Rising from a knoll deep in a Hessian forest, Schloss Sababurg is ringed by a distinctive old hedge of brambles, through which the Grimm Brothers were forced, nearly two centuries ago, to cut a path in order to reach the castle, which was then a noble ruin. (The castle dates from the 14th, the brambles from the 16th century.)

Rising from a knoll deep in a Hessian forest, Schloss Sababurg is ringed by a distinctive old hedge of brambles, through which the Grimm Brothers were forced, nearly two centuries ago, to cut a path in order to reach the castle, which was then a noble ruin. (The castle dates from the 14th, the brambles from the 16th century.)

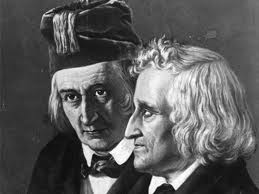

Collectors of fairy tales and legends, the Grimms were quick to identify the castle with Sleeping Beauty — the fairy-tale princess who, having fallen under an evil spell, sleeps for 100 years in a castle that also sleeps, only to be awakened by a kiss from a prince who has hacked his way through the foreboding thickets.

Today, half of Sababurg is still an eerie ruin ringed by brambles, its vast sward a nature park in which aurochs, bison, elks and wild horses wander. Newly awakened, the castle’s other half has been converted into a deluxe honeymoon hotel set in a romantic stone tower. Much in demand, its eight rooms are decorated with antique spinning wheels, tapestries, four-poster beds and plush rugs. (Daytime visitors may have coffee and cake, or a full meal in the hotel restaurant.)

Some 30 km to the south, the Grimm Brothers Museum in Kassel illustrates the immense influence of Jacob and Wilhelm on world literature; the fairy-tales they gathered from simple peasants have been traced back to Eastern Europe, India, Persia and the Middle East. The Grimms also pioneered an early German dictionary and thus influenced the shape of the language itself.

Some 30 km to the south, the Grimm Brothers Museum in Kassel illustrates the immense influence of Jacob and Wilhelm on world literature; the fairy-tales they gathered from simple peasants have been traced back to Eastern Europe, India, Persia and the Middle East. The Grimms also pioneered an early German dictionary and thus influenced the shape of the language itself.

Towns on Germany’s so-called Fairy-Tale Road, such as Gottingen, Alsfeld and Marburg, have enshrined the Grimms in historic sites, statuary and plaques. Along this or any other route in Germany, readers of this column may find many other points of interest, some inevitably pertaining to Judaic themes.

While strolling past the many half-timbered houses and medieval structures of Gottingen’s picturesque downtown, for example, my eye was drawn to an ordinary street-sign: Judengasse, the street of the Jews. Several blocks along this nondescript boulevard, which seems to tell nothing of its past, the town museum beckoned. Three marks gave admittance to a labyrinthine suite of rooms in which the region’s history was chronologically laid out from the prehistoric to the post-war periods.

Far from being overlooked, the most barbaric era was covered extensively. Photographs showed mass rallies outside the town hall, bedecked in the odious red-and-black regalia. Relics of the former Jewish community — religious objects, Torah curtains, items from destroyed synagogues — filled two rooms.

Housed in a former brewery once owned by a Jewish family, the town museum in Alsfeld contains a Torah ark — rescued, the local guide explained, from a torched synagogue the day after Kristallnacht. I offered to translate the Hebrew inscription: Yodea Leifnei Me Attah Omeyd, Know Before Whom You Are Standing. Later, seeing my interest, the guide took me to a nearby 19th-century Jewish cemetery, which he and others have labored to restore.

In Marburg, the remains of a medieval synagogue were unearthed three years ago during the routine excavation of a former parking lot. In use from about 1250 to 1450, the building was evidently rectangular with a central sexpartite vault; one of the recovered vaults features a keystone carved with a star of David. “This,” a local guide exclaimed proudly, pointing into the rectangular pit, “is by far the most exciting excavation in Marburg.”

Remnants of only about a dozen medieval synagogues of that size have been found in Central Europe, according to Ulrich Klein, an official connected with the dig through the Freies Institut fur Bauferschung und Dokumentation. “The new excavated building in Marburg is one more important example,” he said.

