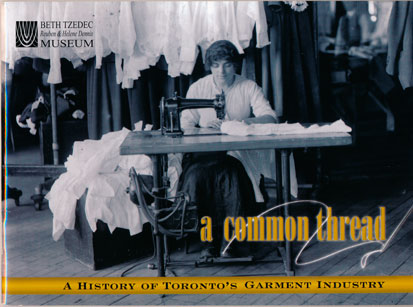

Through a series of colourful panels, photographs, display cases, clothing racks, and stand-alone artifacts such as a 1917 Singer treadle industrial sewing machine, the exhibition, A Common Thread, which opened recently in the Reuben and Helene Dennis Museum of Beth Tzedec Synagogue, offers a lively and compelling look at the history of Toronto’s garment industry from the early 1900s to the present.

Through a series of colourful panels, photographs, display cases, clothing racks, and stand-alone artifacts such as a 1917 Singer treadle industrial sewing machine, the exhibition, A Common Thread, which opened recently in the Reuben and Helene Dennis Museum of Beth Tzedec Synagogue, offers a lively and compelling look at the history of Toronto’s garment industry from the early 1900s to the present.

Although the subject is vast, it fits the museum like a glove because of the Jewish community’s integral involvement in the shmata trade from the days when it dominated Spadina Avenue. to more recent times when it often seemed to dominate the financial pages as well.

By highlighting many intriguing details, the exhibition manages to capture many facets of an enormous story in a relatively small space.

A century ago, thousands of unskilled Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe had begun to pour into what was then a predominantly Anglo-Scottish city. Taking up residence in the cramped, impoverished “Ward” neighbourhood, many found work sewing for the T. Eaton Co., Simpson’s and other large firms.

Some did piecework in local sweatshops, which were never as bad as their notorious counterparts in New York. Decades later, Holocaust survivors and other immigrants continued to find their first crucial jobs within the massive industry that still dominated the Spadina-Adelaide area of the city.

In many ways the garment trade spurred the growth of a downtown Jewish neighbourhood. Many Jewish shops, restaurants and synagogues appeared in the Spadina area, as did large factory buildings

and landmarks such as Kensington Market.

Only in the ’60s and ’70s, when downtown rents began to skyrocket, did the fashion industry begin to move into the suburbs, and the neighbourhood entered a decline.

A central theme of A Common Thread is the labour movement. Throughout the century, workers struggled continuously for better working conditions, shorter work weeks, better wages, better job

security, and more inclusive health plans. “We want a 1912 living standard!” read one worker’s banner during a 1912 strike at Eaton’s.

After learning the tricks of the trade, many Jewish workers left the large firms and established small tailoring shops of their own. Such operations were a mainstay of main streets from Kapuskasing to

Kingston. With equal measures of work and luck, a few of these enterprises grew into large businesses, often with reputable labels that are still recognizable today.

Formerly employed at Eaton’s, Abraham Posluns and son Joseph started manufacturing clothing in a tiny garage in 1914, and soon began filling orders for Eaton’s and others. Half a century later, their

descendants, the brothers Posluns, founded a vast clothing empire that would include such multimillion-dollar brands as Thrifty’s, Harry Rosen, Tip Top Tailors, Fairweather and Club Monaco.

Though mainstay Dylex went bankrupt, other Posluns corporate entities still thrive.

Esther Liebgott – whose maiden name, Nainudel, translates as sewing needle – designed and custom-tailored shapely undergarments so adeptly that she never lacked for clients.

“She supported her family for 40 years with her home sewing business,” exhibition curator Dorion Liebgott recalled of her mother-in-law, one of numerous operators spotlighted in the show who became

minor legends in the community.

A Common Thread reminisces over many such tales of clever industriousness. Specializing in top-quality gowns for brides, bridesmaid and others in the wedding party, the Paloma Blanca by Blue Bird

label has reversed a predominant industry trend by exporting its wares all over the world. The exhibition also celebrates the sparkling sartorial talents of dress designers like Rae Hildebrandt and

Maggie Reeves.

Part of a display on the fur industry, Jewish fur trapper Jack Leve used to traipse through the wilds of northern Ontario, but “never without his canoe, snowshoes, knife, and some kosher salami,” a caption explains.

Like a huge walk-in closet, the exhibition also features colourful references to varied other aspects of the industry from shoes to hats.

According to Liebgott, who spent three years in researching and planning, the exhibition couldn’t have been done on a small budget. She attained a $75,000 grant from the Ontario Trillium Foundation as well as funding from many other supporters.

“I knew that we had to do an exhibit on the garment industry but I didn’t know what I was taking on at the time,” she said. “It’s such a huge story, and as large as I thought it was, it was even larger.”

The exhibition continues through next June. Admission is free; a souvenir booklet costs $20. ♦

© 2003