The excellent production of The Merchant of Venice, now in performance at the Stratford Festival, does not diminish the fact that this is one of Shakespeare’s more problematic and star-crossed plays.

The excellent production of The Merchant of Venice, now in performance at the Stratford Festival, does not diminish the fact that this is one of Shakespeare’s more problematic and star-crossed plays.

The most important thing to bear in mind when seeing this play is that Shakespeare had likely never seen a Jew when he wrote it about 1605. The Jews had been expelled from England in 1290 and were not officially permitted to return until 1648 or thereabouts.

Review of a production of The Merchant of Venice at the Stratford Festival, 1995

Nonetheless, Britain’s Bard had certainly heard of Rodrigo Lopez, the Sephardic Jew who had served as Queen Elizabeth’s personal physician. Several years before Shakespeare invented the rapacious and rancorous Shylock, Lopez — an Elizabethan Dreyfuss — was falsely convicted of treason and executed. Some years earlier, Shakespeare might also have heard of Joachim Gaunz, a mining expert from Prague who had let slip a few words of Hebrew while working in Bristol, for which he was branded as a Jew and deported.

Shakespeare also knew of Christopher Marlowe, the contemporaneous playwright whose earlier caricature of a Jew in The Jew of Malta, according to literary critic A.M. Klein, was “a monster by the name of Barabbas (note the reprehensible reference) who incarnated all the vices then known to civilization.” Like Barabbas, Shylock is malevolent and demonic, and seems to lack even a single redemptive quality.

While Shakespeare permits his odious money-lender to plead for sympathy with the famous “Hath a Jew not … ” soliloquoy, it is largely ineffective. Cruelly, Shylock wants to extract a pound of flesh from the merchant Antonio, who has defaulted on a loan after his ships were lost at sea. In his single-minded mania for revenge, Shylock seems a vile economic counterpart to the Jews of the medieval stereotype whose recipe for matzah supposedly calls for the blood of Christian babies.

Just as Shakespeare had likely never encountered a Jew, he had never set foot in Italy, and knew little of the ways of Venetian shipping merchants who had been insuring their cargoes for generations. But he well understood the popular prejudices of Elizabethan audiences and craftily exploited their endemic anti-semitism to increase the box-office appeal of his plays. Evidently, it mattered not that usury was as commonplace in Italy then as it was in England, where the standard legal rate of interest was 10 per cent.

The Merchant of Venice was written hurriedly to meet popular demand, without a thought to posterity. Were it written by anyone else, Shylock would be as little known today as Marlowe’s Jewish monster or the equally vile stereotypes invoked centuries earlier by Geoffrey Chaucer.

The current Stratford production alludes subtly through costume and mannerisms to fascist Italy in the 1930s, but otherwise allows playgoers to make of Shylock what they will. The program offers no preparatory comment or tempering advice: audience members are presumed to be wise enough to know anti-semitism when they see it.

Is The Merchant of Venice a play best left on the shelf? Marti Maraden, director of the current production, told Eye On Arts that this question has been debated at length at Stratford, with some concluding that the play is inherently anti-semitic and others that it merely attempts to deal, rather ineptly, with the issue of anti-semitism. “My reading of the play was that it contained virulent anti-semitism but that it needn’t be anti-semitic if we went about it the right way,” she said.

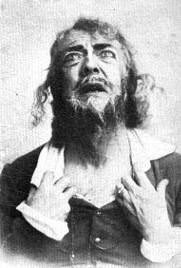

“Since Shylock is the most sensitive role, I thought that the best thing I could do was to cast the best actor I know in the part, so it went to Douglas Rain. I knew that he would bring out the humanity of Shylock, the good as well as the bad.”

Did Rain succeed in doing so? Methinks not, but the fault lies less in any member of the fine cast than in the poisoned inkwell in which Shakespeare dipped his otherwise benevolent and mighty pen. If you’ve a mind to do so, go judge for yourself. ♦

© 1995