It is also an important example of how modern Germany is doing all it can not to forget its history and to recover its Jewish history in particular.

Guidebook recommendation: Despite the newsprint-quality paper and a lack of color pages, The Rough Guide to Germany ($23.99) provides about the most extensive maps and information available, including details on accommodation, restaurants, nightlife and special-interest activities. ♦

© 2001

Fairy Tale Roads II: In the footsteps of the Pied Piper

Our guide is sporting a multicoloured cape, tunic and leotards, a coxcomb hat adorned with ostrich feathers, and elongated orange leather shoes featuring baroque curlicues extending beyond the toes. Anywhere else, he would be locked up as a madman, but here in the picturesque village of Hameln (pronounced Ham-el-in) Germany, he is instantly recognizable as the Pied Piper of medieval lore. As he walks through laneways and streets, he plays occasional snippets of medieval ditties on a clarinet. Our group of seven follows as if in trance.

Our guide is sporting a multicoloured cape, tunic and leotards, a coxcomb hat adorned with ostrich feathers, and elongated orange leather shoes featuring baroque curlicues extending beyond the toes. Anywhere else, he would be locked up as a madman, but here in the picturesque village of Hameln (pronounced Ham-el-in) Germany, he is instantly recognizable as the Pied Piper of medieval lore. As he walks through laneways and streets, he plays occasional snippets of medieval ditties on a clarinet. Our group of seven follows as if in trance.

We pass a schoolyard and the Pied Piper pipes a nursery tune that brings most of the children to the fence, their eyes wide in happy amazement. “Out of every ten children I meet, about two children run,” he admits in perfect American English. “It’s because some parents tell their children, ‘If you’re not good today, the Pied Piper will get you.'”

As we stroll through this beautifully restored town on the Weser River, the Piper points out distinctive buildings in the Weser Renaissance style, with their projecting bay windows and handsomely decorated gables. Dating from the 16th century, many of these half-timbered houses feature grotesque faces meant to scare demons away. But it is the Piper legend, not the exuberant architecture, that draws multitudes of tourists from around the world.

The Japanese especially are fascinated with this evocative tale of the stranger who came to Hameln in 1284 and lured the local rats into the river with his flute. After the burghers refused to pay him as promised, the Piper piped again, this time luring 130 children into a cave in a nearby mountain, in which they disappeared forever. “The story is as popular in Japan as it is in Germany, because it fits into the Japanese ethnic of being an honest person and being trustworthy, as in the stories of the Samurai,” says the Piper.

His sad surreal medieval melody draws us along. Here is the Ratcatcher’s House, with an inscription on the wall documenting the legend. Further on, at Neue Marketstrasse 3, he points out the Jewish House, where 14 local Jewish families were rounded up before being deported to Theresienstadt in 1943: victims of an infinitely more malevolent piper.

His sad surreal medieval melody draws us along. Here is the Ratcatcher’s House, with an inscription on the wall documenting the legend. Further on, at Neue Marketstrasse 3, he points out the Jewish House, where 14 local Jewish families were rounded up before being deported to Theresienstadt in 1943: victims of an infinitely more malevolent piper.

Although Hameln is a major stop on northern Germany’s Fairy Tale Road, the story of the Pied Piper is not a fairy tale but a legend steeped partly in historical fact. Details of the tragic exodus from town were preserved in a medieval church window, which specified the number of people (130) and a date around June 25, 1284. “The part about the rats was later added to the story and has nothing whatsoever to do with the loss of the children.”

According to one theory, Hameln’s young people were lured away to build new villages in the east. But the Piper declares this theory weak. “Certainly someone would have come back or written a letter. The world wasn’t so large back then. There’s an element of tragedy in the story that this theory doesn’t address.”

A local scholar Gernot Husam has begun to assert that the town’s young people “were the victims of a bit of ethnic cleansing,” the Piper reports. Supposedly, a group of young people still clung to the old pre-Christian German religion, otherwise known as the Teutonic or Atlantean religion; they left town to celebrate the summer solstice in a religious festival — “a witches’ dance” — in a nearby mountain. “Many early Christians were dedicated to stamping out the old religion. Since these festivals were sometimes held underground in a labyrinth or cave, they might have forced a cave-in.”

