and without a roof over his head, was forced sometimes to take advantage of their material offers. There were no Jewish institutions at the time to care for the hungry and the unemployed.

The first of the Jewish missionaries in Toronto was Mr. Henry (Nachum) Singer. He had come here from Leeds, England, and was placed in charge of a mission on Centre Avenue, in the heart of the Jewish quarter. He had two female assistants, both very devout Christians. Singer himself was no scholar and his speech was a mixture of German and Yiddish. He stood over six feet tall and possessed a powerful physique, a very impressive figure indeed. His voice was deep and magnetic and when he preached in the street he could easily be heard a block or two away.

The first of the Jewish missionaries in Toronto was Mr. Henry (Nachum) Singer. He had come here from Leeds, England, and was placed in charge of a mission on Centre Avenue, in the heart of the Jewish quarter. He had two female assistants, both very devout Christians. Singer himself was no scholar and his speech was a mixture of German and Yiddish. He stood over six feet tall and possessed a powerful physique, a very impressive figure indeed. His voice was deep and magnetic and when he preached in the street he could easily be heard a block or two away.

Every morning a few Jews, hungry and out of work, would turn up at his mission. After the services, which consisted of short prayers and some hymn singing, they would be served coffee and bread. Then Mr. Singer would set out, accompanied by his visitors of the day, on a round of visits to the local factories to try to find them work. And often he was quite successful, managing to find jobs for at least a few of them. The others, still without work, would return with Mr. Singer to the mission where they would again be served bread and coffee, sweetened by a sermon on brotherly love.

On almost any summer evening one could find Mr. Singer standing on some street corner in the Jewish quarter surrounded by members of his mission and preaching to the Jewish passersby. After the group hymn-singing that was customary on such occasions, Mr. Singer would step forward to deliver his familiar exhortation. In no time at all a large crowd — and usually a few hecklers — would gather round him and listen smilingly to his florid oratory. It was his habit to introduce his sermon with a Hebrew text from the Old Testament. He would begin in a low voice, point out the divine authority of the particular verse he had chosen, then try to prove that the Jewish prophets had foretold the advent of the Christ. Full of deep emotion, his voice would slowly rise in volume, until at the climax of his sermon it would be reverberating all through the neighbourhood. The sermon finished, Mr. Singer would invite his listeners to accompany him to the mission, there to enjoy a light repast.

As far as is known Mr. Singer made only three converts during his long ministry in Toronto and in the eyes of the Jewish community these did not represent a great loss. The first of the converts was a local cloak operator, Mr. Sam Brown by name, who had been born in Bialystok and had lived in Leeds, England, before coming to Canada. His reputation in the community was not very high and it was alleged that he spent most of his time loafing on street corners. The second was a somewhat “queer” individual, Mr. Hershel Solomon, about whose origin nothing was known.

The third of Mr. Singer’s converts was Mr. Yankel Braverman, who had come here from Zhitomir, Poland, where he had left behind a wife and children. It was believed Mr. Braverman changed his faith in order to marry a Gentile woman that he had fallen in love with. All in all Mr. Singer was not able to make much capital out of his successes in the Jewish community. Despite police protection — there were always two constables present at these meetings to keep order — none of the converts dared to preach or take part in public hymn singing in their old neighbourhood.

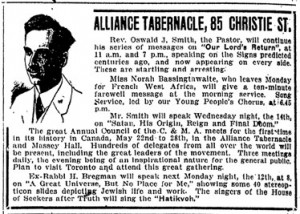

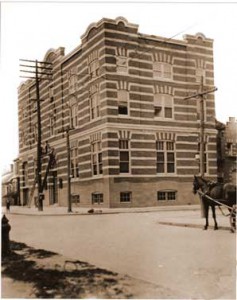

Another mission house, much larger than the first — it occupied a new three-storey building — was located at 257 Elizabeth Street, at the corner of Elm. It was headed by the Rev. Sabati B. Rohold, a converted Jew born in Jerusalem. As a young man Rev. Rohold had gone to England to study. He had been converted there to Christianity and had entered a Protestant theological seminary, eventually graduating as a minister.

Another mission house, much larger than the first — it occupied a new three-storey building — was located at 257 Elizabeth Street, at the corner of Elm. It was headed by the Rev. Sabati B. Rohold, a converted Jew born in Jerusalem. As a young man Rev. Rohold had gone to England to study. He had been converted there to Christianity and had entered a Protestant theological seminary, eventually graduating as a minister.

At the mission house on Elizabeth Street Rev. Rohold was in charge, with Mr. Singer and Mr. Henry Bregman under him. When a Jewish convert was to be baptized, Rev. Rohold would always personally officiate at the ceremony. He was a man of wide learning, familiar with the Talmud and other Jewish religious works. Quite often he would challenge one of the Toronto Orthodox rabbis to meet him in a public debate. Needless to say, his humiliating challenges were never taken up. Knowing from experience the futility of debating over religion, and regarding it as beneath their dignity to accept, the rabbis ignored his challenges. All in all the worthy reverend made very little headway among the Toronto Jews.

Mr. Bregman, a third Jewish missionary to preach in Toronto, was born in Homel, Russia. Before coming to Canada he had lived for some time in England, where he was converted. Mr. Bregman had had a rigorously religious upbringing and in his youth had married the daughter of an Orthodox rabbi. Indeed, for a short time he had preached in the Northampton and Vine Court synagogues in London, substituting for the Skidler Maggid, the regular preacher.

We learnt something of Mr. Bregman’s history from Mr. Joshua Singer, one of the oldest members of the staff of the Toronto Hebrew Journal. Mr. Singer had been a writer for the Jewish Express, a Yiddish weekly published in London, England at the turn of the century, and in the course of his duties had got to know Mr. Bregman quite well. When he met him again years later in Toronto, Mr. Singer was astonished to learn that Mr. Bregman had become a missionary. When he demanded an explanation, Mr. Bregman confided that he had tried in vain to obtain a divorce from his wife, a singularly ugly woman, and that because he couldn’t bear to live with her any longer, he had out of spite and in order to force her to part from him, turned to Christianity, in which in the end he perhaps found a sincere consolation.

The missions were of course more interest in the immigrants’ spiritual salvation than in their material welfare, but converts were more easily made when material assistance was given. The Jewish apostates considered the immigrants very fair game; conditions were favourable. The country was passing through a severe crisis: unemployment was widespread, jobs hard to get. Many newcomers experienced actual hunger, frequently not knowing where the next meal was coming from. There were no Jewish organizations to turn to for assistance.

In their despair, some of the immigrants came for help to the missionaries. A free meal was always available; occasionally a job. Indeed, in the eyes of some, the missionaries were not an unmitigated evil. After all, they helped materially and it was believed that few Jews would actually be lured from their faith. Some of the Gentile manufacturers were more apt to take on Jewish workers if they were recommended by the missionaries. Generally speaking, the Jewish population could do very little for the unemployed. Only Rabbi Solomon Jacobs, then at the head of the Holy Blossom Synagogue, took an active interest in their plight and tried to help. As a rule, however, the unemployed immigrant had to shift for himself. ♦

Excerpted from The Rise of the Toronto Jewish Community, by Shmuel Mayer Shapiro. Originally written about 1940 and published for the first time from an original manuscript by Now and Then Books in 2010. Please visit the website www.nowandthenbookstoronto.com for purchasing information.

See also Cynthia Gasner’s story, Pre-1950 Jewish Toronto manuscript published.