Toronto city councilors are set to debate a recommendation this week from the City Hall heritage department to designate the former Standard Theatre at Dundas and Spadina — a once-thriving Yiddish theatre that later became the Victory movie house and burlesque palace — as a heritage site worthy of limited protection.

Since its last incarnation as a Chinese movie theatre, the building has been idle for years and its current owners now seek to convert its interior into office space. Although it main-floor auditorium is now a bank, its once-resplendent, art deco-ish upper balcony has been preserved, although in a condition of terrible neglect.

The exterior and the second-floor interior may be preserved if the site is designated, according to Adam Vaughan, the councilor championing the designation, who added that the owners may install a “photo museum” of historic material on the second floor.

“It was grand theatre, but only half remains,” Vaughan said.

A heritage designation would require that any alterations “be done in a sensitive manner that would retain the most important features” of the site, said Brian Gallaugher, the city’s outgoing heritage planning coordinator.

“It can be converted but in a way that respects the original function of the room, so that people would be able to recognize it was once a theatre,” Gallaugher said.

Many notables from the Jewish community and city hall attended the Standard’s opening in 1922, an occasion graced by a bevy of Yiddish performers, singers and an orchestra. In exchange for the promise of discounted theatre tickets, many of the patrons who filled the 1,500-seat auditorium had assisted in the building’s construction by buying bricks for $5 each.

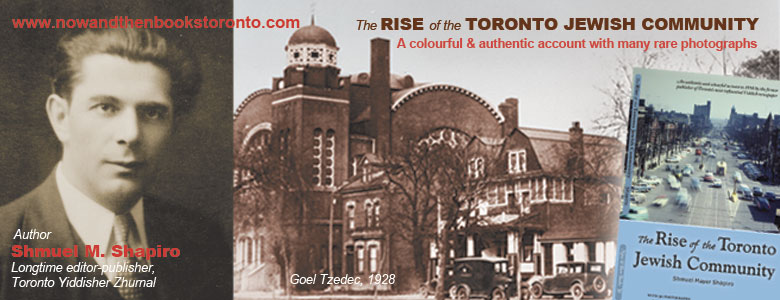

Its architect was Benjamin Brown, whose other notable works include office towers on Spadina and the former Beth Jacob synagogue on Henry Street, now a Greek Orthodox church.

According to historian Stephen Speisman in The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937, the Standard was the first purpose-built Yiddish theatre in Canada. With probably only a dash of hyperbole, historian Hye Bossin called it “the finest Yiddish playhouse in North America and probably the world.”

Maurice Schwartz, Molly Picon, Jacob Ben-Ami and the Adlers and Thomashefskies were among the great actors and acting families who trod its boards in such dramas as Jew Suss, Yoshe Kalb, Sabbatai Zvi, The Brothers Ashkenazi and God, Man and the Devil.

Besides these serious “art” productions, touring companies also brought in plenty of “shund,” less aspiring material that more readily appealed to the masses. “They were usually tear-jerking melodramas,” said Sol Littman, a former Toronto resident (born 1920) who now lives in Tucson, Arizona.

“Usually the plots would involve a son returning home after being a bad boy, or a daughter threatening to marry a Gentile boy, or a husband who marries a second wife in America and then discovers his first wife is alive and is coming to visit,” he said.

“Locally, week by week, there were repertoire groups here in Toronto, and we used to bump into them on Spadina Avenue with their make-up on.” Actors and theatre patrons often hung out in Caplan’s and other lively cafes in and around Spadina.

In the early 1930s, as the children of Jewish immigrants reached adulthood as fluent speakers of English, they turned towards the English stage, preferring, for example, Gilbert and Sullivan to a Yiddish Hamlet or King Lear. The rise of the “talkies” was another factor behind the Yiddish theatre’s irreversible decline.

In the early 1930s, as the children of Jewish immigrants reached adulthood as fluent speakers of English, they turned towards the English stage, preferring, for example, Gilbert and Sullivan to a Yiddish Hamlet or King Lear. The rise of the “talkies” was another factor behind the Yiddish theatre’s irreversible decline.

“The live theatre ended largely because the audience ended,” Littman said.

While Yiddish plays were still imported sporadically into Toronto, the Standard was converted into a movie theatre called the Strand about 1935. It was renamed the Victory about 1942 and was still used for various Jewish cultural events, benefits and political rallies into the 1950s. Later, as the Victory Burlesque, it descended into striptease.

Many Toronto Jews of vintage years still fondly recall attending cultural events at the Standard, or going to movies during the Depression era and paying 10 cents for a fancy dinner plate.

“I not only remember going there, I remember appearing there on the stage,” said Shirley Kumove, a Toronto Yiddish translator. “The Yiddish schools held concerts there. I sang in some concerts and delivered flowers to speakers.”

Then a pupil of the Borochov school on College Street, Kumove even had lines to deliver in one production. “I had to come out on stage and say, ‘Daddy, Daddy, Mommy’s run off!’” she recalled. “To this day, I don’t know whom she ran off with, whether she ever came back, or even the name of the play. I don’t have a clue. I wish I could find out.” ♦

© 2007