The highest mountain visible from Hameln, the Oberburg, is 15 km away; its slopes contain many relics of the old religion, and the sun rises from behind it in June. A sinkhole, the Devil’s Hole, also contains early Christians icons, but it remains unexcavated. These details, more fully expounded in Husam’s 1990 book Copper Brugge, have all but convinced the town’s modern Pied Piper that “a bit of ethnic cleansing” occurred here 712 years ago.

Our group made numerous other stops along the Fairy Tale Road — Hamburg, Bremen, Gottingen, Marburg, Alsfeld — seeing many sites pertaining to such Grimm brothers’ fairy tales as the Bremen Town Musicians, the Goose Girl, and Sleeping Beauty. But Hameln’s sad tale, so ancient and yet so redolent of modern times, seemed to affect us more than any other. ♦

© 2001

MEDIEVAL SYNAGOGUE FOUND IN GERMAN TOWN

The remains of a medieval synagogue, including a keystone engraved with a Jewish star and a niche for the holy ark, have been unearthed in Marburg, a picturesque town of narrow streets and centuries‑old half‑timbered buildings in the central German province of Hesse.

The remains of a medieval synagogue, including a keystone engraved with a Jewish star and a niche for the holy ark, have been unearthed in Marburg, a picturesque town of narrow streets and centuries‑old half‑timbered buildings in the central German province of Hesse.

The find, which was made during a routine dig to place an underground transformer beneath a parking lot, has excited but not entirely surprised municipal officials. Old town records indicate that a synagogue had stood somewhere in the area, along the street that had been known until 1933 as the Judengasse or Jews Lane, at the northern end of the Marburg market place.

The rectangular building once featured a vaulted ceiling with a sexpartite vault, the corner pillars of which are still standing. A niche in the eastern wall was likely the former Aron Hakodesh or holy ark, and a smaller annex connected to the main hall by a slit window was likely a women’s area.

There really isn’t that much to see at the site. One looks down into an open pit lined by the massive stone blocks that were part of the synagogue’s 14th‑century walls. The building once had a sandstone floor and archaeologists have determined that it bore architectural similarities to local buildings constructed by Christians in the same period.

The oldest part of the structure dates from the 12th century, but the distinctively‑ribbed ceiling vaults and the Star of David keystone were apparently added after 1250 CE, according to Prof. Ulrich Klein, an official with the Freies Institut fur Bauferschung und Dokumentation, a local private authority charged with studying the ruin.

The oldest part of the structure dates from the 12th century, but the distinctively‑ribbed ceiling vaults and the Star of David keystone were apparently added after 1250 CE, according to Prof. Ulrich Klein, an official with the Freies Institut fur Bauferschung und Dokumentation, a local private authority charged with studying the ruin.

The building was partially destroyed in a town fire in 1319, Klein says, then rebuilt to a height of nearly four metres, corresponding to the height of the present excavated walls.

“Today we know of only about a dozen surviving medieval synagogues of that volume in Central Europe,” he says. “The newly‑excavated building in Marburg is one more important example.”

Historical sources indicate that Marburg’s Jewish community was annihilated during the Black Death persecutions of 1348 and 1349. Some Jews, however, returned to the town by 1364, and the medieval Jewry thrived for nearly a century thereafter; the town boasted some rich Jewish tradesmen.

About 1452, however, the Jews were again expelled and the synagogue damaged. Over time, the shell of the building was blocked with earth and forgotten until its rediscovery.

A Jewish community again took root in Marburg after 1532, but remained relatively small for several centuries, reaching a peak of 512 people only in 1905. A large domed synagogue built in 1897 was destroyed during Kristallnacht.

City officials have shelved plans to bury an electrical transformer beneath the parking lot. Instead, they intend to build a glass roof to protect the excavation and perhaps mark it with a descriptive plaque. ♦

© 2001