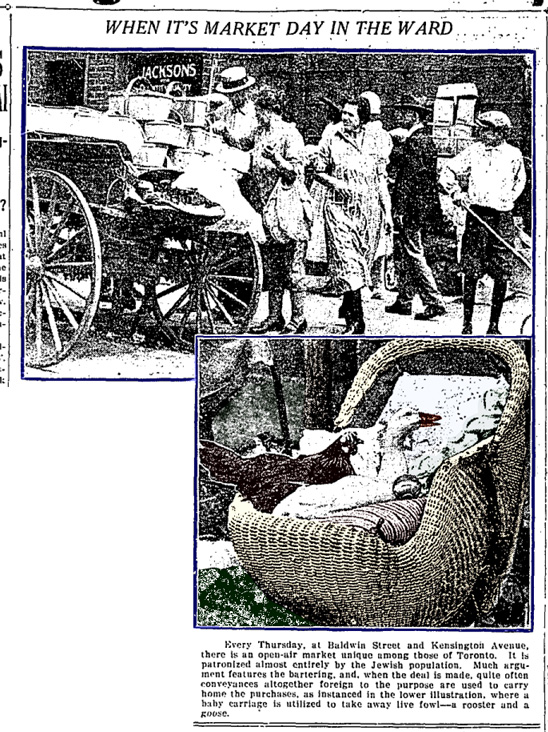

Note: This is an early and very colourfully written article about what would become a city institution, Kensington Market. It is described as being in “the Ward,” but technically it lies outside of the Ward’s unofficial western boundary of University Avenue or McCaul Street; what the author really meant to say was that it was in the city’s Jewish district. ◊

From the Globe and Mail, July 17, 1925

What news on the Rialto? Nothing, at first, but noise — jangling, raucous, unforgettable noise.

What news on the Rialto? Nothing, at first, but noise — jangling, raucous, unforgettable noise.

The seductive call of the huckster, the discord of hand bells and motor horns, the high-pitched wail of outraged housewives as they face the fact of 60 cents for 11 quarts of cherries — sour ones, too — the wrangle of half a dozen determined females as they struggle to the death for that last luscious watermelon, and, like the unceasing, rhythmic beat of the drum in a Chinese drama, the steady quack of solemn ducks and the occasional indignant outbursts of an otherwise immaculately mannered hen — of such is the merry din that breaks upon the startled cars of the visitor to the Thursday market in Kensington Place.

There is no other market in or out of Toronto quite like this Jewish curb market. It has an individuality unknown in the sober purlieus of the St. Lawrence or suburban markets. It has colour; it has gesture; it has art. There the skill of the trader, usually submerged under custom and swamped by advertised prices, has been polished by much usage until it dazzles the innocent with its lustre.

There you must have all your wits about you. If you have them, the money is unimportant. You enter into the game with all the native relish of finesse. Somebody’s going to drive a bargain. Is that somebody you?

Sixty cents for a basket of cherries? “Oi! Oi!” “Parbleu! Ouch!” — or whatever the translation is — are you to pay 60 cents for cherries, when Rosy’s been out of work and Sady got only $13.75 at the tailor shop?

Now is the time to impress the slouch=hatted huckster. You hit not below the belt, but in a “more tenderer spot,” as Tony Weller used to say. You wring his heart with tales of woe and poverty and hunger. Look, you show him you speak truth. You bring out two quarters, pathetically stowed away in the pocket of your check housedress. That is all you have, and anyway the cherries are sour.

They Are Too Sour! Too Sour!

“Oi! Oi! What sugar they will need! And after all, you have only 50 cents. And anyway, they are too dear, too dear, and anyhow they are so sour, so sour. You make a noise like dearness and face like sourness, and you flash the two quarters in front of his face. Now is the accepted time.

If you are an adept at the game, if the face and the gesticulations have been sufficiently well practiced, you will carry off the basket triumphant. If you are but fair and the huckster not so innocent, you will compromise at 55 cents. If you are absolutely without talent for stratagem — well, in that case, you should never go to the Kensington market.

Viewed from Dundas Street at about 2 o’clock of a quiet Thursday afternoon, there is little about Kensington Avenue to distinguish it from the other neighbouring thoroughfares. Carts and dilapidated motors, to be sure, and a plethora of children — but these are not especially the earmarks of a market.

Proceeding, you see curious collections of parlour-window ornaments — beside a yellow marble clock stands a crate of cackling hens, or a display of second-hand china; you push your way through clusters of ancient dames, hardly visible beneath burdens of concertina-like loaves and babies and wriggling chickens; you scrape your shins against go-carts overflowing with carrots and carp, and presto! Before you know it, you are in Kensington Place, the Rialto of the Ward.

Sight, Smell and Taste.

Sight and smell are not the only means to good judgment on this market. The Jewish chatelaine know the wisdom of taste, and to the last raw carrot she exercises her discriminating prerogative of taste. Potatoes and cocoanuts are the only things outside her reach. She promenades up and down between the lines of carts, sampling a handful of currants here, a berry there, and a few green peas farther on.

The taste tells, and only when it is sufficiently convincing does she return for closer investigation. Where is the skeptic that will not agree it was an ancestor of this shrewd, wrinkled Jewess, comical in her marked-down gingham dress, of whom it was written: “She looketh well to the ways of her household, and eatest not the bread of idleness?” ♦